Feb 3, 2026

You have the vial in your hand. The peptide powder sits inside, delicate and expensive. And now you are staring at a bottle of bacteriostatic water, wondering exactly how much to draw up. Too much water and your doses become impractical, requiring volumes that overflow your syringe. Too little and you cannot measure accurately, turning every injection into a guessing game where a tiny error means a massive dosing mistake.

This is the moment where most researchers get stuck. Not because reconstitution is complicated, but because nobody explains the actual math clearly. The forums say 1 mL. Some guides say 2 mL. Others recommend 5 mL. Which is correct? The answer depends on your vial size, your target dose, and your syringe type, and once you understand the simple formula behind it all, you will never second-guess this step again.

This guide breaks down the exact amount of bacteriostatic water to add for every common vial size. We cover the core concentration formula, practical charts for 2 mg through 30 mg vials, syringe conversion tables, and the mistakes that waste peptides and ruin results. Whether you are working with BPC-157, TB-500, ipamorelin, or any other research peptide, the principles remain identical. SeekPeptides members rely on these exact calculations daily through our reconstitution calculator, and now you will have the knowledge to do the same.

The core formula you need to know

Every calculation starts from one simple equation. Peptide amount in milligrams divided by water volume in milliliters equals concentration in milligrams per milliliter. That is the entire foundation. Once you know your concentration, you can calculate exactly how much liquid to draw for any dose.

Here is the formula written out:

Concentration (mg/mL) = Peptide Amount (mg) / Water Volume (mL)

And to find how much to draw per dose:

Volume to Draw (mL) = Desired Dose (mg) / Concentration (mg/mL)

Simple. But the implications matter enormously.

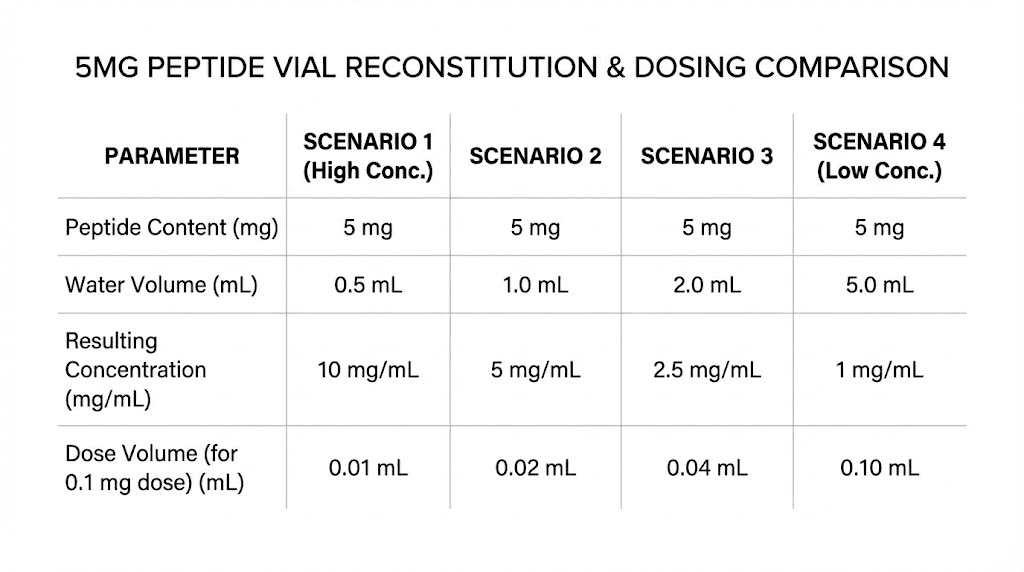

If you have a 5 mg vial and add 1 mL of water, your concentration is 5 mg/mL. Each 0.1 mL (10 units on an insulin syringe) contains 500 mcg. That is a very concentrated solution. Fine for larger doses, but problematic if you need 100 mcg, because 100 mcg would be just 0.02 mL, or 2 units on the syringe. Reading 2 units accurately on a standard syringe is nearly impossible.

Now take that same 5 mg vial and add 2 mL of water. Concentration drops to 2.5 mg/mL. Your 100 mcg dose becomes 0.04 mL, or 4 units. Still tight but more workable. Add 5 mL and the concentration becomes 1 mg/mL, making 100 mcg equal to 0.1 mL, or a clean 10 units. Easy to read. Easy to measure. Easy to get right.

The tradeoff? More water means more volume per dose, which means larger injections. And it means the vial runs out faster in terms of available draws. With 5 mL of water in a small vial, you may only get 40-50 draws before the vial is empty. With 1 mL, you might get 10-20 draws with smaller volumes each time.

Neither approach is wrong. The right choice depends on your specific dosing protocol, your syringe size, and how many doses you need per vial. We will cover the optimal choices for every common vial size in the sections below.

Understanding insulin syringes and unit conversions

Before diving into vial-specific charts, you need to understand how insulin syringes work. This is where most confusion starts, because syringes measure in "units" while peptide doses are in micrograms or milligrams.

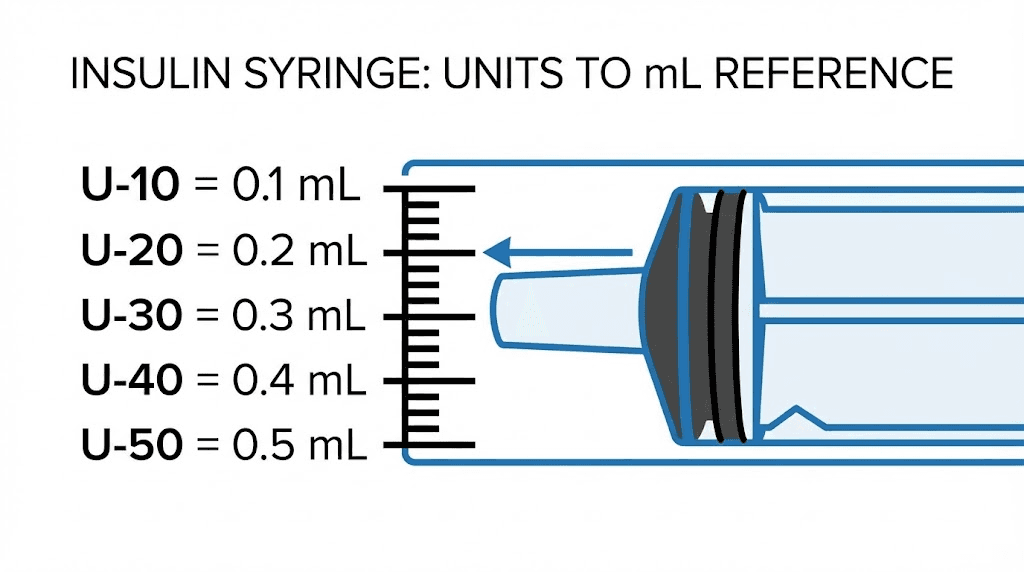

A standard U-100 insulin syringe has 100 units per 1 mL. That means:

1 unit = 0.01 mL

10 units = 0.1 mL

50 units = 0.5 mL

100 units = 1.0 mL

The "U-100" designation refers to the insulin concentration the syringe was designed for, not anything about peptides. For peptide research, you simply use the volume markings. Each tick mark on a 1 mL syringe represents 1 unit, which is 0.01 mL.

Syringes come in three main sizes. The 0.3 mL syringe holds 30 units and offers the finest precision for small doses. The 0.5 mL syringe holds 50 units and works well for moderate volumes. The 1.0 mL syringe holds 100 units and handles larger draws but has slightly less precision at the small end.

For most peptide protocols, the 0.5 mL or 1.0 mL syringe works best. If your calculated dose falls below 5 units (0.05 mL), you either need a 0.3 mL syringe with finer markings or you should add more bacteriostatic water to reduce the concentration.

Here is the critical conversion to memorize. Once you know your peptide concentration in mg/mL, multiply by 0.01 to find how many milligrams are in each syringe unit. Or to think about it differently, if your concentration is 5 mg/mL, then each 1 unit (0.01 mL) contains 50 mcg. Each 10 units (0.1 mL) contains 500 mcg.

This relationship between water volume, concentration, and syringe units is what the SeekPeptides peptide calculator computes automatically. But understanding the math yourself means you can verify your calculations and catch errors before they happen. That matters when you are working with compounds that cost significant money per vial and where dosing precision determines whether your research succeeds or fails.

How much water to add to a 2 mg vial

Two milligram vials are common for potent peptides where doses are measured in low micrograms. Think compounds like PT-141, certain bioregulator peptides, or other highly concentrated research compounds.

With only 2 mg total, you need to be careful about dilution. Too much water and you will have an extremely dilute solution where huge volumes are needed per dose. The sweet spot for 2 mg vials is typically 0.5 mL to 1 mL of bacteriostatic water.

Water Added | Concentration | 100 mcg Dose | 200 mcg Dose | 500 mcg Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0.5 mL | 4 mg/mL | 2.5 units (0.025 mL) | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 12.5 units (0.125 mL) |

1 mL | 2 mg/mL | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 10 units (0.1 mL) | 25 units (0.25 mL) |

2 mL | 1 mg/mL | 10 units (0.1 mL) | 20 units (0.2 mL) | 50 units (0.5 mL) |

Best choice for 2 mg vials: 1 mL of bacteriostatic water gives you a clean 2 mg/mL concentration. Most common doses fall in the easy-to-read range of 5-25 units. If your protocol calls for very small doses (under 50 mcg), consider 2 mL instead to make measurements more practical.

One important note about small vials. With only 2 mg of peptide and 1 mL of water, you have a limited number of draws before the vial is depleted. At 200 mcg per dose, that is only 10 doses per vial. Plan your peptide cycle accordingly and have additional vials ready.

How much water to add to a 5 mg vial

Five milligram vials are the most common format in peptide research. BPC-157, TB-500, sermorelin, hexarelin, and dozens of other peptides ship in 5 mg vials. This is the format you will encounter most often, and getting the water volume right here matters most.

The optimal amount depends on your typical dose range.

Water Added | Concentration | 100 mcg Dose | 250 mcg Dose | 500 mcg Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 mL | 5 mg/mL | 2 units (0.02 mL) | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 10 units (0.1 mL) |

2 mL | 2.5 mg/mL | 4 units (0.04 mL) | 10 units (0.1 mL) | 20 units (0.2 mL) |

2.5 mL | 2 mg/mL | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 12.5 units (0.125 mL) | 25 units (0.25 mL) |

5 mL | 1 mg/mL | 10 units (0.1 mL) | 25 units (0.25 mL) | 50 units (0.5 mL) |

Best choice for most 5 mg protocols: 2 mL of bacteriostatic water is the sweet spot for researchers taking 200-500 mcg doses. It creates a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL where common doses land on clean, easy-to-read syringe markings. A 250 mcg dose is exactly 10 units. A 500 mcg dose is exactly 20 units. No guessing, no squinting at tiny marks.

For lower doses (100-200 mcg), 2.5 mL works well, giving you a 2 mg/mL concentration where 100 mcg is a clean 5 units.

For the easiest math (at the cost of larger injection volumes), 5 mL creates a simple 1 mg/mL solution. Every 0.1 mL (10 units) equals exactly 100 mcg. The downside is that a 500 mcg dose requires drawing 50 units (0.5 mL), which is a larger injection volume.

With 2 mL of water in a 5 mg vial and a 250 mcg twice-daily protocol, you get 10 doses, or 5 days of research. That means going through roughly 6 vials per month. Understanding this math helps you plan procurement and manage costs effectively.

The BPC-157 dosage calculator on SeekPeptides handles these exact calculations for one of the most popular 5 mg peptides. But the math works identically for ipamorelin, CJC-1295, GHRP-6, and every other 5 mg peptide.

How much water to add to a 10 mg vial

Ten milligram vials offer more peptide per container, which means more flexibility in how you dilute. You will find 10 mg vials for peptides like BPC-157 (in higher-quantity formats), MOTS-C, epitalon, and many growth hormone secretagogues.

The extra peptide mass gives you room to choose concentrations that make dosing cleaner without running out too quickly.

Water Added | Concentration | 100 mcg Dose | 250 mcg Dose | 500 mcg Dose | 1000 mcg Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 mL | 10 mg/mL | 1 unit (0.01 mL) | 2.5 units (0.025 mL) | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 10 units (0.1 mL) |

2 mL | 5 mg/mL | 2 units (0.02 mL) | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 10 units (0.1 mL) | 20 units (0.2 mL) |

3 mL | 3.33 mg/mL | 3 units (0.03 mL) | 7.5 units (0.075 mL) | 15 units (0.15 mL) | 30 units (0.3 mL) |

5 mL | 2 mg/mL | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 12.5 units (0.125 mL) | 25 units (0.25 mL) | 50 units (0.5 mL) |

Best choice for 10 mg vials: 2 mL gives you the versatile 5 mg/mL concentration. Common doses land on clean syringe readings, and the vial lasts a reasonable number of draws. For protocols requiring 250 mcg or less, 3 mL works well since it keeps doses in the 5-10 unit range where accuracy is high.

Avoid using just 1 mL with a 10 mg vial unless your doses are 500 mcg or higher. At 10 mg/mL, a 100 mcg dose is a single unit on the syringe. One unit is 0.01 mL. The difference between pulling 1 unit and 2 units is a 100% dosing error, and at that scale, the margin for mistake is unacceptably thin.

A 10 mg vial with 2 mL of water at 500 mcg twice daily gives you 10 days of research per vial. That is roughly 3 vials per month. The economics improve compared to 5 mg vials, and the peptide cost calculator can help you compare the per-dose cost across different vial sizes and concentrations.

How much water to add to a 15 mg vial

Fifteen milligram vials are less common but appear for certain peptides, particularly some longevity compounds and higher-dose protocols. The larger peptide amount gives even more flexibility.

Water Added | Concentration | 250 mcg Dose | 500 mcg Dose | 1000 mcg Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2 mL | 7.5 mg/mL | 3.3 units (0.033 mL) | 6.7 units (0.067 mL) | 13.3 units (0.133 mL) |

3 mL | 5 mg/mL | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 10 units (0.1 mL) | 20 units (0.2 mL) |

5 mL | 3 mg/mL | 8.3 units (0.083 mL) | 16.7 units (0.167 mL) | 33.3 units (0.333 mL) |

Best choice for 15 mg vials: 3 mL creates a clean 5 mg/mL concentration. The math stays simple and doses land on practical syringe readings. At 500 mcg per dose, you get 30 doses from a single vial, which is outstanding economy.

How much water to add to a 30 mg vial

Thirty milligram vials typically contain GLP-1 receptor agonists or other peptides used at higher doses over longer periods. Peptides like retatrutide and similar weight loss compounds sometimes come in larger vials.

Water Added | Concentration | 500 mcg Dose | 1 mg Dose | 2.5 mg Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2 mL | 15 mg/mL | 3.3 units (0.033 mL) | 6.7 units (0.067 mL) | 16.7 units (0.167 mL) |

3 mL | 10 mg/mL | 5 units (0.05 mL) | 10 units (0.1 mL) | 25 units (0.25 mL) |

5 mL | 6 mg/mL | 8.3 units (0.083 mL) | 16.7 units (0.167 mL) | 41.7 units (0.417 mL) |

6 mL | 5 mg/mL | 10 units (0.1 mL) | 20 units (0.2 mL) | 50 units (0.5 mL) |

Best choice for 30 mg vials: 3 mL creates a 10 mg/mL concentration that works well for milligram-level doses. For protocols in the 1-2.5 mg range, 3 mL keeps injection volumes manageable at 10-25 units per dose. If you want the simplest math, 6 mL gives you 5 mg/mL, but that means more liquid in the vial and larger injection volumes.

GLP-1 peptides like cagrilintide and semaglutide are extremely potent at small doses, so some researchers use as little as 0.5-1 mL for these compounds. The semaglutide dosage calculator accounts for these specific reconstitution needs.

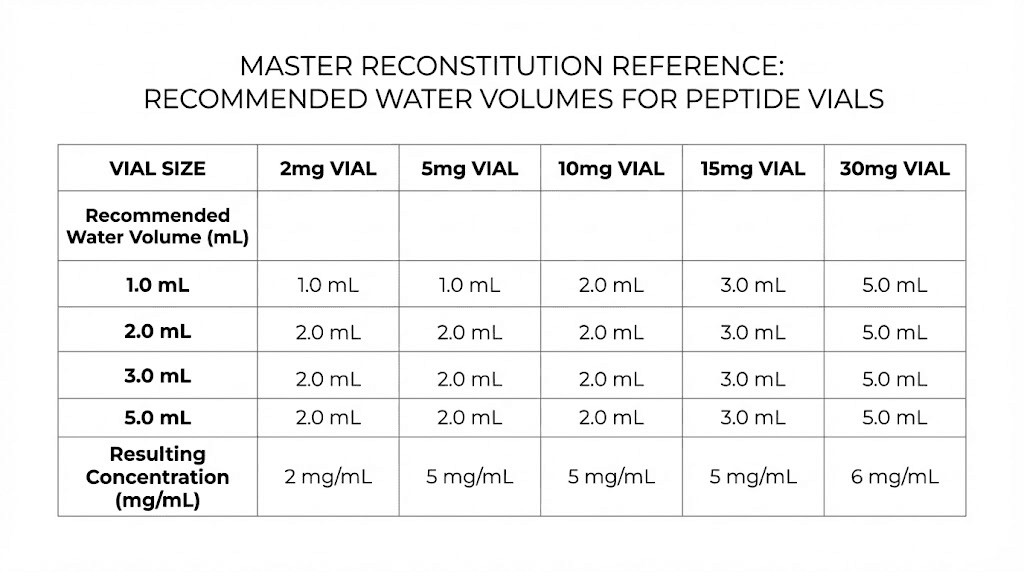

Quick reference: recommended water volumes by vial size

Here is the summary table. Pin this somewhere accessible in your research space.

Vial Size | Recommended Water | Concentration | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

2 mg | 1 mL | 2 mg/mL | Low-dose protocols (50-500 mcg) |

5 mg | 2 mL | 2.5 mg/mL | Standard protocols (200-500 mcg) |

10 mg | 2 mL | 5 mg/mL | Medium-dose protocols (250-1000 mcg) |

15 mg | 3 mL | 5 mg/mL | Standard to high-dose protocols |

30 mg | 3 mL | 10 mg/mL | High-dose protocols (1-5 mg) |

These are starting recommendations. Adjust based on your specific protocol needs, syringe size, and comfort with injection volumes. The goal is always a concentration where your typical dose falls between 5 and 50 units on the syringe, the zone where measurement accuracy is highest.

Why the amount of water matters more than you think

Getting the water volume wrong does not just make dosing inconvenient. It can actively undermine your entire research protocol. Here is why precision matters at every step.

Over-dilution problems

Adding too much water creates a solution so dilute that practical dosing becomes difficult or impossible. Imagine adding 10 mL to a 2 mg vial. Your concentration is 0.2 mg/mL. A 250 mcg dose requires 1.25 mL, which exceeds the capacity of a standard 1 mL insulin syringe. You would need to draw twice, introducing additional error and contamination risk with each needle puncture.

Over-dilution also means each dose draws a larger volume from the vial, depleting it faster. With 10 mL of water in a 2 mg vial, you might only get 4-5 usable doses before the liquid level drops too low to draw from effectively.

Excessive dilution can also affect peptide stability. At very low concentrations, peptides are more prone to adsorbing onto the glass walls of the vial, effectively reducing the amount available in solution over time. This surface adsorption effect is more pronounced with lower peptide concentrations.

Under-dilution problems

Too little water creates the opposite problem. The solution is so concentrated that tiny measurement errors translate to massive dosing discrepancies.

Consider a 10 mg vial with just 0.5 mL of water. Concentration is 20 mg/mL. A 250 mcg dose is just 1.25 units on the syringe. The difference between 1 unit and 2 units represents a 100% change in dose, from 200 mcg to 400 mcg. At that precision level, even a slight tremor in your hand or a small air bubble changes your dose significantly.

Under-dilution also concentrates any contaminants or degradation products. If the peptide has partially degraded, a concentrated solution delivers a proportionally larger amount of those degradation products per dose.

The stability sweet spot

Research on peptide stability suggests that moderate concentrations, typically in the 1-10 mg/mL range, offer the best balance between stability and practicality. This range minimizes surface adsorption losses while keeping injection volumes reasonable and measurement errors acceptable.

The bacteriostatic water itself helps with stability. The 0.9% benzyl alcohol prevents bacterial growth for up to 28 days after first puncture, which is why bacteriostatic water is strongly preferred over sterile water for multi-dose peptide vials. Sterile water lacks this preservative and must be used within 24 hours of opening, making it impractical for protocols lasting days or weeks.

For a deep dive into the differences, see our complete guide on which water to mix with peptides.

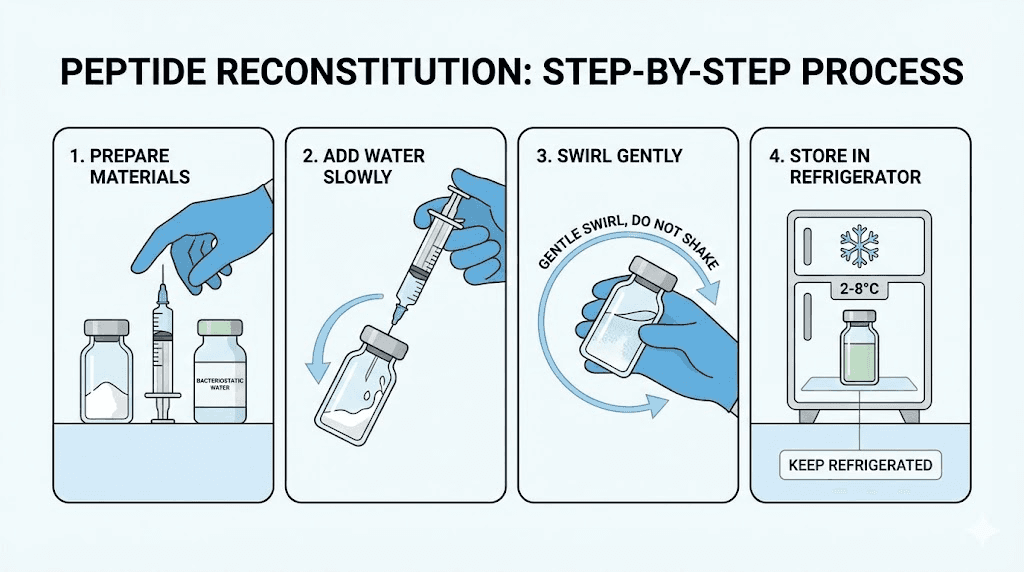

Step-by-step reconstitution process

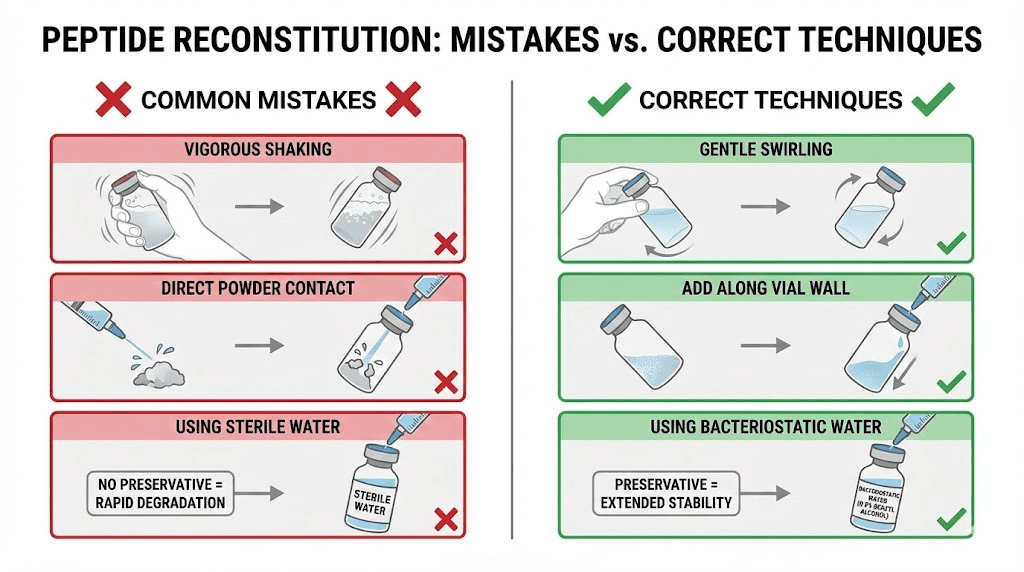

Knowing how much water to add is only half the equation. How you add it matters just as much. Poor technique destroys peptides regardless of perfect calculations.

What you need before starting

Your peptide vial (lyophilized powder)

Bacteriostatic water (USP grade, 0.9% benzyl alcohol)

Sterile insulin syringes (1 mL U-100 for most applications)

Alcohol swabs (70% isopropyl)

Clean, flat workspace

Label or marker for dating the vial

Step 1: Bring everything to room temperature

If your peptide vial was stored in the freezer or refrigerator, let it sit at room temperature for 15-20 minutes before reconstituting. Cold peptide powder and cold water do not mix well. Temperature shock can cause precipitation, where the peptide crashes out of solution and forms visible particles that indicate permanent damage.

The bacteriostatic water should also be at room temperature. Injecting cold water onto the peptide powder can create thermal stress that degrades sensitive amino acid sequences. Patience here saves money and preserves potency.

Step 2: Sanitize everything

Wipe the rubber stopper on both the peptide vial and the bacteriostatic water vial with alcohol swabs. Press firmly and wipe for at least 10-15 seconds per vial. This is not optional. Contamination at this stage can introduce bacteria that the benzyl alcohol alone may not fully control, especially with repeated access over weeks.

Wash your hands thoroughly or wear disposable gloves. The safety protocols around sterile technique exist because infections from contaminated injections are a real risk, not a theoretical one.

Step 3: Draw the bacteriostatic water

Using a fresh, sterile syringe, insert the needle through the rubber stopper of the bacteriostatic water vial. Turn the vial upside down. Pull back the plunger to draw your predetermined amount. If you calculated 2 mL for a 5 mg vial, draw exactly to the 2 mL mark (or use multiple draws with a 1 mL syringe).

Check for air bubbles. Tap the syringe gently to move bubbles to the top, then push the plunger slightly to expel them. Air bubbles take up volume that should be water, leading to under-dosing.

Step 4: Add water to the peptide vial (the critical step)

This is where technique matters most. Do NOT inject the water directly onto the peptide powder. The force of water hitting the delicate lyophilized cake can shear peptide bonds and denature the compound.

Instead, angle the needle so it touches the inside wall of the vial. Slowly depress the plunger, letting the water trickle down the glass wall. This gentle approach prevents foaming, which creates air-liquid interfaces where peptides denature and aggregate irreversibly.

Go slowly. A steady, controlled stream over 15-30 seconds is ideal. Rushing this step is one of the most common mistakes beginners make.

Step 5: Let it dissolve naturally

After adding the water, set the vial down. Do not shake it. Shaking creates foam and mechanical stress that breaks peptide chains. Some sources recommend gentle swirling, and that is acceptable, but the best approach is often just patience.

Most peptides dissolve completely within 5-10 minutes at room temperature. Some take longer, up to 30 minutes in rare cases. If you see undissolved particles after 30 minutes, try very gentle rolling of the vial between your palms. Never vortex or vigorously shake.

The resulting solution should be clear and colorless. Any cloudiness, discoloration, or visible particles suggest a problem, potentially contamination, degradation, or improper reconstitution. Do not use a cloudy solution.

Step 6: Label and store

Write the date, peptide name, concentration, and amount of water added on the vial. This seems trivial but becomes critical when you have multiple vials in the refrigerator.

Store the reconstituted peptide at 2-8 degrees Celsius (standard refrigerator temperature). Most peptides reconstituted in bacteriostatic water remain stable for 3-4 weeks at this temperature. For longer storage, some researchers freeze aliquots at -20 degrees Celsius, though repeated freeze-thaw cycles degrade peptides. Our guide on storing peptides after reconstitution covers the full details.

Peptide-specific water recommendations

While the formula works universally, certain peptides have specific considerations that affect the optimal water volume.

BPC-157 (5 mg or 10 mg vials)

BPC-157 is one of the most commonly reconstituted peptides. Standard protocols call for 200-300 mcg twice daily, typically administered subcutaneously near the area of interest.

For a 5 mg vial, 2 mL of bacteriostatic water creates a 2.5 mg/mL solution. A 250 mcg dose equals exactly 10 units on the syringe. Clean, simple, hard to get wrong. For a 10 mg vial, 2 mL gives you 5 mg/mL, where 250 mcg is 5 units. Still workable but tighter. If you want more room, 4 mL for a 10 mg vial gives 2.5 mg/mL and the same easy 10-unit doses.

BPC-157 is stable in bacteriostatic water and dissolves readily at room temperature. No special considerations beyond standard technique. Use the BPC-157 calculator for automatic calculations.

TB-500 (5 mg vials)

TB-500 protocols often use higher doses, typically 2-2.5 mg twice weekly during loading phases. For a 5 mg vial, 1 mL of water gives 5 mg/mL. A 2.5 mg dose equals 50 units (0.5 mL), which fills half a 1 mL syringe. That works but is a larger injection.

Alternatively, 2 mL gives 2.5 mg/mL, making a 2.5 mg dose equal to 1 mL, the full syringe. For TB-500, many researchers prefer 1 mL of water to keep injection volumes smaller, accepting the need for careful measurement. The TB-500 calculator handles these specific calculations.

TB-500 dissolves easily and is stable in bacteriostatic water. It can also be combined with BPC-157 in the same syringe for convenience, though they should be reconstituted in separate vials.

Growth hormone secretagogues (ipamorelin, CJC-1295, GHRP-6)

Peptides like ipamorelin, CJC-1295, and GHRP-6 typically come in 2 mg or 5 mg vials with protocols calling for 100-300 mcg doses. For 5 mg vials, 2 mL of water works well. For the popular sermorelin-ipamorelin blend, follow the specific reconstitution instructions provided with the blend since the total peptide mass may differ.

CJC-1295 with DAC has a longer half-life and is typically dosed once or twice weekly at higher amounts (1-2 mg). For these protocols, less water (1 mL) keeps injection volumes manageable. The CJC-1295 calculator accounts for both DAC and non-DAC variants.

GLP-1 peptides (semaglutide, tirzepatide, retatrutide)

Semaglutide, tirzepatide, and retatrutide are highly potent GLP-1 compounds. Doses start very low (0.25 mg weekly for semaglutide) and titrate up slowly. These peptides require special attention.

For a 5 mg semaglutide vial, 0.5-1 mL of bacteriostatic water creates a concentrated solution appropriate for the tiny weekly doses. With 0.5 mL, concentration is 10 mg/mL, and a 0.25 mg dose is 2.5 units. With 1 mL, concentration is 5 mg/mL, and 0.25 mg is 5 units, which is slightly easier to measure.

Important note: Some GLP-1 analogs may be sensitive to benzyl alcohol. Some manufacturers recommend sterile saline instead of bacteriostatic water for these specific compounds. Always check the manufacturer recommendations for your specific GLP-1 peptide.

Peptides that should NOT use bacteriostatic water

Not all peptides are compatible with bacteriostatic water. The benzyl alcohol preservative can degrade certain sensitive compounds. These include:

Oxytocin, which degrades when exposed to benzyl alcohol

Desmopressin and vasopressin, both sensitive to the preservative

hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), which should use sterile water or saline

IGF-1 LR3 and IGF-1 DES, which require 0.6% acetic acid solution instead

NAD+, which also degrades in bacteriostatic water within 24-48 hours

For these compounds, use preservative-free sterile water or the solvent specified by the manufacturer. The key indicator is that if your peptide solution becomes cloudy or develops particles within hours of reconstitution, benzyl alcohol incompatibility may be the cause.

If you are unsure whether your specific peptide works with bacteriostatic water, check the manufacturer datasheet or consult the complete peptide reference list for compatibility information.

Common mistakes that waste peptides and money

Knowing the right amount to add is essential. But avoiding these mistakes is equally important. Each one can reduce potency, introduce contamination, or render your entire vial useless.

Mistake 1: Shaking the vial after adding water

This is the single most common reconstitution error. Shaking creates foam, and foam means air-liquid interfaces where peptide molecules unfold and aggregate. Once aggregated, those molecules are permanently denatured. They will not fold back into their active configuration.

The result is a vial that looks fine but contains less active peptide than you think. Your calculated dose is accurate based on what went into the vial, but the actual active compound is lower because some percentage was destroyed by shaking.

Gentle swirling or patient waiting is always the correct approach.

Mistake 2: Squirting water directly onto the powder

Directing the stream of bacteriostatic water straight down onto the lyophilized cake creates localized high concentrations and mechanical disruption. The force of impact can break peptide bonds. The powder can also splash up into the rubber stopper area where it is lost.

Always aim the water at the glass wall and let it trickle down gently. This protects the peptide structure and ensures even dissolution.

Mistake 3: Using too much or too little water without calculating

"Just add 2 mL" is advice that works for some vial sizes and fails completely for others. Two milliliters in a 2 mg vial gives you a workable 1 mg/mL. Two milliliters in a 30 mg vial gives you 15 mg/mL, which may be too concentrated for small doses.

Always run the calculation first. Know your vial size, know your target dose, and work backward to the optimal water volume. The reconstitution calculator does this in seconds.

Mistake 4: Not equalizing temperature

Taking a frozen peptide vial and immediately adding room-temperature water causes thermal shock. The rapid temperature change can precipitate the peptide, creating visible particles or invisible aggregates that reduce potency.

Let both the peptide and the bacteriostatic water reach room temperature before mixing. This takes 15-20 minutes and costs nothing but patience.

Mistake 5: Reusing syringes or not sanitizing

Every time you access a vial with a needle, you risk introducing contaminants. A used syringe carries bacteria from the previous injection site. A non-sanitized rubber stopper may harbor environmental microorganisms.

Use a fresh syringe for every draw. Swab the stopper before every needle insertion. These simple steps prevent the kind of contamination that turns a good peptide into a bacterial culture medium.

Mistake 6: Excessive stopper punctures

Each needle puncture through the rubber stopper creates a tiny channel that can allow air and contaminants inside. After 15-20 punctures, the stopper may not reseal properly, compromising the sterile environment.

Plan your draws to minimize punctures. If a vial will require more than 20 draws, consider reconstituting into a fresh sterile vial after the stopper shows visible wear. This is particularly relevant for small, frequent doses from large vials.

Mistake 7: Ignoring cloudiness or discoloration

A properly reconstituted peptide solution is clear and colorless. Period. Any change from this indicates a problem.

Cloudiness suggests precipitation, aggregation, or contamination. Yellow or brown discoloration indicates oxidation or degradation. Visible particles mean the peptide has crashed out of solution. In all cases, the safest course is to discard the vial. Using a compromised solution means unknown dosing and potential safety risks.

See our guide on peptide storage best practices for more on maintaining solution quality over time.

How long does reconstituted peptide last?

The clock starts the moment bacteriostatic water touches the peptide powder. From that point, degradation begins, slowly at first but accelerating over time.

Refrigerator storage (2-8 degrees Celsius)

Most peptides reconstituted in bacteriostatic water maintain acceptable potency for 3-4 weeks when refrigerated consistently. Some more stable peptides can last 4-6 weeks, while fragile ones may show significant degradation by week 2.

The benzyl alcohol in bacteriostatic water prevents bacterial growth for approximately 28 days after first puncture. After that, the preservative effect diminishes and contamination risk increases even with proper technique.

The practical rule: use reconstituted peptides within 28 days. If your protocol will take longer than that to use a full vial, reconstitute smaller amounts more frequently.

Freezer storage (-20 degrees Celsius)

Freezing reconstituted peptide can extend usable life to 2-4 months. However, this comes with significant caveats. The solution must be aliquoted into single-use portions before freezing. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles destroy peptides through ice crystal formation that physically tears apart molecular structures.

If you freeze, use small sterile vials or tubes. Put one dose worth of solution in each. Thaw one at a time, use it, and discard. Never refreeze a thawed aliquot.

For detailed storage timelines by peptide type, see how long reconstituted peptides last in the fridge and at room temperature.

Room temperature storage

Avoid it entirely. Reconstituted peptides degrade rapidly at room temperature. Even a few hours above 8 degrees Celsius accelerates degradation significantly. If a vial was left out overnight, the peptide may have lost meaningful potency. Conservative researchers discard any vial left at room temperature for more than 1-2 hours.

The water volume affects how many doses you get per vial

Understanding vial economics helps you plan research protocols and manage budgets. The amount of water you add does not change the total peptide in the vial, but it affects how many usable draws you can get.

Example: 5 mg vial at 250 mcg per dose

Total peptide: 5,000 mcg. At 250 mcg per dose, that is 20 doses regardless of water volume.

With 1 mL of water: Each dose is 5 units (0.05 mL). After 20 draws of 5 units each, you have used 1 mL total. Vial is empty.

With 2 mL of water: Each dose is 10 units (0.1 mL). After 20 draws of 10 units each, you have used 2 mL total. Vial is empty.

The number of doses stays the same. What changes is the volume per draw and how easy each measurement is to make accurately. More water means easier measurements but larger injection volumes. Less water means smaller injections but tighter measurements.

However, there is a practical consideration. Below approximately 0.1-0.2 mL of liquid remaining in a vial, it becomes difficult to draw with a standard insulin syringe. The needle cannot reach the last drops. This means you might lose 1-2 doses worth of peptide at the bottom of the vial regardless of your water volume.

With more water in the vial, this "dead volume" loss represents a smaller percentage of total peptide. With 1 mL of water, losing 0.1 mL at the bottom is a 10% loss. With 2 mL, the same 0.1 mL is only a 5% loss. Something to consider when choosing your water volume, especially with expensive compounds.

Using a peptide reconstitution calculator

While understanding the math is essential, using a calculator eliminates arithmetic errors that cost real money. SeekPeptides offers a free reconstitution calculator that handles all the conversions automatically.

Here is how to use it effectively.

Enter your vial size in milligrams. This is printed on the vial label. Common sizes are 2 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, and 30 mg.

Enter the amount of bacteriostatic water you plan to add in milliliters. If you are unsure, start with the recommendations from the quick reference table earlier in this guide.

Enter your desired dose in micrograms (mcg) or milligrams (mg). The calculator converts between units automatically.

The calculator outputs the exact volume to draw on your syringe, expressed in both mL and insulin syringe units. It also shows the resulting concentration, total doses per vial, and cost per dose if you input the vial price.

This is faster than manual calculation and eliminates the transcription errors that happen when converting between milligrams, micrograms, milliliters, and syringe units by hand. For specific peptides, the dedicated calculators like the general peptide calculator, BPC-157 calculator, TB-500 calculator, or HGH fragment calculator include peptide-specific dosing ranges and protocol suggestions alongside the reconstitution math.

Bacteriostatic water vs. sterile water vs. other solvents

Not all reconstitution liquids are the same. The choice of solvent affects stability, safety, and shelf life.

Bacteriostatic water

Contains 0.9% benzyl alcohol as a bacteriostatic preservative. Prevents bacterial growth for up to 28 days after first use. Safe for multi-dose vials. This is the recommended solvent for the vast majority of injectable peptides.

Store unopened at room temperature. After first use, refrigerate and discard after 28 days.

Sterile water

Pure water with no preservatives. Must be used as a single-dose preparation. Once opened, it supports bacterial growth immediately. Use only when bacteriostatic water is specifically contraindicated (the benzyl alcohol-sensitive peptides listed earlier).

For researchers who need to understand the full comparison, our article on bacteriostatic water for peptides covers the safety and compatibility details in depth.

0.6% acetic acid solution

Required for certain peptides like IGF-1 LR3, IGF-1 DES, and NAD+ that degrade in both bacteriostatic and sterile water. The mild acidity stabilizes these specific molecular structures. Do not use acetic acid for peptides that do not specifically require it.

Bacteriostatic saline (0.9% NaCl with benzyl alcohol)

Similar to bacteriostatic water but with added sodium chloride. Sometimes preferred for peptides where the saline helps maintain pH stability. Not as commonly used as plain bacteriostatic water but acceptable for most peptides.

What to never use

Tap water. Distilled water from the store. Boiled water. Water from any non-pharmaceutical source. None of these are sterile, and all will introduce contaminants that make injection dangerous. Only use USP-grade pharmaceutical solvents for peptide injection reconstitution.

How to adjust water volume for stacking protocols

Many researchers run peptide stacks, using multiple peptides simultaneously. This introduces the question of injection volume management. If you are taking three peptides twice daily, that is six injections per day, and minimizing the volume of each one becomes more important.

Strategy 1: Use less water for concentrated solutions

When running stacks, using 1 mL of water per vial instead of 2 mL halves the injection volume per peptide. If three peptides each require 0.1 mL per dose, that is 0.3 mL total, which can sometimes be combined into a single syringe draw (from separate vials into one syringe) for a single injection.

The tradeoff is tighter dosing precision. Make sure your doses still fall above 5 units on the syringe for acceptable accuracy.

Strategy 2: Draw multiple peptides into one syringe

Many compatible peptides can be combined in the same syringe for injection. Draw the first peptide, then insert the same needle into the second vial and draw that peptide on top. The total volume is additive.

This only works when the peptides are known to be chemically compatible in solution. BPC-157 and TB-500, for example, are commonly combined this way. Growth hormone secretagogues like ipamorelin and CJC-1295 are also frequently drawn together.

The peptide stack calculator helps plan multi-peptide protocols including reconstitution volumes for each component.

Strategy 3: Reconstitute different vials at different concentrations

If one peptide in your stack requires 500 mcg doses and another requires 100 mcg, using the same water volume for both creates mismatched syringe readings. Instead, adjust water volumes so each peptide dose falls on convenient syringe markings.

For the 500 mcg peptide (5 mg vial): use 2 mL for 2.5 mg/mL, making 500 mcg equal to 20 units.

For the 100 mcg peptide (5 mg vial): use 2.5 mL for 2 mg/mL, making 100 mcg equal to 5 units.

Both doses land on clean syringe markings despite being very different amounts.

Temperature and handling considerations that affect your water calculation

Environmental factors influence reconstitution in ways that affect your effective water volume and peptide concentration.

Altitude and air pressure

At higher altitudes, lower air pressure can cause the rubber stopper to resist needle insertion differently, and drawing water into the syringe may feel slightly different. These are minor effects but worth noting. The actual chemistry of reconstitution is not affected by altitude.

Humidity and storage

Lyophilized peptides are extremely hygroscopic, meaning they absorb moisture from the air. If a vial has been opened or the seal is compromised, the powder may absorb ambient moisture, effectively changing the amount of "dry" peptide before you even add water. Always keep unreconstituted vials sealed and stored according to manufacturer recommendations, typically at -20 degrees Celsius for long-term or 2-8 degrees Celsius for short-term storage.

Post-reconstitution handling

Every time you withdraw a dose, you remove liquid and introduce a tiny amount of air into the vial. Over many draws, the remaining solution becomes slightly more concentrated as proportionally more water evaporates through the tiny stopper channels. This effect is minimal over 2-3 weeks but can become relevant for vials kept for longer periods.

This is another reason to use reconstituted peptides within the 28-day window, not just for sterility but for dosing consistency.

Frequently asked questions

Can I add more water to a peptide vial after initial reconstitution?

Yes, you can add additional bacteriostatic water to an already reconstituted vial to reduce the concentration. This is sometimes done when the initial solution is too concentrated for accurate dosing. Simply calculate the new total water volume (original + added) and recalculate the concentration. The peptide amount stays the same. Just remember that each additional needle puncture increases contamination risk.

What happens if I accidentally add too much water?

The peptide is not damaged. Your solution is simply more dilute than intended. Recalculate the concentration using the actual water volume you added and adjust your dose volume accordingly. You will need to draw more liquid per dose, but the peptide itself is fine. If the resulting injection volume is too large, you may want to start with a fresh vial and use less water.

Do different peptides dissolve at different rates?

Yes. Some peptides dissolve within seconds of water contact. Others can take 5-30 minutes. Factors include the peptide sequence, molecular weight, lyophilization conditions, and the concentration of the resulting solution. Higher concentrations generally take longer to dissolve. Never force dissolution by shaking. If a peptide has not dissolved after 30 minutes of gentle periodic swirling, there may be a solubility issue, and you should consider using a different solvent or adding more water.

Can I use the same syringe to add water and then draw my dose?

Technically possible but not recommended. The syringe that added water has been in contact with the bacteriostatic water vial stopper and potentially your fingers during the process. Using a fresh, sealed syringe for each dose draw maintains the sterile chain and prevents cross-contamination. Syringes are inexpensive compared to the peptide. Always use fresh ones.

How do I know if my bacteriostatic water has gone bad?

Bacteriostatic water has a 28-day use window after first puncture. Signs of compromised water include cloudiness, visible particles, unusual odor, or discoloration. Unopened vials stored at room temperature are typically stable for 2-3 years (check the expiration date). Once opened, mark the date on the vial and discard after 28 days regardless of appearance.

Is there a minimum amount of water I should add?

There is no hard minimum, but practical considerations set a floor. Adding less than 0.5 mL to any vial makes accurate dosing extremely difficult with standard syringes. The exception is highly potent peptides (like semaglutide) where tiny doses of concentrated solution are intentional and where specialized fine-gauge syringes may be used. For most peptides, 0.5 mL is the practical minimum.

Does the water volume affect how fast the peptide works?

No. The water volume affects concentration and injection volume, not pharmacokinetics. Once injected, the peptide enters your body regardless of how concentrated or dilute the solution was. A 250 mcg dose works the same whether it came from 5 units of concentrated solution or 25 units of dilute solution. The timeline for peptide results depends on the compound, dose, and protocol, not the reconstitution volume.

What syringe size is best for peptide dosing?

For most peptide protocols, a 1 mL (100 unit) U-100 insulin syringe works well. If your calculated doses consistently fall below 10 units, a 0.3 mL (30 unit) syringe offers finer graduation marks and better precision. For larger doses above 50 units, you might prefer the 1 mL syringe for its full scale. Learn more in our injection pen guide for alternative delivery methods.

External resources

United States Pharmacopeia (USP) for pharmaceutical water standards

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for injectable preparation guidelines

PubMed for peptide stability and reconstitution research

World Health Organization (WHO) for safe injection practices

CDC Injection Safety for contamination prevention protocols

For researchers committed to getting peptide reconstitution right every time, SeekPeptides provides the most comprehensive tools available. Members access detailed protocols, reconstitution calculators, expert-reviewed dosing guides, and a community of experienced researchers who have navigated these exact questions thousands of times.

In case I do not see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night. Join us here.