Jan 23, 2026

The peptide formula sitting on that vial label holds more information than most people realize, and understanding how to decode it separates casual observers from serious researchers who actually know what they are working with.

Here is the problem most people face. They purchase a peptide, see a string of amino acid codes or a molecular weight listed somewhere, and have no idea what any of it means. Is a 15-amino-acid peptide better than a 43-amino-acid one? What does the molecular formula tell you about stability? How do you even read the shorthand scientists use to describe these sequences?

These questions matter more than most people think. Understanding peptide formulas affects everything from dosage calculations to reconstitution accuracy to recognizing whether that certificate of analysis actually matches what it claims. The difference between getting results and wasting money often comes down to fundamental knowledge that takes maybe thirty minutes to learn properly.

This guide breaks down peptide formulas from basic chemistry to practical application. You will learn how amino acids combine to form peptides, how to read both one-letter and three-letter notation systems, how molecular weight calculations work, and how this knowledge applies to the peptides researchers actually use. SeekPeptides provides resources for researchers who want to move beyond surface-level understanding, and this guide represents the foundation that makes everything else possible.

The building blocks of every peptide formula

Every peptide formula begins with amino acids. These molecules contain both an amino group and a carboxyl group attached to a central carbon atom, along with a unique side chain that gives each amino acid its specific properties. Twenty standard amino acids appear in virtually all biological peptides, though researchers also work with modified and synthetic variants that expand the possibilities considerably.

The general molecular formula for any amino acid follows a consistent pattern. NH2-CHR-COOH represents the basic structure, where R indicates the variable side chain that distinguishes one amino acid from another. Glycine carries the simplest side chain, just a hydrogen atom, while tryptophan carries one of the most complex, featuring an indole ring system that contributes substantial molecular weight.

Bioregulator peptides use these same twenty amino acids arranged in specific sequences that determine biological activity. The sequence matters enormously. Changing even a single amino acid can completely alter how a peptide functions, which explains why researchers pay such close attention to accurate identification and verification.

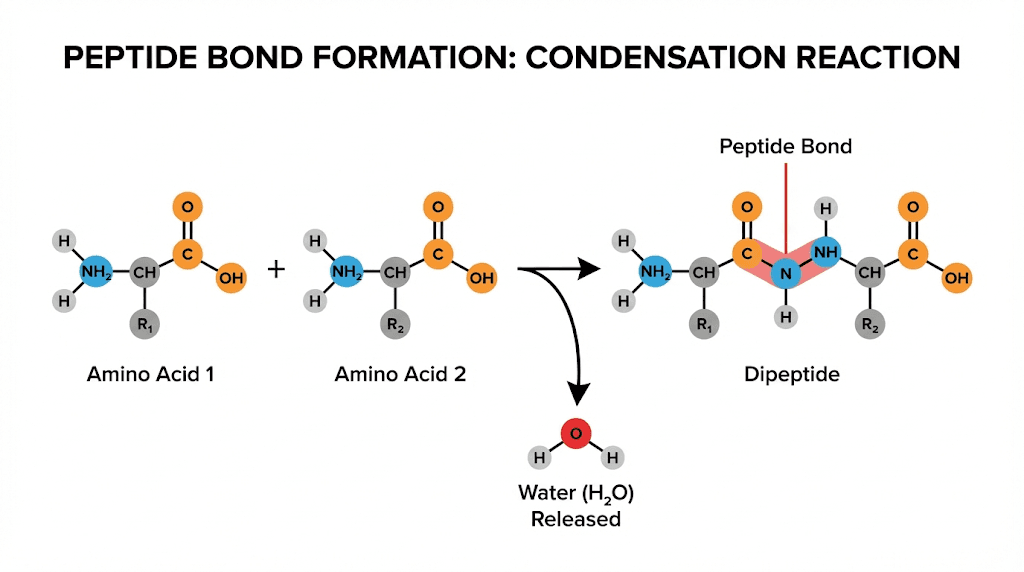

How amino acids connect to form peptides

Peptide bonds form through condensation reactions. When two amino acids join, the carboxyl group of one releases a hydroxyl group while the amino group of the other releases a hydrogen. These combine to form water, and the remaining atoms form a covalent bond between the carbon and nitrogen.

This bond has special properties that affect peptide behavior. It is partially double in character, meaning it does not rotate freely like a typical single bond. The rigidity created by this partial double bond character gives peptides their specific three-dimensional shapes, and those shapes determine biological activity.

Understanding this bond formation matters for peptide reconstitution and storage. The peptide bond is relatively stable under normal conditions but can hydrolyze, meaning it breaks apart by adding water back, under extreme pH conditions or prolonged exposure to heat. This explains why proper storage protects your investment.

Proper peptide storage depends on understanding these chemical realities. Lyophilized peptides remain stable because removing water prevents the reverse reaction that would break those bonds. Once reconstituted, the clock starts ticking because water is now available to potentially disrupt the structure.

Naming peptides by length

Peptide terminology follows consistent rules based on amino acid count. A dipeptide contains two amino acids. A tripeptide contains three. These small molecules represent the simplest peptides and often serve as carrier molecules or signaling compounds in biological systems.

Oligopeptides span the range from roughly two to twenty amino acids. Most research peptides fall into this category. BPC-157, for example, is a pentadecapeptide, meaning it contains fifteen amino acids. GHK-Cu is a tripeptide, containing just three amino acids plus a copper ion that forms part of its functional structure.

Polypeptides contain more than twenty amino acids but have not yet reached protein territory. TB-500, the synthetic fragment of thymosin beta-4, contains 43 amino acids and sits at the upper end of what most researchers consider a peptide rather than a small protein. The distinction matters for regulatory purposes and for understanding how these molecules behave in biological systems.

Reading peptide notation systems

Two standard systems exist for writing peptide sequences. Both serve specific purposes, and researchers encounter both regularly. Learning to read both systems fluently saves time and prevents confusion when examining certificates of analysis or comparing peptide sources.

The three-letter code came first historically. Each amino acid receives an abbreviation typically derived from its name. Alanine becomes Ala. Glycine becomes Gly. Histidine becomes His. When writing a peptide sequence, these codes connect with hyphens to show the order of amino acids from one end to the other.

The one-letter code developed for computational purposes and for describing longer sequences efficiently. Each amino acid receives a single capital letter. Alanine is A. Glycine is G. Histidine is H. No hyphens or separators appear between letters, making sequences compact but requiring memorization of the code to read fluently.

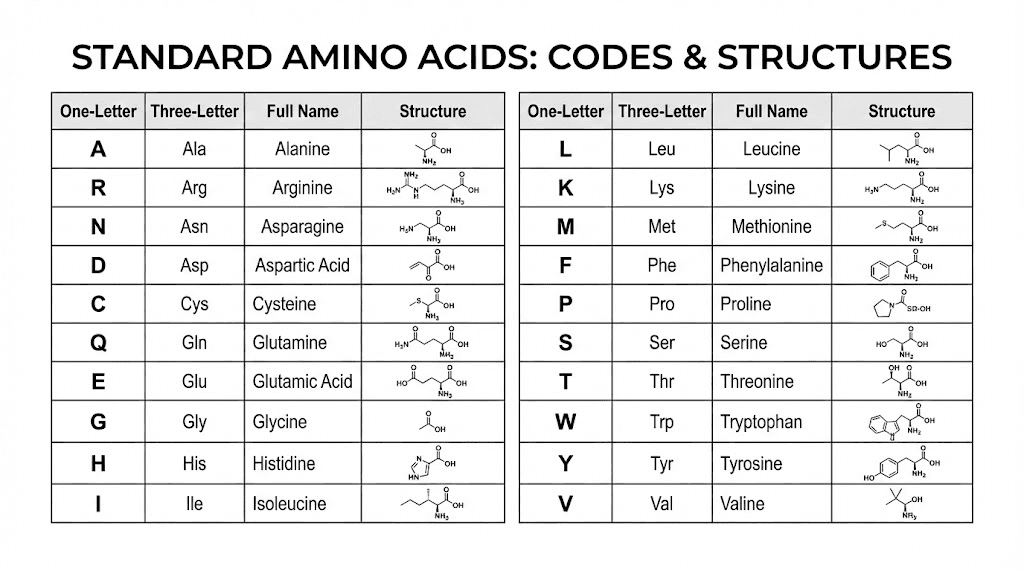

The complete amino acid code reference

The twenty standard amino acids and their codes form the foundation of peptide notation. Understanding these allows you to read any peptide sequence and recognize what amino acids are present.

Glycine carries the codes Gly and G. It is the smallest amino acid with no chiral center. GHK-Cu dosing protocols begin with this amino acid, as the tripeptide sequence starts Gly-His-Lys.

Alanine uses Ala and A. Cysteine uses Cys and C. Aspartic acid uses Asp and D. Glutamic acid uses Glu and E. Phenylalanine uses Phe and F.

Histidine carries His and H. This amino acid appears in many longevity-focused peptides due to its role in metal binding and its presence in important signaling molecules.

Isoleucine uses Ile and I. Lysine uses Lys and K. Leucine uses Leu and L. These branched-chain and basic amino acids appear frequently in muscle-supporting peptides.

Methionine uses Met and M. Asparagine uses Asn and N. Proline uses Pro and P. Glutamine uses Gln and Q.

Arginine uses Arg and R. Serine uses Ser and S. Threonine uses Thr and T. Valine uses Val and V. Tryptophan uses Trp and W. Tyrosine uses Tyr and Y.

Two additional codes handle situations where exact identification is uncertain. B indicates either aspartic acid or asparagine when these have not been distinguished. Z indicates either glutamic acid or glutamine. X represents any amino acid or an unknown residue.

Reading sequences from N-terminus to C-terminus

All peptide sequences follow a standard orientation. The N-terminus, which carries a free amino group, appears on the left. The C-terminus, which carries a free carboxyl group, appears on the right. This convention is universal and never varies.

When you see Gly-His-Lys written for GHK-Cu, glycine sits at the N-terminal position and lysine sits at the C-terminal position. The copper ion coordinates primarily with the histidine residue in the middle of the sequence, which explains why the full name includes Cu at the end.

This directionality matters for oral peptide delivery and for understanding how peptides interact with biological targets. Enzymes that break down peptides often work from one terminus or the other, so knowing which end is which helps predict stability.

Nasal spray peptide formulations often include modifications at one terminus or the other to improve stability. Acetylation at the N-terminus or amidation at the C-terminus can protect peptides from enzymatic degradation while maintaining biological activity.

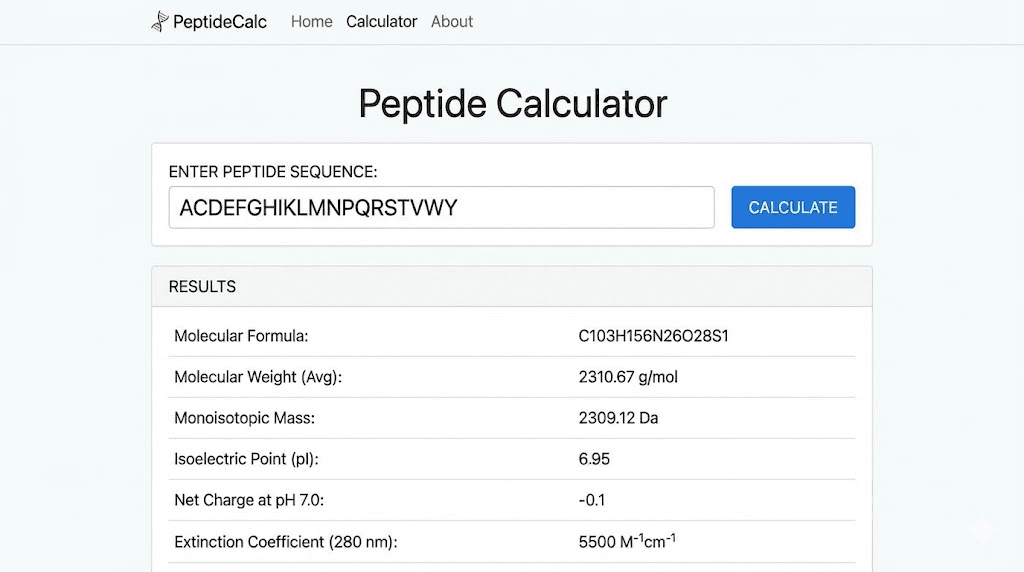

Calculating peptide molecular weight

Molecular weight determines everything from dosing accuracy to reconstitution calculations.

Every peptide has a specific molecular weight expressed in Daltons or grams per mole. These units are functionally equivalent for practical purposes, though Daltons appear more commonly in peptide contexts.

The calculation itself is straightforward in concept. Add up the molecular weights of all amino acid residues in the sequence, then account for the water molecules lost during peptide bond formation. Each peptide bond represents one water molecule removed, so a peptide with n amino acids will have lost n-1 water molecules during synthesis.

For practical purposes, the peptide calculator handles these calculations automatically. Enter your sequence in either notation system, and the calculator returns molecular weight along with other useful parameters.

Why molecular weight matters for dosing

Peptide doses are typically expressed in micrograms or milligrams of the actual peptide. When you see a recommendation for 250mcg of BPC-157, that refers to the mass of the peptide itself, not the total contents of the vial which may include carriers or salts.

Different peptides with different molecular weights will have different numbers of molecules in the same mass. A 100mcg dose of a small tripeptide like GHK-Cu contains far more individual molecules than a 100mcg dose of a larger peptide like TB-500. This matters for understanding potency and for comparing peptides to each other.

Dosing guides account for these differences when providing recommendations. A peptide with a lower molecular weight might require a higher mass dose to achieve similar receptor occupancy as a peptide with a higher molecular weight, though the relationship is not always linear due to differences in binding affinity and biological activity.

The BPC-157 dosage calculator uses molecular weight as part of its calculations, converting between different units and accounting for body weight when appropriate.

Molecular formula versus molecular weight

These two terms are related but distinct. The molecular formula tells you exactly how many atoms of each element are present in one molecule. The molecular weight is the sum of the atomic masses of all those atoms.

For BPC-157, the molecular formula is C62H98N16O22. This tells you the peptide contains 62 carbon atoms, 98 hydrogen atoms, 16 nitrogen atoms, and 22 oxygen atoms. The molecular weight calculates to approximately 1419 Daltons, though exact values depend on which isotopes you use in the calculation.

Knowing the molecular formula helps verify peptide identity. Third-party testing labs use mass spectrometry to confirm that the measured molecular weight matches the expected value for a given peptide. Significant deviations suggest the peptide is not what it claims to be or has undergone degradation.

Quality peptide sources provide certificates of analysis that include mass spectrometry data. Learning to read these certificates requires understanding what the molecular weight should be for your specific peptide.

Common research peptide formulas

Different peptides have vastly different formulas, and understanding these differences helps researchers appreciate what they are working with. Here are the formulas for some of the most commonly researched peptides, along with what those formulas tell us about their properties.

BPC-157 formula and structure

BPC-157 stands for Body Protection Compound-157, and its formula reflects its complexity. The molecular formula C62H98N16O22 corresponds to a 15-amino-acid sequence derived from a protein found in human gastric juice.

The amino acid sequence reads: Gly-Glu-Pro-Pro-Pro-Gly-Lys-Pro-Ala-Asp-Asp-Ala-Gly-Leu-Val. In one-letter code, that becomes GEPPPGKPADDAGLV. Each position contributes specific properties to the overall peptide function.

Notice the three consecutive proline residues near the N-terminus. Proline creates kinks in peptide chains because its side chain bonds back to the backbone nitrogen. This gives BPC-157 a specific three-dimensional structure that likely contributes to its biological activity. BPC-157 administration methods need to preserve this structure to maintain effectiveness.

The molecular weight of approximately 1419 Da places BPC-157 in the middle range for research peptides. It is large enough to have significant biological activity but small enough to potentially cross membranes and reach target tissues. Comparing oral versus injectable BPC-157 involves understanding how this molecular weight affects absorption through different routes.

GHK-Cu formula and copper coordination

GHK-Cu has one of the simplest formulas among research peptides. The tripeptide portion is just Gly-His-Lys, which gives a formula of C14H24N6O4 for the peptide alone. But the copper ion is essential, bringing the complete formula to C14H23CuN6O4 with a molecular weight of approximately 403 Da.

The copper does not just tag along passively. It coordinates with the peptide through specific interactions with the histidine and lysine residues, creating a stable complex that maintains its structure in solution. This complex delivers copper to tissues in a bioavailable form that can serve as a cofactor for various enzymes.

GHK-Cu for hair research depends on this copper delivery mechanism. The copper serves as an essential cofactor for enzymes involved in tissue maintenance and regeneration, which explains why the peptide has effects beyond what the amino acid sequence alone would predict.

The low molecular weight of GHK-Cu makes it one of the most accessible peptides for topical research applications. Topical copper peptide formulations can achieve meaningful tissue concentrations because the small size allows penetration through barriers that would stop larger peptides.

TB-500 formula and the thymosin connection

TB-500 represents a larger and more complex formula. As a 43-amino-acid synthetic analog of thymosin beta-4, its molecular formula runs considerably longer. The exact sequence contains multiple charged residues that affect solubility and stability in ways that differ significantly from smaller peptides.

The key functional domain within TB-500 includes the sequence LKKTET, which appears to mediate many of the peptide's biological effects related to actin binding and cell migration. Understanding where this sequence sits within the larger formula helps researchers appreciate what portions of the molecule are most important for activity.

TB-500 research applications often involve combining it with other peptides like BPC-157. The different formulas and mechanisms of these peptides may produce complementary effects, which explains the popularity of various peptide stacking protocols.

The higher molecular weight of TB-500 affects handling requirements. Larger peptides are generally more susceptible to denaturation during handling, which makes proper temperature management more critical.

How to verify peptide formulas

Knowing the expected formula for your peptide allows you to verify what you actually receive. This skill separates researchers who trust blindly from those who verify systematically. The peptide market includes products of varying quality, and verification protects both your results and your investment.

Reading certificates of analysis

Any reputable peptide source provides a certificate of analysis with each batch. These documents contain analytical data confirming the identity and purity of the product. Learning to read these certificates requires understanding what the numbers mean.

Mass spectrometry results should show a primary peak at the expected molecular weight for your peptide. For BPC-157, that peak should appear around 1419 Da. Some variation exists due to instrumentation differences and ionization patterns, but the measured value should be within a few Daltons of the expected value.

Peptide vial contents should match what the certificate claims. If the certificate shows a molecular weight significantly different from the expected formula, something is wrong. Either the peptide is not what it claims to be, or it has degraded or been contaminated.

HPLC purity data tells you what percentage of the sample is the intended peptide versus impurities or degradation products. Research-grade peptides typically specify 98% or higher purity. Lower purity means more of your vial contains something other than the peptide you are trying to research.

Third-party testing options

Independent testing provides the highest confidence in peptide identity. Several laboratories accept peptide samples for mass spectrometry confirmation, allowing researchers to verify that what they received matches what they ordered.

The cost of testing varies but typically runs less than the cost of the peptide itself for premium products. Consider testing a valuable investment rather than an unnecessary expense. The information gained can prevent wasted time researching with the wrong compound.

Pharmaceutical-grade versus research-grade peptides differ substantially in testing requirements. Pharmaceutical production requires extensive testing at multiple stages, while research-grade products may only receive final product testing if that.

When evaluating different peptide sources, the availability and quality of analytical data should factor into your decision. Sources that provide detailed certificates of analysis with batch-specific data demonstrate more commitment to quality than those providing generic or outdated documentation.

Understanding purity specifications

Purity percentage tells you how much of the sample is the desired peptide. A 99% pure sample means roughly 1% of the contents are something else. That something else might be synthesis byproducts, truncated sequences, deletion products, or degradation compounds.

For most research applications, 98% or higher purity is adequate. Some particularly sensitive applications might require 99% or higher. Going below 95% introduces enough impurity that results become harder to interpret.

The grey market peptide landscape includes products of widely varying purity. Prices that seem too good often correspond to lower purity or inadequate testing. Understanding what purity level you need helps you evaluate whether a bargain is actually a bargain.

Salt forms affect reported purity in ways that confuse some researchers. Many peptides are supplied as acetate or trifluoroacetate salts, which add to the total mass but are not part of the active peptide. A certificate might list peptide content separately from total material to account for this.

Peptide formulas in skincare and cosmetics

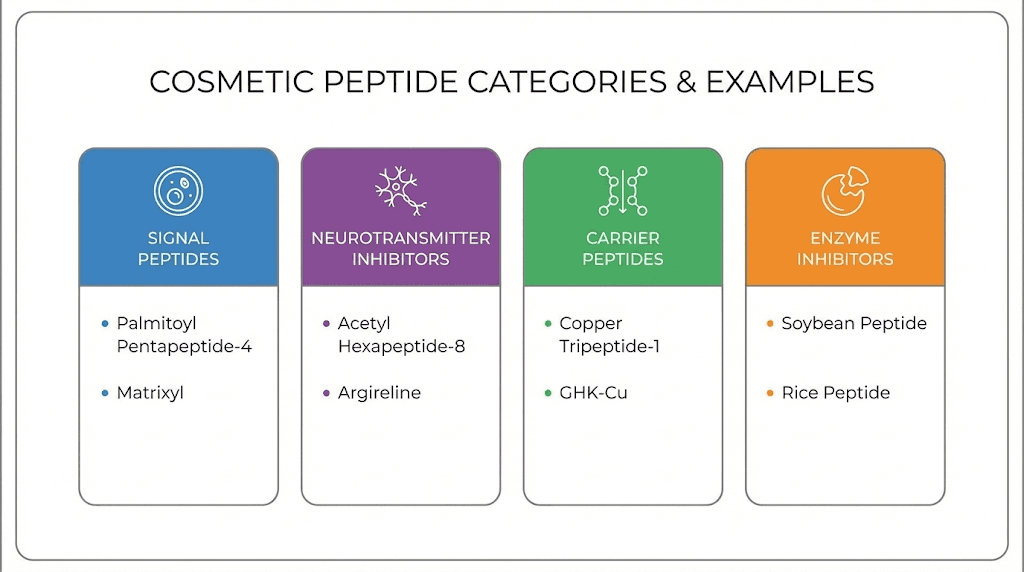

The same peptide chemistry that applies to research peptides appears in skincare products, though the applications and regulatory frameworks differ substantially. Understanding how peptide formulas translate to cosmetic applications helps researchers appreciate the broader context of peptide science.

Signal peptides and collagen production

Signal peptides work by mimicking the fragments that result when collagen breaks down. The body interprets these signals as evidence of damage and responds by increasing collagen production. This mechanism forms the basis for many anti-aging claims in peptide skincare.

Palmitoyl tripeptide-1, often appearing as Matrixyl or similar trade names, is a three-amino-acid sequence with a palmitic acid modification that improves skin penetration. The core tripeptide mimics a collagen fragment, signaling fibroblasts to increase collagen synthesis.

Skin tightening peptides use variations on this theme. Different sequences signal different responses, and combining multiple signal peptides can theoretically amplify effects by engaging multiple signaling pathways simultaneously.

Matrixyl 3000 combines two peptides, palmitoyl tripeptide-1 and palmitoyl tetrapeptide-7, to engage complementary pathways. The formulas differ in their amino acid sequences but share the palmitic acid modification that helps them penetrate skin.

Neurotransmitter-inhibiting peptides

Some cosmetic peptides work by reducing muscle contraction rather than stimulating collagen production. These neurotransmitter inhibitors take a completely different approach to addressing wrinkles, targeting the muscle movements that create expression lines.

Argireline, or acetyl hexapeptide-3, is a six-amino-acid sequence that interferes with the release of neurotransmitters at the neuromuscular junction. The formula mimics a portion of the SNARE complex involved in neurotransmitter release, theoretically reducing muscle contraction without complete paralysis.

Syn-Ake, or dipeptide diaminobutyroyl benzylamide diacetate, is a tripeptide derivative designed to mimic waglerin-1, a component of temple viper venom. The formula does not actually contain venom but uses a synthetic sequence with similar activity at acetylcholine receptors.

Commercial peptide serums often combine multiple peptide types to address wrinkles through multiple mechanisms. A single product might include signal peptides for collagen, neurotransmitter inhibitors for expression lines, and carrier peptides for delivery of other active ingredients.

Carrier peptides and copper delivery

Carrier peptides serve a different function altogether. Rather than signaling biological responses directly, they transport other molecules to where they are needed. GHK-Cu is the most famous example, carrying copper ions that serve as essential cofactors for numerous enzymes.

The tripeptide formula of GHK-Cu makes it small enough to penetrate skin effectively while still binding copper tightly enough to transport it successfully. This balance explains why GHK-Cu appears so frequently in copper peptide serums and why it works better than simply applying copper salts.

Combining copper peptides with other actives requires understanding the chemistry involved. Copper can interact with other ingredients, particularly vitamin C, in ways that reduce effectiveness or cause unwanted reactions. The peptide formula itself is stable, but formulation matters.

Enzyme inhibitor peptides represent yet another category. These peptides work by blocking enzymes that break down collagen or elastin. Rather than stimulating production of new structural proteins, they protect existing proteins from degradation. The formulas target specific enzyme active sites.

Understanding modified peptide formulas

Many peptides used in research are not exact copies of natural sequences. Modifications to the basic amino acid formula can improve stability, increase potency, or alter tissue distribution. Recognizing these modifications helps researchers understand what they are actually working with.

N-terminal and C-terminal modifications

The free amino group at the N-terminus and the free carboxyl group at the C-terminus represent vulnerable points where enzymes can begin degrading a peptide. Modifications at these positions can dramatically extend peptide half-life in biological systems.

Acetylation adds an acetyl group to the N-terminus, removing the free amino group that certain enzymes recognize. This modification appears in numerous research peptides, including various nootropic peptides where extended duration of action is desirable.

Amidation converts the C-terminal carboxyl group to an amide, eliminating another enzyme recognition site. Many naturally occurring peptide hormones are amidated, suggesting evolution has already discovered this stabilization strategy.

When reading peptide formulas, look for notation indicating these modifications. Ac- at the beginning of a sequence indicates acetylation. -NH2 at the end indicates amidation. These modifications add small amounts to the molecular weight that should appear in mass spectrometry data.

Amino acid substitutions and analogs

Some peptides replace natural amino acids with synthetic analogs that resist enzymatic degradation. D-amino acids, which are mirror images of the naturally occurring L-forms, cannot be processed by most enzymes designed to work with L-amino acids.

Substituting D-amino acids at strategic positions can create peptides that maintain biological activity while resisting degradation. The formula technically remains the same, since D and L forms have identical molecular weights, but the behavior differs substantially.

Peptide therapy costs can vary based on how extensively a peptide has been modified. Simple sequences are relatively inexpensive to synthesize. Heavily modified sequences with non-standard amino acids or complex post-translational modifications require specialized synthesis that increases cost.

Cyclization connects the N-terminus to the C-terminus or joins side chains within the sequence, creating a ring structure. Cyclic peptides often have improved stability and can show enhanced binding to targets. The formula includes the same atoms but arranged in a different topology.

Peptide conjugates and complexes

Some peptide formulas include non-peptide components that modify properties.

GHK-Cu is the classic example, where a copper ion is integral to the structure and function. The complete formula must include this metal to accurately represent the molecule.

Fatty acid conjugates attach lipid chains to peptides to improve membrane penetration or alter distribution. The palmitic acid in cosmetic peptides like Matrixyl serves this purpose. The formula grows substantially larger with these modifications.

PEGylation attaches polyethylene glycol chains to peptides, dramatically increasing molecular weight and altering pharmacokinetics. PEGylated peptides circulate longer and may show reduced immunogenicity. The formula becomes much more complex with these modifications.

Oral versus injectable peptide delivery often involves formulation strategies that protect peptides from digestive enzymes without necessarily modifying the peptide formula itself. Nanoparticle encapsulation or enteric coating can achieve similar protective effects through physical rather than chemical means.

Peptide formula databases and resources

Researchers can access extensive databases containing peptide sequence and formula information. These resources help verify expected molecular weights, compare peptide structures, and understand sequence-function relationships.

Online peptide calculators

Multiple free online tools convert peptide sequences to molecular formulas and weights. These calculators accept input in either one-letter or three-letter notation and return molecular formula, molecular weight, isoelectric point, and other useful parameters.

Bachem, Biosynth, and several other peptide manufacturers provide free calculators on their websites. Academic resources like ExPASy ProtParam offer similar functionality with additional analytical options. These tools make formula calculations accessible to anyone with the sequence information.

The peptide stack calculator helps researchers planning combination protocols understand the total peptide load they will be working with. Entering multiple sequences returns combined molecular weight and can help with dose planning.

For unusual or modified sequences, more specialized tools may be necessary. Pep-Calc handles non-standard amino acids and can generate chemical drawings of peptide structures. Some tools can even predict potential synthesis difficulties based on the sequence.

Literature and database resources

Scientific literature contains detailed information about peptide formulas, mechanisms, and research findings. PubMed provides free access to abstracts and many full-text articles covering peptide research across all fields.

The Protein Data Bank contains three-dimensional structures for many peptides, showing how the amino acid sequence folds into functional shapes. Understanding structure-function relationships requires this spatial information that flat sequences cannot convey.

Peptide research forums often discuss specific peptides in detail, including formula verification and comparison between sources. Community knowledge can supplement formal resources, though information quality varies.

Manufacturer literature, including product specifications and certificates of analysis, provides batch-specific formula information. Collecting and comparing these documents across suppliers can reveal consistency or raise concerns about quality control.

Academic and research resources

University libraries provide access to comprehensive databases that may not be freely available. Researchers affiliated with academic institutions can access resources like SciFinder, which searches chemical structures and formulas across millions of compounds.

Review articles summarize current knowledge about specific peptide families, including formula variations and structure-activity relationships. These reviews save time compared to reading primary literature and provide context for individual findings.

Peptide validation tools use computational methods to assess sequence accuracy and predict properties. These resources become more valuable as peptide research grows more sophisticated and as the number of available sequences increases.

Textbooks on peptide chemistry cover fundamental concepts in depth. While not always current on the latest research peptides, they provide the foundational knowledge needed to understand any peptide formula you encounter.

Practical applications of formula knowledge

Understanding peptide formulas is not academic exercise. This knowledge directly affects practical aspects of peptide research from ordering to reconstitution to dosing. Here is how formula knowledge translates to real-world benefits.

Ordering and verifying peptides

When ordering peptides, knowing the expected formula allows you to verify that product descriptions are accurate. Some vendors provide detailed formula information while others provide only names. Vendors that include molecular formula and weight demonstrate higher transparency.

Comparing products between vendors becomes easier with formula knowledge. If two vendors claim to sell the same peptide but list different molecular weights, something is wrong somewhere. Either one vendor is incorrect, or they are selling different products under the same name.

Vendor evaluations should include assessment of technical accuracy in product listings. Errors in molecular weight or formula suggest either carelessness or lack of expertise, neither of which inspires confidence in product quality.

Understanding that peptides often come as salts affects how you interpret stated quantities. If a vial contains 5mg of BPC-157 acetate, the actual peptide content is slightly less because some of that mass is acetate. Formula knowledge helps you understand these distinctions.

Reconstitution calculations

Accurate reconstitution requires knowing how much peptide is in your vial and how much solvent you will add. The resulting concentration determines dosing accuracy for all subsequent research. Getting this calculation wrong undermines everything that follows.

Molecular weight plays into concentration calculations when working with molar concentrations. Most researchers work in mass concentrations like mcg/mL, which simplifies calculations, but some protocols specify molar concentrations that require molecular weight for conversion.

The reconstitution guide walks through these calculations step by step. Understanding the formula helps you catch errors and verify that your calculations make sense.

Choosing the right solvent depends partly on peptide properties that relate to the formula. Highly charged peptides may require different conditions than neutral peptides. Hydrophobic sequences may need surfactants or organic cosolvents.

Stability considerations

Different amino acids contribute different stability profiles. Sequences containing methionine can oxidize. Sequences containing asparagine can deamidate. Sequences containing multiple acidic residues may be sensitive to pH changes. Knowing the formula helps predict potential stability issues.

Reconstituted peptide shelf life varies based on sequence characteristics. Some peptides remain stable for weeks under proper refrigeration. Others degrade within days. The amino acid composition provides clues about expected stability.

Protecting peptides during handling and storage becomes easier when you understand what can go wrong. Avoiding conditions that promote oxidation matters most for methionine-containing peptides. Maintaining appropriate pH matters most for sequences with multiple ionizable residues.

Long-term storage strategies should account for specific peptide vulnerabilities. Aliquoting into single-use portions prevents repeated freeze-thaw cycles that can damage some peptides. Storing with desiccant prevents moisture damage to lyophilized material.

Advanced formula concepts

Beyond basic sequence notation, advanced concepts help researchers understand the full complexity of peptide chemistry. These topics become relevant as researchers move beyond simple applications to more sophisticated work.

Isomers and stereochemistry

Amino acids except glycine have at least one chiral center, meaning they can exist in mirror-image forms. Natural proteins use almost exclusively L-amino acids. D-amino acids occur rarely in nature but appear in some bacterial peptides and synthetic analogs.

The molecular formula does not distinguish between L and D forms since they contain the same atoms. Specific notation like (D) or small caps indicates stereochemistry when relevant. For most research peptides, L-configuration is assumed unless specified otherwise.

Isomerization can occur during synthesis or storage, converting some L-amino acids to D-forms. This changes peptide properties even though the formula appears unchanged. Quality control should include tests for isomeric purity.

Lyophilized versus liquid storage affects isomerization rates. Liquid solutions generally show more degradation over time, including potential isomerization.

Lyophilized material is more stable but requires proper handling during reconstitution.

Post-translational modifications

Natural peptides often carry modifications beyond the basic amino acid sequence. Phosphorylation adds phosphate groups to serine, threonine, or tyrosine. Glycosylation adds sugar chains. These modifications change both the formula and the biological activity.

Synthetic peptides can include these modifications but at increased cost and complexity. Modified peptides may better replicate natural signaling but require specialized synthesis and characterization. Understanding what modifications are present affects interpretation of research results.

The formula notation for modified peptides uses specific conventions. pS indicates phosphoserine. Glycosylation sites may be indicated with the attached sugar structure. These notations add complexity to formulas but provide important information.

Some bioregulator peptides contain natural post-translational modifications that contribute to their activity. Synthetic versions may or may not include these modifications depending on the synthesis approach.

Peptide aggregation and higher-order structure

Some peptides spontaneously form dimers, trimers, or larger aggregates under certain conditions. The formula for an individual peptide does not change, but the functional form may be multiple peptides associated together.

Aggregation can be beneficial or harmful depending on the peptide and application. Some peptides require dimerization for activity. Others lose activity when they aggregate. Understanding aggregation behavior helps optimize handling and storage.

Disulfide bonds between cysteine residues can link peptide chains together, either within a single peptide or between multiple peptides. These bonds add additional stability but can also scramble during improper handling, creating incorrect linkages.

Combining multiple peptides raises questions about potential interactions. Some peptides might aggregate with each other when mixed. Understanding the formulas and properties of each component helps predict compatibility.

Frequently asked questions

What is the general formula for a peptide?

The general formula depends on which amino acids are present and how many. Each amino acid contributes its specific atoms, minus one water molecule lost for each peptide bond formed. A dipeptide with two amino acids loses one water. A tripeptide with three amino acids loses two waters. The peptide calculator handles these calculations automatically when you enter a sequence.

How do I calculate the molecular weight of a peptide?

Add the molecular weights of all amino acid residues, then subtract 18 Daltons for each peptide bond to account for water loss during condensation. For a 10-amino-acid peptide, subtract 9 times 18, which equals 162 Daltons, from the sum of amino acid molecular weights. Online calculators make this process simple for any sequence you need to analyze.

What is the difference between one-letter and three-letter amino acid codes?

Three-letter codes like Gly, Ala, Leu are more readable and used for shorter sequences. One-letter codes like G, A, L are more compact and used for longer sequences or computational applications. Both systems represent the same amino acids and can be converted between formats. The alpha peptides guide uses standard notation throughout.

Why does GHK-Cu include copper in its formula?

GHK-Cu is a tripeptide that forms a stable complex with copper ions through coordination bonds with the histidine and lysine residues. The copper is essential for biological activity, not just an additive or salt form. The complete functional molecule includes both the peptide and the metal, which is why both appear in the name and should appear in proper formulas.

How can I verify that a peptide matches its expected formula?

Request a certificate of analysis that includes mass spectrometry data. The measured molecular weight should match the expected value for the stated sequence within a few Daltons. Significant deviations suggest either incorrect identity or degradation. Third-party testing provides independent verification when vendor certificates are insufficient.

Do modified peptides have different formulas than unmodified versions?

Yes. N-terminal acetylation adds 42 Daltons. C-terminal amidation adds approximately 1 Dalton while removing about 17, for a net change of roughly negative 16 Daltons. Other modifications add their respective molecular weights. Always verify which form you are working with since modifications affect calculated concentrations and expected mass spectrometry results.

What formula information should a certificate of analysis include?

A complete certificate should include the amino acid sequence, molecular formula, expected molecular weight, measured molecular weight from mass spectrometry, and purity data from HPLC or similar methods. Additional information like counterion identity, peptide content as percentage of total mass, and appearance are also valuable. The peptide vial research guide covers certificate interpretation in detail.

For researchers ready to move beyond understanding formulas to applying that knowledge in practical protocols, SeekPeptides provides comprehensive guidance. Members access detailed protocol information, dosing resources, and community support from experienced researchers who have navigated these exact questions. The formula knowledge you have gained here serves as the foundation for everything that follows.