Jan 27, 2026

You have probably encountered this question on an exam or in a biochemistry textbook. The peptide alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine appears frequently in academic settings because it perfectly illustrates the fundamental principles of peptide chemistry. Five amino acids. Four peptide bonds. Two carboxyl groups. One free amino group. These numbers matter because they reveal how peptides are constructed at the molecular level, and understanding this construction is essential for anyone working with peptides in any capacity.

But here is where it gets interesting. This seemingly simple sequence contains everything you need to understand about peptide nomenclature, bond counting, and structural analysis. Once you master how to dissect alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine, you can analyze any peptide thrown your way. The principles scale. From dipeptides to massive polypeptides with hundreds of residues, the same rules apply. The same logic holds. And the same counting methods work every single time.

This guide breaks down alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine completely. We will examine each amino acid in the sequence, trace the peptide bonds connecting them, identify the functional groups, and understand why this particular combination has the properties it does. We will also explore how this knowledge applies to peptide formulas you might encounter in research, supplementation, or therapeutic applications. By the end, you will have the tools to analyze any peptide sequence with confidence.

SeekPeptides members often ask about peptide chemistry fundamentals because understanding structure helps them grasp how different peptides work in the body. This foundational knowledge makes everything else click into place.

Breaking down the name: what alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine actually means

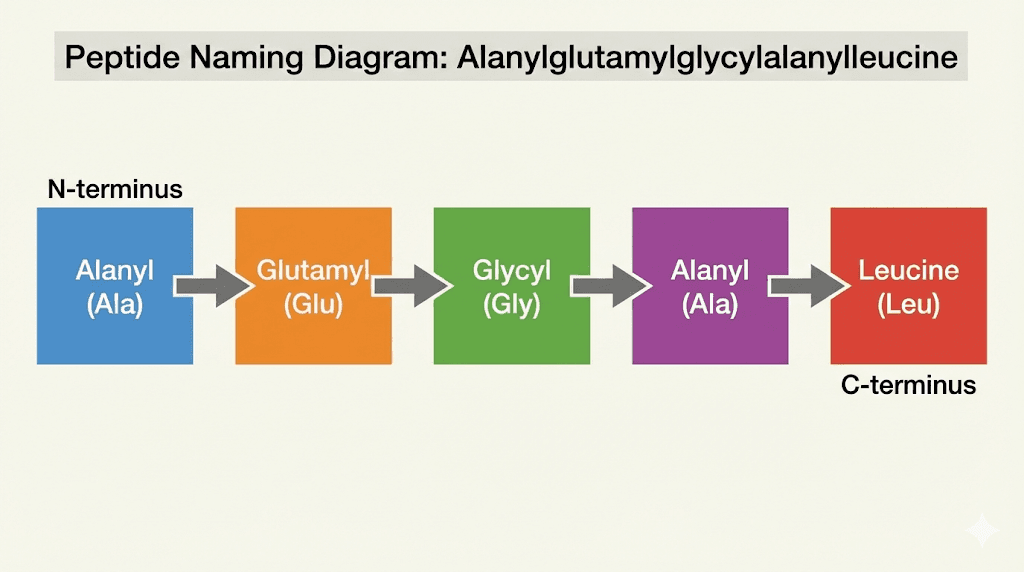

The name looks intimidating. Alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine. But peptide nomenclature follows strict rules that make decoding any peptide name straightforward once you learn the system. Each part of this name corresponds to a specific amino acid, listed in order from the N-terminus to the C-terminus.

Let us break it down piece by piece.

Alanyl comes from alanine. Glutamyl comes from glutamic acid. Glycyl comes from glycine. The second alanyl is another alanine. And leucine stands on its own at the end because it occupies the C-terminal position. When you see the suffix "yl" attached to an amino acid name, it indicates that amino acid has formed a peptide bond with the next residue in the chain. The final amino acid keeps its original name because it has not bonded to anything on its carboxyl side.

So the sequence reads: Ala-Glu-Gly-Ala-Leu. Using single letter codes, this becomes AEGSL. Five amino acids in a specific order, creating what biochemists call a pentapeptide.

The international naming conventions

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB) established these naming conventions to ensure universal consistency. When researchers in Tokyo discuss a peptide with colleagues in London or New York, everyone uses the same language. The rules are precise. You always write sequences from N-terminus to C-terminus, reading left to right. This mirrors the direction of protein synthesis in living cells.

The naming system serves a practical purpose beyond standardization. It tells you exactly what you are dealing with. When you see alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine written out, you know immediately that alanine starts the chain and leucine ends it. You know the sequence has five residues. You can visualize the structure before ever looking at a molecular diagram.

Three letter codes versus single letter codes

Biochemists use two abbreviation systems. The three letter codes, like Ala for alanine, Glu for glutamic acid, Gly for glycine, and Leu for leucine, appear in most educational materials and research papers. They are more intuitive for beginners because the abbreviation often matches the amino acid name.

Single letter codes save space when dealing with long sequences. A becomes alanine, E becomes glutamic acid, G becomes glycine, L becomes leucine. Our pentapeptide becomes simply AEGSL. When you are analyzing bioregulator peptides with dozens of residues, single letter notation keeps things manageable.

The five amino acids in detail

Each amino acid in alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine brings unique properties to the chain. Understanding what makes each one special helps you predict how the complete peptide will behave.

Alanine: the simple starter and internal builder

Alanine appears twice in our sequence. Once at the N-terminus, once in the fourth position. It is among the simplest amino acids, with a methyl group (CH3) as its side chain. This small, nonpolar side chain makes alanine incredibly versatile. It fits almost anywhere in a peptide structure without causing steric clashes.

The nonpolar nature of alanine means it tends to avoid water. In larger proteins, alanine residues often end up buried in the hydrophobic core. In our pentapeptide, the two alanines contribute to overall hydrophobicity without dominating the molecule's character.

Alanine has a strong tendency to form alpha helices in proteins. This structural preference matters when peptides adopt specific three dimensional shapes. The helix-forming propensity of alanine is one reason it appears so frequently in biological peptides and proteins across all domains of life.

Glutamic acid: the acidic contributor

Glutamic acid sits in the second position. Its side chain contains an additional carboxyl group, making it one of the acidic amino acids. This extra carboxyl group is why alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine has two carboxyl groups total rather than just one at the C-terminus.

At physiological pH, the side chain carboxyl group of glutamic acid carries a negative charge. This charge influences how the peptide interacts with water, other molecules, and biological membranes. Charged residues like glutamic acid often appear on the surface of proteins where they can interact with the aqueous environment.

The presence of glutamic acid also affects the peptide's isoelectric point, the pH at which the molecule carries no net charge. Understanding these properties matters when you are working with peptide solutions and need to predict solubility or stability.

Glycine: the flexible middle

Glycine occupies the third position. It is the simplest of all amino acids, with just a hydrogen atom as its side chain. This minimal structure gives glycine unique properties. Without a bulky side chain, glycine can adopt conformations that would be impossible for other amino acids.

This flexibility comes with a trade off. Glycine has a low tendency to form regular secondary structures like alpha helices or beta sheets. It often appears in loops and turns where flexibility is needed. In tissue repair peptides and collagen peptides, glycine plays essential structural roles precisely because of this flexibility.

The small size of glycine also means it can fit in tight spaces. Where other amino acids would clash, glycine slips through. This property makes glycine invaluable in the tightly wound triple helix of collagen, where every third residue must be glycine.

Leucine: the hydrophobic terminator

Leucine ends the sequence. Its side chain is an isobutyl group, making leucine one of the larger nonpolar amino acids. This hydrophobic character means leucine strongly avoids water.

In larger proteins, leucine residues typically cluster in the hydrophobic interior. The branched chain of leucine also makes it important for muscle growth and metabolism. Leucine is one of the three branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) that bodybuilders and athletes prize for their anabolic effects.

Leucine has a strong tendency to form both alpha helices and beta sheets. This structural versatility makes it a common component of performance peptides and proteins involved in signaling and metabolism.

How many peptide bonds? The fundamental counting principle

Here is the question that probably brought you to this page. How many peptide bonds does alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine have?

The answer is four.

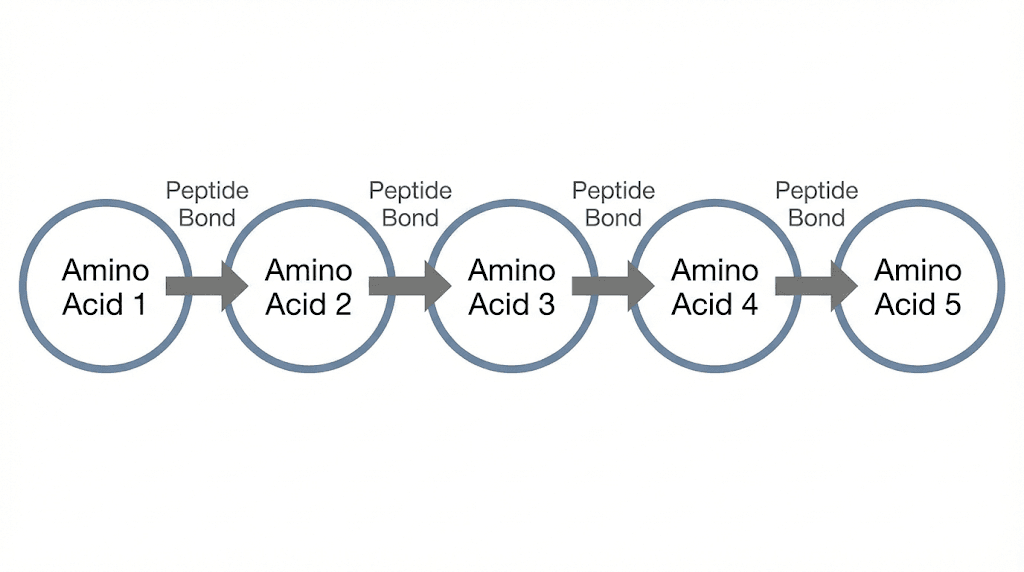

The formula is beautifully simple. Number of peptide bonds equals number of amino acids minus one. Five amino acids minus one equals four peptide bonds. This relationship holds for every peptide ever synthesized, from the smallest dipeptide to the largest protein.

Why the formula works

Think about how peptides form. You start with two amino acids. When they join, one peptide bond forms. You now have a dipeptide. Add a third amino acid, and you create one more peptide bond. Now you have a tripeptide with two peptide bonds.

The pattern continues. Each new amino acid added to the chain creates exactly one new peptide bond. So if you start with n amino acids and link them all together, you end up with n-1 peptide bonds. The first amino acid does not need a bond on its amino side. The last does not need a bond on its carboxyl side. Every connection in between requires exactly one peptide bond.

This principle applies to BPC-157 and TB-500 peptides used for healing. It applies to CJC-1295 used for growth hormone release. It applies to insulin with its 51 amino acids and 50 peptide bonds. Universal and reliable.

The specific bonds in alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine

Let us trace the bonds in our pentapeptide:

Bond 1 connects alanine to glutamic acid (Ala-Glu).

Bond 2 connects glutamic acid to glycine (Glu-Gly).

Bond 3 connects glycine to alanine (Gly-Ala).

Bond 4 connects alanine to leucine (Ala-Leu).

Four bonds. Four connections. Four places where water was released during synthesis. Four locations where the chain can be cleaved by hydrolysis.

The chemistry of peptide bond formation

Understanding how peptide bonds form reveals why they have the properties they do. The process is elegant. It is also energetically demanding, which is why cells invest so much machinery in peptide synthesis.

Dehydration synthesis: building bonds by removing water

Peptide bond formation is a condensation reaction, also called dehydration synthesis. The carboxyl group of one amino acid reacts with the amino group of another. During this reaction, a water molecule is released.

Specifically, the hydroxyl group (OH) from the carboxyl group and a hydrogen from the amino group combine to form water (H2O). What remains is a covalent bond between the carbon of the first amino acid and the nitrogen of the second. This carbon-nitrogen linkage is the peptide bond.

The bond that forms is an amide bond, specifically a secondary amide. The resulting structure has the formula -CO-NH-, where CO is the carbonyl group and NH is the secondary amine. This linkage is sometimes called a peptide linkage or amide linkage interchangeably.

Energy requirements

The formation of peptide bonds requires energy input. The equilibrium of the reaction actually favors hydrolysis, the breaking of peptide bonds, rather than synthesis. In living cells, this thermodynamic obstacle is overcome through coupling to ATP hydrolysis.

Ribosomes, the cellular machines that synthesize proteins, use the energy stored in aminoacyl-tRNA molecules to drive peptide bond formation. The process is remarkably efficient. Cells can synthesize proteins with hundreds of amino acids in seconds to minutes.

In laboratory settings, peptide synthesis requires careful chemistry to activate carboxyl groups and protect amino groups. The peptide testing labs that verify peptide purity understand these synthetic challenges intimately.

The remarkable stability of peptide bonds

Once formed, peptide bonds are remarkably stable. They resist heating and high salt concentrations. The half-life of a peptide bond in water at 25 degrees Celsius ranges from 350 to 600 years. This extraordinary stability is why proteins can maintain their structure and function over biologically relevant timescales.

Breaking peptide bonds requires either strong acid or base under harsh conditions, or the catalytic action of enzymes called proteases or peptidases. These enzymes lower the activation energy for hydrolysis, allowing controlled breakdown of peptides when needed.

The hydrolysis of peptide bonds releases 8 to 16 kJ/mol of Gibbs free energy. This relatively small energy release explains why the reverse reaction, synthesis, requires significant energy input.

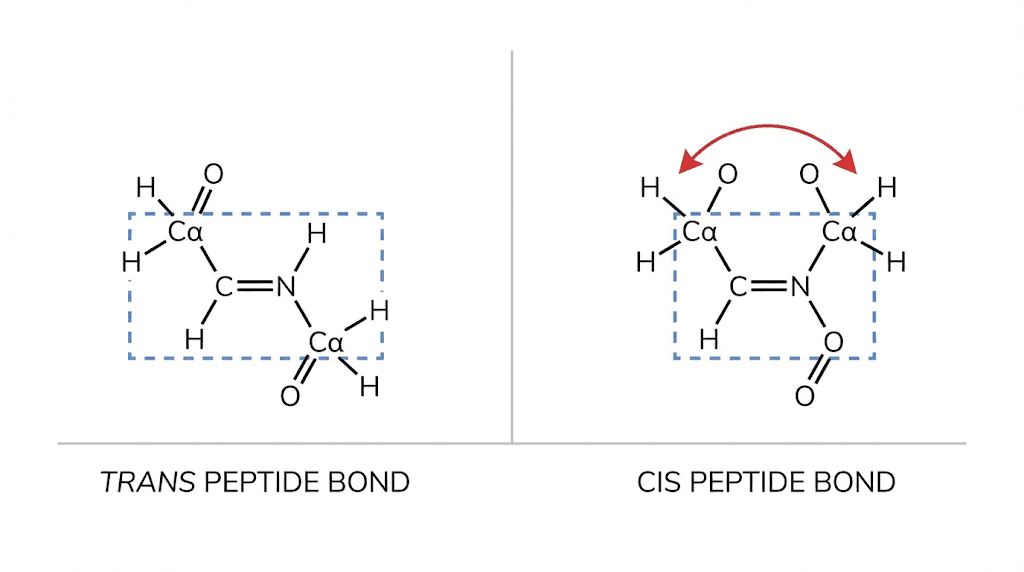

Understanding the partial double bond character of peptide bonds

Peptide bonds are not simple single bonds. They have approximately 40 percent double bond character due to resonance. This property has profound implications for peptide structure and function.

Resonance and electron delocalization

In a peptide bond, the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom can delocalize into the carbonyl group. This electron sharing creates two resonance structures. In one, the bond between carbon and nitrogen is a single bond, and the bond between carbon and oxygen is a double bond. In the other, negative charge resides on oxygen, positive charge resides on nitrogen, and the carbon-nitrogen bond has double bond character.

The actual structure is a hybrid of these resonance forms. Electrons are shared between the nitrogen and oxygen atoms. The carbon-nitrogen bond is shorter than a typical single bond (0.132 nm versus the usual 0.147 nm for a carbon-nitrogen single bond). The carbon-oxygen bond is longer than a typical double bond.

Planarity and rigidity

The partial double bond character has a critical consequence. Rotation around the peptide bond is restricted. The six atoms of the peptide group, the carbonyl carbon, the oxygen, the nitrogen, the hydrogen on nitrogen, and the two adjacent alpha carbons, all lie in the same plane.

This planarity and rigidity mean that peptide bonds cannot twist freely. They exist in either cis or trans configurations, similar to the geometric isomers around true double bonds. In proteins, the trans configuration dominates overwhelmingly, with a ratio of roughly 1000:1 over the cis form.

The rigidity of peptide bonds is essential for protein folding. Because each peptide bond constrains the backbone geometry, the chain can only adopt certain conformations. This restriction paradoxically makes folding more efficient by limiting the conformational space that must be searched.

The trans configuration preference

Why does trans dominate over cis? The answer is steric hindrance. In the cis configuration, the bulky groups attached to the alpha carbons on either side of the peptide bond end up on the same side. They clash with each other. In the trans configuration, these groups are on opposite sides, minimizing steric strain.

The only common exception involves proline. Because proline's side chain connects back to the backbone nitrogen, forming a ring, the energy difference between cis and trans is smaller. About 6 percent of peptide bonds preceding proline adopt the cis configuration, compared to 0.1 percent for other amino acids.

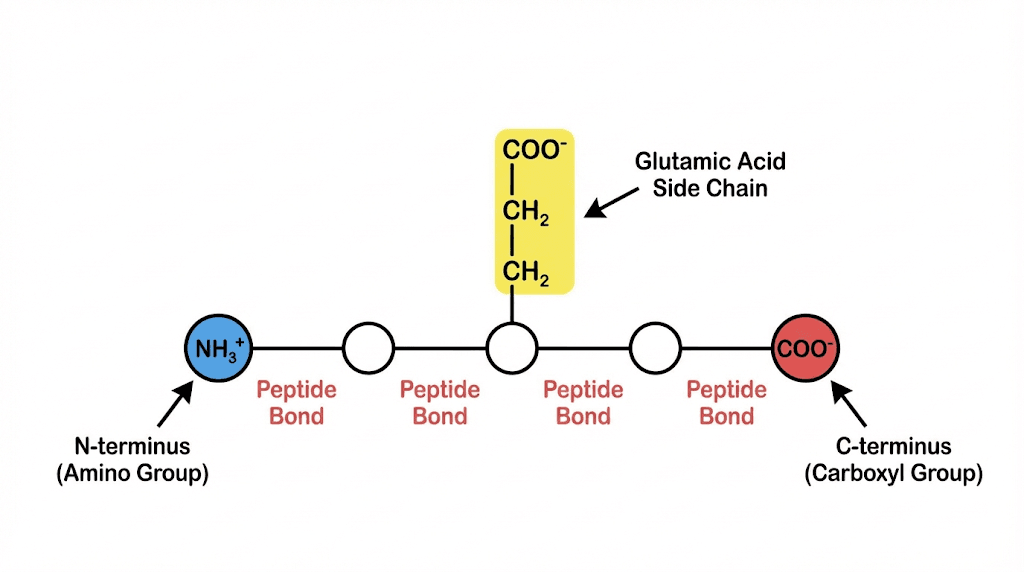

The N-terminus and C-terminus of alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine

Every peptide has two ends with distinct chemical properties. Understanding these termini is fundamental to working with peptides in any form.

The N-terminus: where alanine begins

The N-terminus, also called the amino terminus, is where the peptide chain begins. In alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine, the N-terminal amino acid is alanine. This alanine has a free amino group (NH2 or NH3+ at physiological pH) that is not involved in any peptide bond.

The free amino group at the N-terminus carries a positive charge under physiological conditions. This charge contributes to the overall electrostatic properties of the peptide and can influence how it interacts with solutions, membranes, and other molecules.

In protein synthesis, the N-terminus is where construction begins. The ribosome assembles proteins from N-terminus to C-terminus, adding one amino acid at a time to the growing chain. This directionality is universal across all domains of life.

The C-terminus: where leucine ends

The C-terminus, also called the carboxyl terminus, is where the peptide chain ends. In our pentapeptide, leucine occupies this position. The leucine has a free carboxyl group (COOH or COO- at physiological pH) that has not formed a peptide bond.

This free carboxyl group carries a negative charge under physiological conditions. Combined with the positive charge at the N-terminus, this creates a dipole across the peptide. The molecule has a positively charged end and a negatively charged end.

But remember, alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine has two carboxyl groups, not one. The second carboxyl group belongs to the side chain of glutamic acid. This additional negative charge significantly affects the peptide's behavior in solution.

Functional implications of the termini

The termini of peptides often carry important functional information. In living cells, the N-terminus frequently contains targeting signals that direct proteins to specific locations. The C-terminus can contain retention signals that keep proteins in particular organelles.

For therapeutic peptides, modifications at the termini can dramatically affect stability, activity, and half-life. Acetylation of the N-terminus or amidation of the C-terminus are common modifications that protect against degradation by exopeptidases.

Counting functional groups: carboxyls and amino groups

Alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine has specific functional groups that determine its chemical behavior. Let us count them carefully.

How many carboxyl groups?

The pentapeptide has two carboxyl groups. One belongs to the C-terminal leucine, the standard free carboxyl group that every peptide has at its C-terminus. The second belongs to the side chain of glutamic acid.

If you are asked on an exam how many free carboxyl groups this peptide has, the answer is two. Both are capable of donating protons, both carry negative charges at physiological pH, and both contribute to the peptide's acidic character.

Contrast this with a pentapeptide that lacks acidic amino acids. Ala-Gly-Gly-Gly-Leu, for example, would have only one carboxyl group. The presence of glutamic acid doubles the carboxyl count in our specific sequence.

How many amino groups?

The pentapeptide has one free amino group, located at the N-terminus on the first alanine. This is the standard arrangement. Every simple linear peptide has exactly one free amino group at its N-terminus.

Why not more? Because the amino groups of the internal amino acids are all tied up in peptide bonds. The nitrogen of each internal residue is bonded to the carbonyl carbon of the preceding residue. Only the N-terminal nitrogen remains free.

If you had a peptide containing lysine, you would gain an additional free amino group from the lysine side chain. Our pentapeptide lacks lysine, so it has only the single N-terminal amino group.

No disulfide bridges

Disulfide bridges form between cysteine residues when their thiol groups oxidize and link together. These bridges can stabilize peptide and protein structure dramatically.

Alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine contains no cysteine. Therefore, it cannot form disulfide bridges. The sequence Ala-Glu-Gly-Ala-Leu has no sulfur-containing amino acids at all.

This absence affects the peptide's potential for crosslinking and structural stabilization. Peptides with disulfide bridges often have more rigid structures and greater resistance to denaturation. Without cysteines, our pentapeptide relies entirely on its backbone and non-covalent interactions for whatever structure it adopts.

Peptide classification: oligopeptides, polypeptides, and proteins

Where does alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine fit in the classification of peptides? Understanding these categories helps you communicate precisely about different types of peptides.

Oligopeptides: the short chains

Oligopeptides are short peptides, typically containing 2 to 20 amino acids depending on which definition you use. Some sources draw the line at 10 amino acids, others at 15 or 20. The prefix "oligo" means "few."

Our pentapeptide falls squarely in the oligopeptide category. With five amino acids, it is solidly in the short range. Other examples of oligopeptides include dipeptides (2 amino acids), tripeptides (3 amino acids), tetrapeptides (4 amino acids), and hexapeptides (6 amino acids).

Many bioactive peptides used in skincare and copper peptides like GHK-Cu are oligopeptides. Their small size allows them to penetrate tissues and exert effects that larger molecules cannot achieve.

Polypeptides: the longer chains

Polypeptides are longer chains, typically defined as containing more than 10, 20, or 50 amino acids depending on the source. The prefix "poly" means "many." Polypeptides are single continuous chains that may or may not fold into functional units on their own.

BPC-157, with its 15 amino acids, sits right at the boundary between oligopeptide and polypeptide definitions. TB-500, derived from a larger thymosin beta-4 sequence, represents a longer polypeptide.

Proteins: functional units

Proteins are typically defined as polypeptides with more than 50 to 100 amino acids, though function matters as much as size. A protein is a polypeptide (or combination of polypeptides) that folds into a specific three dimensional structure and performs a biological function.

Insulin, with its 51 amino acids arranged in two chains connected by disulfide bridges, is often considered the smallest protein. Titin, the largest known protein, contains over 34,000 amino acids. The range is enormous.

Our pentapeptide is far too small to be considered a protein. It lacks the complexity needed for sophisticated biological functions. But understanding its chemistry provides the foundation for understanding how larger peptide hormones and proteins work.

Secondary structure potential of alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine

While our pentapeptide is too short to form stable secondary structures, the amino acids it contains have definite preferences that would matter in longer sequences.

Alpha helix propensity

Alanine, glutamic acid, and leucine all have strong tendencies to form alpha helices. If you were to extend our sequence into a longer polypeptide with repeated Ala-Glu-Leu motifs, you might expect significant helix formation.

The alpha helix is a right-handed coil stabilized by hydrogen bonds between carbonyl oxygens and amide hydrogens four residues apart. Each turn contains 3.6 residues. The stability of peptide structure depends heavily on these hydrogen bonding patterns.

Glycine disrupts helices

Glycine, however, disrupts helices. Its flexibility allows conformations that break the regular helical pattern. In our pentapeptide, the glycine at position three might prevent helix formation even if the sequence were extended.

This is not necessarily bad. Flexibility has its uses. In longer proteins, glycine often appears at hinge regions where movement is needed. The collagen triple helix requires glycine at every third position precisely because of its small size and flexibility.

Beta sheet tendencies

Leucine, valine, isoleucine, and other branched chain amino acids have strong tendencies to form beta sheets. The extended conformation of beta strands maximizes space for bulky side chains.

In a longer peptide containing our sequence, the leucine might participate in beta sheet formation if the sequence context allowed. Beta sheets form when extended strands align side by side, connected by hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms.

Calculating molecular weight and other properties

Knowing the sequence allows you to calculate various properties of the peptide. These calculations matter for laboratory work and for understanding peptide dosing.

Molecular weight calculation

To calculate molecular weight, you add the masses of the individual amino acids, then subtract 18 Da for each peptide bond (accounting for the water molecules lost during bond formation).

Alanine: 89.09 Da

Glutamic acid: 147.13 Da

Glycine: 75.07 Da

Alanine: 89.09 Da

Leucine: 131.17 Da

Sum: 531.55 Da

Subtract 4 times 18.02 Da for the four peptide bonds: 72.08 Da

Approximate molecular weight: 459.47 Da

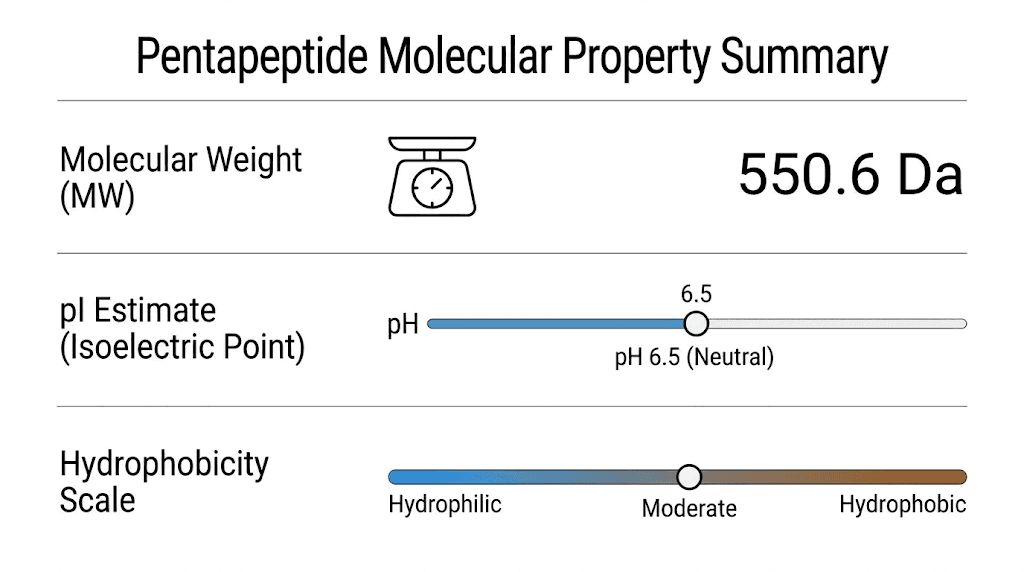

This calculation gives you a ballpark figure. The exact value depends on isotope distribution and whether you count the molecular ion or the average mass. For most practical purposes, alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine has a molecular weight around 460 Da.

Isoelectric point considerations

The isoelectric point (pI) is the pH at which a molecule carries no net charge. For our pentapeptide, the presence of the N-terminal amino group (basic), the C-terminal carboxyl group (acidic), and the glutamic acid side chain (acidic) all contribute.

With two acidic groups and one basic group, we would expect the pI to be acidic, somewhere below pH 7. The exact value requires calculation using the pKa values of each ionizable group. For peptides with more acidic residues than basic ones, the pI typically falls in the range of 3 to 5.

Understanding pI matters when you are working with peptide solutions and need to predict solubility or choose appropriate buffer conditions.

Hydrophobicity assessment

Is our pentapeptide hydrophobic or hydrophilic? The answer is mixed, as is often the case with peptides.

Alanine and leucine are hydrophobic, preferring to avoid water. Glycine is essentially neutral, too small to have strong preferences. Glutamic acid is hydrophilic, with its charged side chain strongly attracting water.

The overall character depends on which residues dominate. With two alanines, one leucine, one glycine, and one glutamic acid, the peptide has significant hydrophobic character but also substantial hydrophilicity from the glutamic acid and the charged termini. It would likely be somewhat soluble in water, more so than a purely hydrophobic pentapeptide.

Practical applications of understanding peptide structure

This foundational knowledge of peptide chemistry has practical applications across multiple fields. Whether you are studying for an exam, working in a research lab, or exploring peptide therapy, these concepts matter.

Biochemistry education

Questions about alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine appear frequently on biochemistry exams because the pentapeptide illustrates multiple concepts simultaneously. Instructors can ask about bond counting, functional group identification, nomenclature, and structural properties all from a single sequence.

The formula n-1 for peptide bonds is worth memorizing. The principles of N-terminus and C-terminus orientation apply to every sequence you will encounter. The effects of individual amino acids on structure scale up to full proteins.

Laboratory peptide work

When synthesizing or analyzing peptides in the laboratory, you need to know what you are making and what you expect to see. Mass spectrometry will show peaks corresponding to molecular weight. Chromatography behavior depends on hydrophobicity. Solubility depends on charge and polarity.

If you are working with peptide reconstitution, understanding chemistry helps you choose appropriate solvents and storage conditions. Water works for hydrophilic peptides. You might need DMSO or other solvents for hydrophobic sequences.

Understanding therapeutic peptides

The therapeutic peptides used in medicine and research follow the same chemical principles as our model pentapeptide. BPC-157 dosing, sermorelin applications, and ipamorelin effects all depend on the same fundamental chemistry.

Knowing how peptide bonds form and break helps you understand stability. Knowing about termini and functional groups helps you understand modifications that improve therapeutic properties. The foundation we have built with alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine applies broadly.

Peptide bond hydrolysis and digestion

What happens when peptide bonds break? The reverse of synthesis is hydrolysis, and understanding this process matters for digestion, degradation, and laboratory applications.

The hydrolysis reaction

Hydrolysis literally means "breaking with water." A water molecule adds across the peptide bond, regenerating the original amino and carboxyl groups. The products are the individual amino acids or shorter peptide fragments.

As mentioned earlier, this reaction is thermodynamically favorable but kinetically slow. Without catalysis, peptide bonds last centuries. Enzymes called proteases or peptidases speed this reaction enormously.

Digestive proteases

When you eat protein, your digestive system must break it down into absorbable units. Pepsin in the stomach, trypsin and chymotrypsin in the small intestine, and various other proteases work together to hydrolyze proteins into amino acids and small peptides.

Different proteases have different specificities. Trypsin cuts after lysine and arginine. Chymotrypsin cuts after aromatic amino acids. This specificity determines how proteins are dismantled.

For alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine, specific enzymes could cleave at specific positions. Without lysine, arginine, or aromatic residues, this particular pentapeptide would not be a good substrate for trypsin or chymotrypsin. Other proteases with different specificities would be needed.

Laboratory hydrolysis

In the laboratory, peptide bonds can be hydrolyzed using strong acid (typically 6M HCl at 110 degrees Celsius for 24 hours) or specific enzymes. Acid hydrolysis releases all amino acids but destroys some, particularly tryptophan. Enzymatic hydrolysis is gentler but may not cleave all bonds completely.

These techniques matter for amino acid analysis, where you need to determine the composition of an unknown peptide. By completely hydrolyzing the sample and measuring the released amino acids, you can determine what building blocks are present and in what ratios.

Extending the concept: from pentapeptides to proteins

Everything we have learned about alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine scales up. The principles that govern a five residue peptide govern proteins with thousands of residues.

Scaling the bond counting formula

A protein with 100 amino acids has 99 peptide bonds. A protein with 500 amino acids has 499 peptide bonds. The formula never changes. n amino acids means n-1 peptide bonds, whether n is 5 or 5000.

This scalability makes peptide chemistry elegant. Once you understand the fundamentals, you can work with sequences of any length. The complexity increases, but the underlying chemistry remains constant.

How sequence determines structure

In proteins, the amino acid sequence determines everything. The sequence dictates how the chain folds, what secondary structures form, how different parts of the protein interact, and ultimately what functions the protein can perform.

Our pentapeptide is too short for complex folding. But if we embedded its sequence in a larger protein, the alanines might participate in helices, the glycine might form a turn, and the leucine might pack into a hydrophobic core. Sequence is destiny in the protein world.

Understanding these relationships helps when analyzing bioregulator peptides that interact with specific cellular targets. The sequence determines the shape, and the shape determines the function.

From simple to complex

The journey from understanding a pentapeptide to understanding the proteome is one of increasing complexity but not different principles. The same bonds, the same atoms, the same forces govern everything from simple sequences to the most sophisticated molecular machines.

Researchers at SeekPeptides help members understand these connections. When you grasp how a simple sequence like alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine works, you are better equipped to understand the longevity peptides, fat loss peptides, and healing peptides that build on these foundations.

Common exam questions about peptide structure

If you are studying for an exam, you will likely encounter questions about sequences like alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine. Here are the types of questions to expect and how to answer them.

How many peptide bonds?

The answer is always the number of amino acids minus one. For alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine with five amino acids, the answer is four.

Some questions try to trip you up by including decoy answers like five (the number of amino acids) or six (one more than amino acids). Do not fall for these. The formula is reliable and applies universally.

How many amino acids?

Count the parts of the name. Alanyl is one. Glutamyl is two. Glycyl is three. Alanyl is four. Leucine is five. The answer is five amino acids.

Remember that the last amino acid does not have the "yl" suffix because it is not bonded to anything on its carboxyl side. The naming convention tells you exactly how many residues are present.

How many free carboxyl groups?

For alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine, the answer is two. One at the C-terminus on leucine, one on the side chain of glutamic acid.

Questions might ask about "free" or "total" carboxyl groups. The carboxyl groups involved in peptide bonds are no longer free, they have been converted to amides. Only the ones not involved in peptide bonds count.

How many free amino groups?

For this pentapeptide, the answer is one. The free amino group is at the N-terminus on the first alanine.

If the sequence contained lysine, you would add one for the lysine side chain amino group. Without lysine, there is only the N-terminal amino group.

Does it have disulfide bridges?

No. Disulfide bridges require cysteine residues, and alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine contains no cysteines. The sequence Ala-Glu-Gly-Ala-Leu lacks sulfur entirely.

Applying this knowledge to research peptides

The peptides used in research and therapeutic applications follow the same rules as our model pentapeptide. Understanding structure helps you work with any peptide more effectively.

Reading peptide specifications

When you purchase a research peptide, the specifications will include the sequence. Now you can interpret that sequence. You know how many peptide bonds it contains. You know what the termini look like. You can estimate molecular weight and predict solubility.

Quality peptide suppliers provide certificates of analysis showing purity and identity. Understanding peptide chemistry helps you evaluate these documents critically. Mass spectrometry data should match predicted molecular weights. HPLC profiles should reflect expected properties.

Storage considerations

Peptide stability depends on chemical properties. Storage temperature, reconstitution conditions, and long-term preservation all depend on understanding the underlying chemistry.

Peptide bonds are stable, but other reactions can degrade peptides. Oxidation of methionine, deamidation of asparagine, aggregation through hydrophobic interactions. Knowing the sequence helps predict which degradation pathways matter.

Dosing and bioavailability

Molecular weight affects dosing calculations. A peptide calculator helps convert between mass and molar concentrations, but you need to know the molecular weight first. Understanding how to calculate weight from sequence gives you that foundation.

Bioavailability depends on how the peptide interacts with biological barriers. Hydrophobic peptides cross membranes more easily. Charged peptides may need special delivery mechanisms. The amino acid composition tells you what to expect.

Frequently asked questions

What is the sequence of alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine?

The sequence is Ala-Glu-Gly-Ala-Leu using three letter codes, or AEGSL using single letter codes. The peptide starts with alanine at the N-terminus and ends with leucine at the C-terminus. The sequence contains five amino acids arranged in this specific order, with alanine appearing twice in positions one and four.

How do you count peptide bonds in any peptide?

The formula is simple and universal. Take the number of amino acids and subtract one. A dipeptide with two amino acids has one peptide bond. A tripeptide has two. A pentapeptide like alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine has four peptide bonds. This formula works for any length peptide or protein.

Why does glutamic acid give the peptide two carboxyl groups?

Glutamic acid has a carboxyl group in its side chain in addition to the standard backbone carboxyl group. In our pentapeptide, the backbone carboxyl of glutamic acid is involved in the peptide bond to glycine. But the side chain carboxyl remains free. Combined with the C-terminal carboxyl on leucine, this gives two free carboxyl groups total.

Is alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine an oligopeptide or polypeptide?

It is an oligopeptide. With five amino acids, it falls in the short peptide category. Oligopeptides are generally defined as peptides with 2 to 20 amino acids. Polypeptides contain more residues, typically 20 to 50 or more depending on the definition used. Full proteins usually contain more than 50 to 100 amino acids.

What determines whether a peptide bond is cis or trans?

Steric factors primarily determine the configuration. The trans form is favored because it minimizes clashes between bulky groups on either side of the bond. In trans, these groups are on opposite sides. In cis, they would be on the same side and would clash. About 99.9 percent of peptide bonds in proteins are trans. The exception involves proline, where the energy difference between cis and trans is smaller.

Can alanylglutamylglycylalanylleucine form secondary structures?

At five amino acids, the peptide is too short to form stable secondary structures like alpha helices (which typically require at least one complete turn of about 4 residues plus stabilizing hydrogen bonds) or beta sheets (which require extended strands to align). However, the amino acids in the sequence have structural preferences. Alanine, glutamic acid, and leucine favor alpha helices in longer sequences. Glycine tends to disrupt regular structures due to its flexibility.

External resources

For researchers serious about mastering peptide chemistry and applying it to practical protocols, SeekPeptides provides comprehensive resources, calculators, and expert guidance for every level of experience.

In case I do not see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night. May your peptide bonds stay stable, your sequences stay accurate, and your understanding stay comprehensive.