Jan 27, 2026

Your pancreas produces seven distinct peptide hormones. Most people only know two of them. The other five? They control everything from appetite to aging, from fat storage to cognitive function. And understanding how they work together changes how you think about metabolism, weight loss, and longevity.

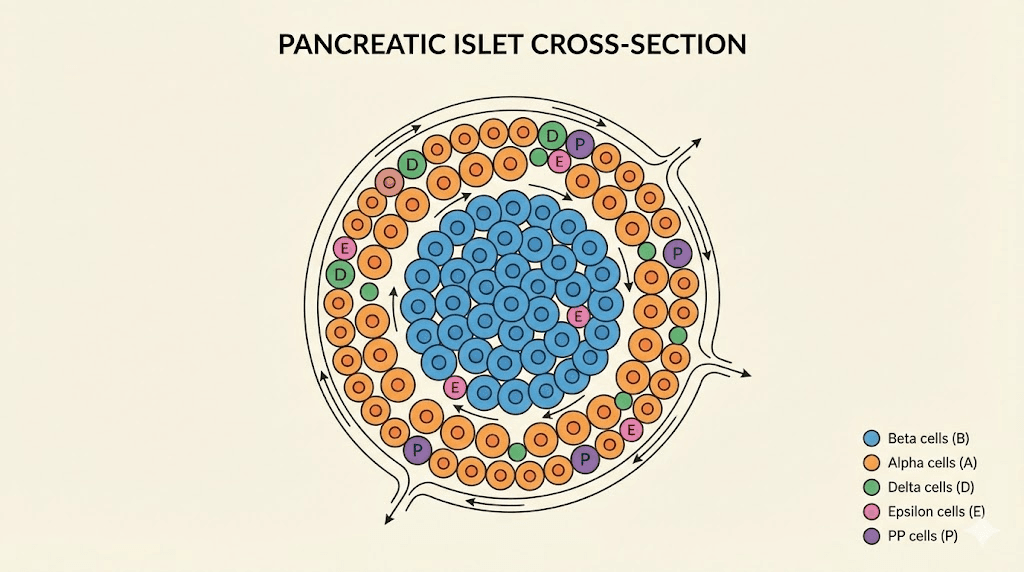

The islets of Langerhans, those tiny clusters scattered throughout your pancreas, contain five different cell types. Each secretes its own peptide hormone. Alpha cells release glucagon. Beta cells produce insulin. Delta cells secrete somatostatin. Epsilon cells make ghrelin. And PP cells generate pancreatic polypeptide. Add in amylin and C-peptide from beta cells, and you have a complex hormonal orchestra that most endocrinology textbooks barely scratch the surface of.

Here is the problem. When one instrument plays out of tune, the entire metabolic symphony suffers. Type 2 diabetes is not just an insulin problem. It involves dysfunction across multiple pancreatic hormones simultaneously. Weight loss resistance often traces back to disrupted satiety signaling from pancreatic polypeptide and amylin. And the longevity research community is increasingly focused on how these hormones influence aging at the cellular level.

This guide covers every pancreatic peptide hormone in depth. You will learn the mechanisms, the clinical applications, and the research implications. Whether you are a researcher exploring peptide therapeutics, a clinician seeking deeper understanding, or simply someone who wants to understand their own metabolism better, this is the comprehensive resource you have been looking for. SeekPeptides created this guide because understanding these fundamental hormones is essential for anyone serious about peptide research.

The pancreatic islets: where peptide hormones originate

The pancreas serves dual functions. Its exocrine portion produces digestive enzymes. Its endocrine portion, the islets of Langerhans, synthesizes hormones that regulate metabolism throughout the body. These islets comprise only 1-2% of pancreatic mass, yet they contain approximately one million hormone-producing cell clusters in the average adult.

Each islet contains five distinct cell types arranged in a specific architecture. Beta cells dominate, accounting for 65-80% of islet mass. They cluster in the core. Alpha cells form about 15-20% and typically position at the periphery in rodents, though human islets show more intermingled arrangements. Delta cells comprise less than 10%. Epsilon cells and PP cells make up the smallest populations.

This arrangement matters.

Hormones released from one cell type directly influence neighboring cells through paracrine signaling. Insulin from beta cells suppresses glucagon release from alpha cells. Somatostatin from delta cells inhibits both insulin and glucagon secretion. The physical proximity enables rapid, precise metabolic adjustments that could not occur through systemic circulation alone.

Blood flow through the islets follows a specific pattern as well. In many species, blood enters through arterioles in the beta cell core and flows outward past alpha and delta cells. This means insulin bathes alpha cells before glucagon reaches systemic circulation. The implications for peptide therapy development are significant because disrupting this local environment affects hormone balance in ways that systemic administration cannot replicate.

Insulin: the master metabolic regulator

Insulin is the most studied pancreatic peptide hormone. It controls glucose uptake, protein synthesis, and fat storage. Without it, cells starve amid plenty. With too much, hypoglycemia becomes life-threatening. The balance is everything.

Structure and synthesis

Beta cells produce insulin as a precursor called preproinsulin, a 110-amino acid chain. Signal peptidase cleaves the signal sequence, yielding proinsulin. Then prohormone convertases remove the C-peptide connecting segment, leaving the mature insulin molecule with its A-chain and B-chain linked by two disulfide bonds.

This processing occurs within secretory granules. Both insulin and C-peptide are stored together and released in equimolar amounts. This is why C-peptide measurement serves as a reliable marker of endogenous insulin production, since injected insulin does not contain C-peptide.

Mature human insulin contains 51 amino acids total: 21 in the A-chain and 30 in the B-chain. Its molecular weight is approximately 5,800 daltons. The three-dimensional structure includes alpha-helical regions that are essential for receptor binding.

Secretion mechanisms

Glucose is the primary trigger for insulin release. When blood glucose rises, glucose transporters (primarily GLUT2 in rodents, GLUT1 and GLUT3 in humans) move glucose into beta cells. Glucokinase phosphorylates glucose to glucose-6-phosphate, initiating glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism. The resulting increase in ATP/ADP ratio closes ATP-sensitive potassium channels.

Channel closure depolarizes the cell membrane. Voltage-gated calcium channels open. Calcium influx triggers exocytosis of insulin-containing granules. This is called the triggering pathway.

But glucose also amplifies insulin secretion through ATP-independent mechanisms. This amplifying pathway involves metabolic signals that enhance exocytosis beyond what calcium influx alone would produce. The mechanisms include changes in the ratio of long-chain acyl-CoAs, glutamate accumulation, and NADPH generation.

Incretin hormones significantly potentiate glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. GLP-1 and GIP from the gut bind to receptors on beta cells, increasing cAMP and enhancing both triggering and amplifying pathways. This explains why oral glucose produces greater insulin release than intravenous glucose, a phenomenon called the incretin effect that accounts for up to 60% of postprandial insulin secretion.

Metabolic actions

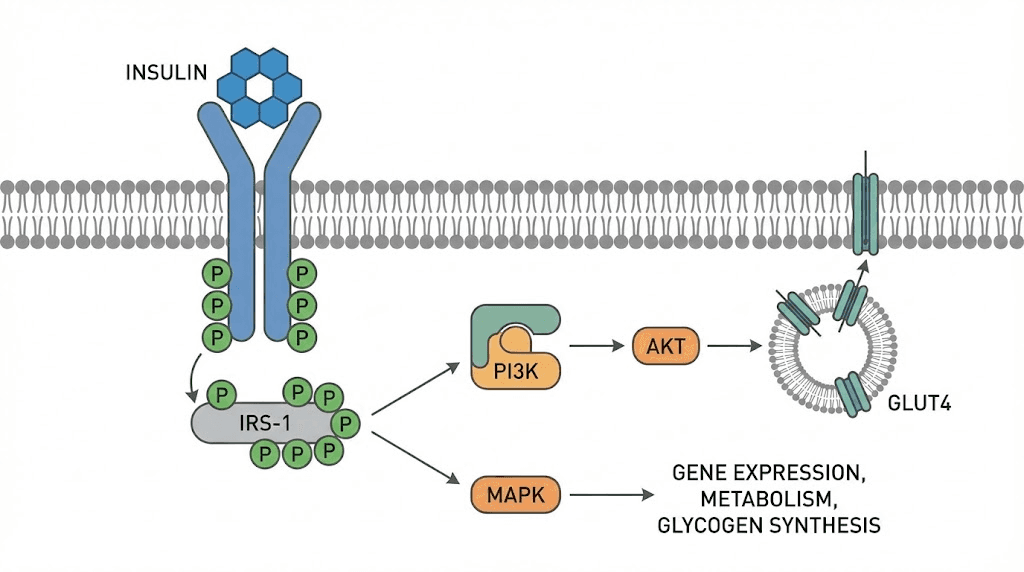

Insulin binding to its receptor activates a tyrosine kinase cascade. Insulin receptor substrates are phosphorylated. Downstream signaling through PI3K and Akt pathways produces the characteristic metabolic effects.

In muscle and adipose tissue, insulin stimulates translocation of GLUT4 transporters to the cell surface. Glucose uptake increases dramatically. In liver, insulin suppresses gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis while promoting glycogen synthesis and lipogenesis.

Protein metabolism shifts toward anabolism. Insulin promotes amino acid uptake and protein synthesis while inhibiting proteolysis. For researchers interested in muscle growth peptides, understanding insulin signaling provides essential context for how various peptides interact with anabolic pathways.

Lipid metabolism responds strongly to insulin as well. The hormone promotes fatty acid synthesis in liver, stimulates lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue to facilitate fat storage, and suppresses lipolysis. This is why insulin resistance often accompanies elevated free fatty acid levels and dyslipidemia.

Clinical significance

Type 1 diabetes results from autoimmune destruction of beta cells. Insulin production fails completely. Without exogenous insulin replacement, the condition is fatal.

Type 2 diabetes involves both insulin resistance and progressive beta cell dysfunction. Initially, beta cells compensate by producing more insulin. Eventually, they cannot keep pace. Hyperglycemia develops. The GLP-1 agonists now widely used for diabetes and weight loss work partly by enhancing insulin secretion from remaining beta cells.

Insulinomas are rare tumors of beta cells that cause excessive insulin secretion and dangerous hypoglycemia. Diagnosis involves demonstrating inappropriately elevated insulin and C-peptide during hypoglycemia. Treatment is surgical removal.

For those exploring peptide therapy, understanding insulin dynamics is fundamental. Many peptides either directly or indirectly affect insulin sensitivity, secretion, or action.

Glucagon: the counter-regulatory hormone

If insulin is the storage hormone, glucagon is the mobilization hormone. It prevents hypoglycemia by stimulating hepatic glucose production. The balance between these two peptides maintains blood glucose within the narrow range required for survival.

Structure and synthesis

Alpha cells produce glucagon from proglucagon, a 160-amino acid precursor. However, the same proglucagon gene is expressed in intestinal L-cells, where different processing produces GLP-1 and GLP-2 instead of glucagon. This tissue-specific processing depends on which prohormone convertases are expressed.

Mature glucagon contains 29 amino acids with a molecular weight of approximately 3,500 daltons. It circulates as a single peptide chain without disulfide bonds, making it relatively susceptible to degradation.

Secretion regulation

Low blood glucose stimulates glucagon release. This counter-regulatory response prevents dangerous hypoglycemia during fasting or between meals.

But glucagon secretion is also controlled by paracrine signals from neighboring beta and delta cells. Insulin directly suppresses glucagon release from alpha cells. Somatostatin does the same. In type 1 diabetes, the loss of local insulin signaling contributes to inappropriate glucagon secretion, which worsens hyperglycemia.

Amino acids, particularly arginine and alanine, stimulate glucagon secretion. This makes physiological sense because amino acid metabolism requires gluconeogenic substrates, and glucagon promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis.

Autonomic nervous system input affects glucagon release as well. Sympathetic activation during stress or exercise increases glucagon to mobilize glucose for fight-or-flight responses.

Metabolic actions

Glucagon binds to G-protein coupled receptors primarily in the liver. Receptor activation increases cAMP, activating protein kinase A. This stimulates glycogenolysis, the breakdown of glycogen to release glucose. It also promotes gluconeogenesis, the synthesis of new glucose from amino acids, lactate, and glycerol.

The net effect is increased hepatic glucose output. Blood glucose rises.

Glucagon also affects lipid metabolism. It promotes lipolysis in adipose tissue, releasing fatty acids for energy. In liver, it stimulates ketogenesis when glucose is scarce, producing ketone bodies that brain and muscle can use for fuel.

The hormone has minimal direct effects on muscle because skeletal muscle lacks glucagon receptors. This targeting specificity is important for maintaining blood glucose without directly affecting peripheral glucose utilization.

Clinical relevance

Glucagon is used clinically as an emergency treatment for severe hypoglycemia. Injectable glucagon kits allow rapid reversal of insulin-induced hypoglycemia when the patient cannot eat.

In type 2 diabetes, glucagon secretion is often inappropriately elevated despite hyperglycemia. This glucagon dysregulation contributes significantly to fasting hyperglycemia. Some newer diabetes medications, including dual GLP-1/glucagon receptor agonists, attempt to modulate both pathways simultaneously.

Glucagonomas are rare alpha cell tumors that cause a distinctive syndrome including diabetes, weight loss, and a characteristic rash called necrolytic migratory erythema. Plasma glucagon levels are markedly elevated.

For researchers studying fat loss peptides, glucagon signaling pathways are relevant because glucagon promotes lipolysis and increases energy expenditure.

Pancreatic polypeptide: the satiety signal

Pancreatic polypeptide does not get the attention it deserves. This 36-amino acid hormone plays crucial roles in appetite regulation, gastrointestinal function, and glucose homeostasis. Its potential as a therapeutic target for obesity and diabetes remains largely unexplored.

Structure and source

PP cells, also called F cells, produce pancreatic polypeptide. These cells concentrate in the head of the pancreas but also appear in smaller numbers throughout the islets. PP belongs to the neuropeptide Y family, sharing structural homology with NPY and peptide YY.

The 36-amino acid peptide folds into a hairpin structure stabilized by a polyproline helix. This PP-fold motif is characteristic of the entire NPY family and is essential for receptor binding.

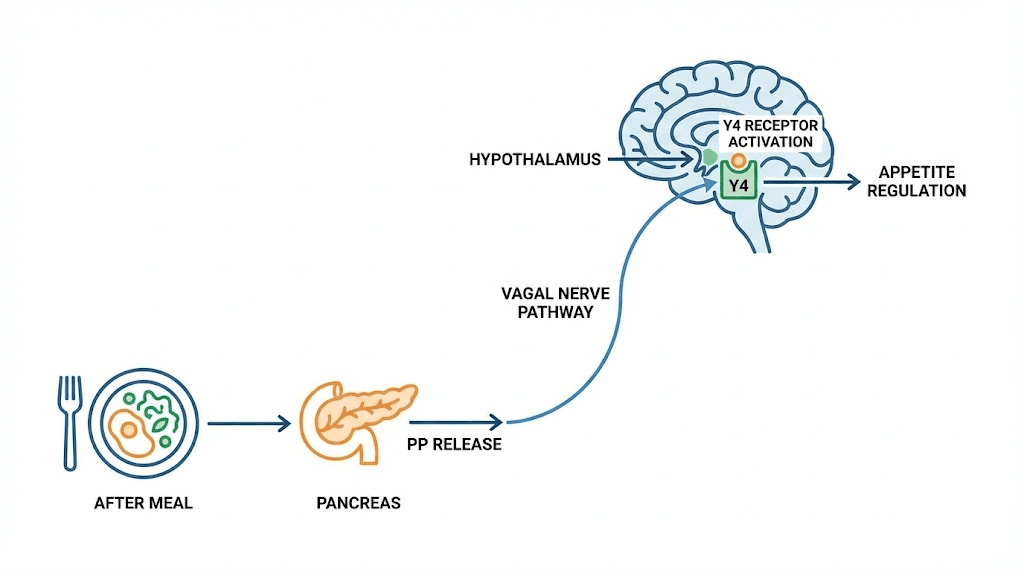

Secretion patterns

Meal ingestion powerfully stimulates PP release. Levels rise within minutes of eating and remain elevated for 4-6 hours. The vagus nerve is the major mediator of postprandial PP secretion. Vagotomy or atropine administration abolishes the meal-induced PP response.

Protein meals produce stronger PP responses than carbohydrate or fat meals. This may relate to the hormone's role in coordinating digestive processes.

Fasting PP levels are low, typically around 80 pg/ml. After meals, concentrations can rise 8-10 fold. The magnitude and duration of the PP response correlate with meal size and caloric content.

Mechanism of action

PP binds primarily to Y4 receptors, which are G-protein coupled receptors linked to inhibitory Gi proteins. Receptor activation decreases cAMP production. Y4 receptors are expressed in pancreas, colon, small intestine, and several brain regions including the hypothalamus.

In the brain, PP accesses the hypothalamus and activates Y4 receptors in the arcuate nucleus. This reduces expression of orexigenic neuropeptides like NPY and AgRP while promoting anorexigenic signaling. The result is decreased appetite and food intake.

Physiological functions

The satiety effect of PP is well-documented. Peripheral PP infusion reduces food intake in both rodents and humans. In one study, PP infusion decreased cumulative 24-hour energy intake by approximately 25%. The effect is sustained, not just a transient suppression.

PP also affects gastrointestinal motility. It slows gastric emptying, prolonging the feeling of fullness after meals. It inhibits gallbladder contraction and pancreatic exocrine secretion, coordinating digestive processes with food intake.

Intriguingly, PP appears to influence hepatic insulin sensitivity. PP deficiency, as seen in chronic pancreatitis, associates with hepatic insulin resistance. PP administration can improve glucose metabolism in these patients.

Therapeutic potential

The satiety-inducing properties of PP make it an attractive target for obesity treatment. However, the peptide has a short plasma half-life of only 6-7 minutes, limiting its direct therapeutic application.

Researchers are developing long-acting PP analogs and Y4 receptor agonists. Stabilized formulations using lipid-based delivery systems show promise for extending PP activity.

PP levels are notably reduced in Prader-Willi syndrome, a condition characterized by insatiable appetite and severe obesity. This deficiency may contribute to the hyperphagia. PP replacement could theoretically help these patients.

For those interested in weight management peptides, understanding PP signaling provides insight into how the body naturally regulates food intake and energy balance.

Somatostatin: the universal inhibitor

Somatostatin earned its nickname as the universal inhibitor for good reason. This peptide suppresses the secretion of numerous hormones throughout the body. In the pancreas, it fine-tunes the balance between insulin and glucagon, preventing excessive swings in either direction.

Forms and distribution

Two bioactive forms exist: somatostatin-14 and somatostatin-28. Both derive from preprosomatostatin through tissue-specific processing. Pancreatic delta cells produce primarily somatostatin-14. Intestinal D cells make more somatostatin-28.

The 14-amino acid form contains a disulfide bridge that creates a cyclic structure essential for biological activity. Somatostatin-28 is an N-terminally extended version with similar receptor binding properties.

Delta cells in the pancreas have a distinctive morphology. They extend long processes that contact many neighboring alpha and beta cells, enabling broad paracrine influence despite their small numbers.

Secretion triggers

Glucose stimulates somatostatin secretion from delta cells. The mechanism involves ATP-sensitive potassium channels, similar to beta cells. High glucose closes these channels, causing depolarization and calcium-dependent exocytosis.

However, somatostatin secretion also depends on paracrine signals. Insulin from beta cells and urocortin 3 promote delta cell activation. Glucagon and GLP-1 from alpha cells also stimulate somatostatin release. This creates feedback loops that modulate hormone secretion in response to local conditions.

Nutrients beyond glucose affect somatostatin as well. Amino acids, particularly arginine, stimulate its release. Fatty acids have variable effects depending on chain length and saturation.

Receptor subtypes and signaling

Five somatostatin receptor subtypes exist: SSTR1 through SSTR5. All are G-protein coupled receptors linked to inhibitory signaling pathways. Different tissues express different receptor profiles.

In pancreatic islets, alpha cells express primarily SSTR2. Beta cells express mainly SSTR3 in mice, though receptor distribution may differ in humans. This differential expression allows somatostatin to exert distinct effects on different cell types.

Receptor activation decreases cAMP production, inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels, and activates potassium channels. These effects hyperpolarize target cells and suppress hormone secretion.

Pancreatic effects

Somatostatin inhibits both insulin and glucagon secretion. The inhibition is powerful, sufficient to suppress hormone release even when other stimulatory signals are present.

This creates a local regulatory mechanism within the islet. When glucose rises, both insulin and somatostatin increase. Somatostatin then dampens insulin secretion, preventing excessive insulin release. Similarly, somatostatin restrains glucagon secretion, coordinating the counterregulatory response.

The delta cell acts as a brake on both major metabolic hormones. This prevents overshoot and helps maintain glucose within normal limits.

Clinical applications

Somatostatin analogs like octreotide and lanreotide are used clinically to treat hormone-secreting tumors. They suppress growth hormone in acromegaly, insulin in insulinomas, and various gut hormones in neuroendocrine tumors.

In diabetes, somatostatin dynamics are altered. Increased somatostatin signaling suppresses glucagon secretion during hypoglycemia, impairing the counter-regulatory response. This contributes to hypoglycemia unawareness in long-standing diabetes. SSTR2 antagonists are being explored as potential treatments to restore hypoglycemia defense.

Somatostatin also has applications in gastrointestinal disorders. It reduces splanchnic blood flow and is used to treat variceal bleeding. It inhibits pancreatic secretion and has been tried for pancreatitis management.

Understanding somatostatin is important for anyone researching peptide stacking because multiple peptides may interact with somatostatin-regulated pathways.

Ghrelin: the hunger hormone from pancreatic epsilon cells

Most discussions of ghrelin focus on the stomach, where the majority is produced. But epsilon cells in the pancreatic islets also synthesize ghrelin, and their contribution, though small in adults, has important implications for islet function and development.

Discovery and structure

Ghrelin was discovered in 1999 as the endogenous ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. The 28-amino acid peptide is unique among known hormones because it requires a fatty acid modification for biological activity. An octanoyl group attaches to the third serine residue, a modification catalyzed by the enzyme GOAT.

This acylation is essential for binding to the ghrelin receptor (also called GHSR1a) and stimulating growth hormone release, appetite, and other effects. Des-acyl ghrelin, the form lacking the fatty acid, may have distinct biological activities through different receptors.

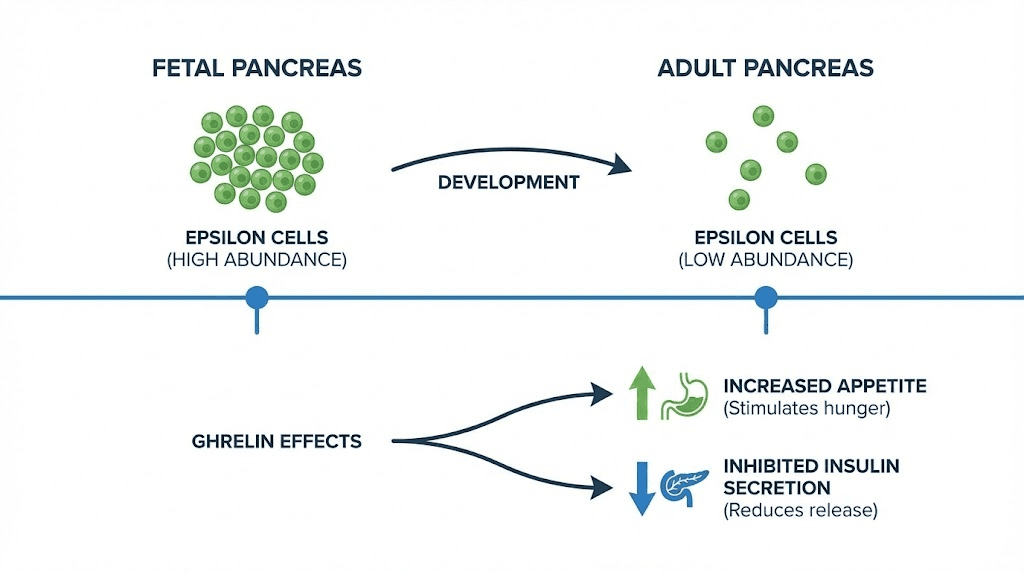

Pancreatic epsilon cells

Ghrelin-producing epsilon cells were identified in mouse pancreas in 2002. They represent the fifth endocrine cell type in the islets. In human fetal pancreas, epsilon cells are relatively abundant, comprising about 10% of islet cells during gestational weeks 15-26.

After birth, epsilon cell numbers decline dramatically. In adult humans, they account for less than 1% of islet cells. This developmental pattern contrasts with the stomach, where ghrelin cells are scarce during fetal development but expand significantly in adulthood.

The developmental abundance of pancreatic epsilon cells suggests important roles in islet formation. Research shows that ghrelin-expressing cells serve as multipotent progenitors that can differentiate into alpha cells, PP cells, and even beta cells.

Effects on islet function

Ghrelin inhibits insulin secretion from beta cells. The mechanism involves GHSR1a receptors, which couple to inhibitory signaling pathways. In isolated islets, ghrelin suppresses glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.

This inhibitory effect contributes to the pre-meal metabolic state. When you are hungry and ghrelin is elevated, insulin secretion is restrained. This makes physiological sense because promoting insulin release before food arrives would cause hypoglycemia.

However, ghrelin also has trophic effects on beta cells. It promotes beta cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis. These protective effects may be important for maintaining beta cell mass over time.

The relationship between ghrelin and energy metabolism extends beyond simple appetite stimulation. Ghrelin affects glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and body composition through multiple mechanisms.

Systemic effects of ghrelin

Most circulating ghrelin comes from the stomach, not the pancreas. Its primary effects include stimulating appetite, increasing growth hormone secretion, and promoting adipogenesis.

Ghrelin levels rise before meals and fall after eating. This pattern drives meal-related hunger. Ghrelin also increases gastric motility and acid secretion, preparing the stomach for incoming food.

The growth hormone-releasing effect occurs through direct action on pituitary somatotrophs. This pathway made ghrelin interesting for growth hormone optimization research, though the complexity of ghrelin signaling limits simple therapeutic applications.

Ghrelin influences reward pathways in the brain, increasing the hedonic value of food. This may explain why high-calorie foods seem more appealing when you are hungry. The same pathways may contribute to food addiction behaviors.

Clinical connections

Ghrelin levels are typically low in obesity, likely as a compensatory response to positive energy balance. However, ghrelin does not suppress normally after meals in obese individuals, potentially contributing to continued eating.

After gastric bypass surgery, ghrelin levels drop dramatically. Some researchers attribute part of the appetite suppression and weight loss following bariatric surgery to this ghrelin reduction.

Ghrelin agonists have been explored for conditions like cachexia and anorexia, where appetite stimulation is therapeutic. Ghrelin antagonists have been investigated for obesity treatment, though results have been mixed.

Amylin (IAPP): the co-secreted partner of insulin

Every time beta cells release insulin, they also release amylin. This 37-amino acid peptide, also called islet amyloid polypeptide, modulates nutrient handling in ways that complement insulin action. But amylin has a dark side too, contributing to beta cell death in type 2 diabetes.

Co-secretion with insulin

Amylin and insulin are stored together in beta cell secretory granules. They are released simultaneously in response to glucose and other secretagogues. The ratio is approximately 100:1, insulin to amylin.

This co-secretion means that factors affecting insulin release similarly affect amylin. In type 2 diabetes, as beta cell function declines, both insulin and amylin secretion become impaired.

Physiological functions

Amylin slows gastric emptying. Food moves from stomach to small intestine more gradually, spreading nutrient absorption over time. This prevents rapid glucose spikes after meals.

The peptide also promotes satiety, reducing food intake. It acts on brain regions involved in appetite control, including the area postrema. These effects complement insulin action by reducing the size and frequency of meals.

Amylin inhibits glucagon secretion from alpha cells, particularly in the postprandial period. This prevents inappropriate glucose release from the liver when blood sugar is already elevated from food absorption.

Together, these effects help coordinate the metabolic response to meals. Amylin fine-tunes the system in ways that insulin alone cannot achieve.

Receptor biology

Amylin signals through receptors formed by the calcitonin receptor complexed with receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs). Different RAMP combinations create receptors with different pharmacological properties.

These receptors are expressed in brain regions controlling food intake, gastric function, and glucose homeostasis. The area postrema, a circumventricular organ accessible to circulating peptides, is a key site of amylin action.

The amyloid connection

Human amylin is amyloidogenic, meaning it tends to aggregate into insoluble fibrils. These amyloid deposits are found in the pancreatic islets of most patients with type 2 diabetes and in elderly individuals without diabetes.

The aggregation process is toxic to beta cells. Intermediate oligomeric forms of amylin disrupt cell membranes, cause oxidative stress, and trigger apoptosis. This amyloid-induced beta cell death contributes to progressive decline in insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes.

Not all species develop islet amyloid. Rats and mice have amylin sequences with proline substitutions that prevent aggregation. These rodents do not develop islet amyloid even with severe diabetes. This species difference complicates using standard rodent models to study type 2 diabetes.

Research into preventing amylin aggregation or protecting beta cells from its toxicity is an active area. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to treatments that preserve beta cell mass in diabetes.

Therapeutic applications

Pramlintide is a synthetic amylin analog approved for diabetes treatment. It has substitutions that prevent aggregation while maintaining biological activity. Given as an injection before meals, it slows gastric emptying, reduces postprandial glucose excursions, and promotes modest weight loss.

Pramlintide is used alongside insulin in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. It replaces the amylin that beta cells no longer produce in adequate amounts.

Research continues into combination therapies using amylin analogs with other hormones. Dual agonists targeting both amylin and calcitonin receptors show promise for obesity treatment. The synergy between amylin signaling and other satiety pathways creates opportunities for combination approaches.

C-peptide: more than a byproduct

For decades, C-peptide was considered merely a byproduct of insulin synthesis, useful only as a marker of beta cell function. New research suggests it has biological activities of its own, challenging this dismissive view.

Origin and measurement

C-peptide is the 31-amino acid connecting segment removed from proinsulin during processing to mature insulin. It is released in equimolar amounts with insulin and circulates independently.

Clinically, C-peptide measurement offers advantages over insulin measurement. It has a longer half-life (30-35 minutes versus 3-5 minutes for insulin), providing a more stable signal. The liver does not extract C-peptide, unlike insulin, so peripheral levels better reflect total secretion. And C-peptide measurement can assess endogenous production even in patients receiving insulin injections.

Normal C-peptide levels range from 0.5 to 2.0 ng/mL fasting, rising 3-5 fold after meals. Low C-peptide indicates reduced beta cell function, as in type 1 diabetes or late type 2 diabetes. Elevated C-peptide suggests insulin resistance with compensatory hypersecretion or insulinoma.

Potential biological activities

Studies suggest C-peptide has anti-inflammatory effects, improves markers of endothelial function, and supports function of certain membrane transport proteins. In diabetic nephropathy, C-peptide administration has shown protective effects in some studies.

The mechanisms remain debated. C-peptide appears to bind to cell membranes, possibly interacting with G-protein coupled receptors, though a definitive receptor has not been identified. Signaling involves activation of Na+/K+-ATPase and endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

Clinical trials of C-peptide replacement in type 1 diabetes have shown mixed results. Some demonstrate improvements in nerve function and blood flow, particularly in early diabetic complications. Others have been less convincing.

The question of whether C-peptide is truly bioactive or whether observed effects reflect other factors remains actively investigated. The peptide research community continues to explore its potential.

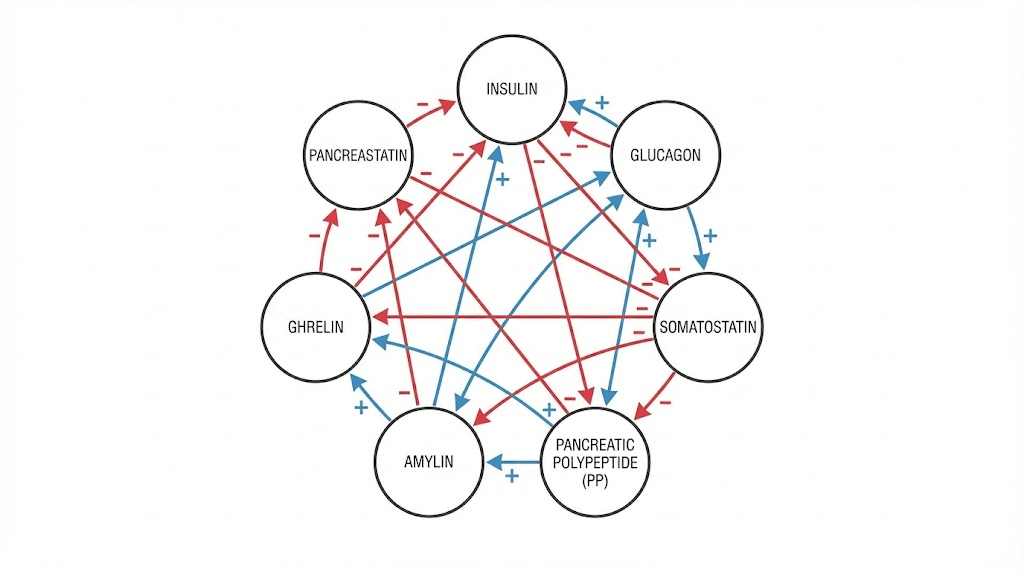

How pancreatic peptide hormones interact

These seven hormones do not work in isolation. They form an integrated network where changes in one affect all the others. Understanding these interactions is essential for interpreting metabolic physiology and developing therapeutic interventions.

The insulin-glucagon axis

Insulin and glucagon have opposing effects on blood glucose. When insulin rises, glucagon falls, and vice versa. This counter-regulation maintains glucose within narrow limits.

But the relationship goes beyond reciprocal changes. Insulin directly suppresses glucagon secretion through paracrine signaling within the islet. When beta cells die in type 1 diabetes, this local inhibition is lost. Alpha cells become hyperactive, producing excessive glucagon that worsens hyperglycemia.

Similarly, glucagon stimulates insulin secretion. This creates a feedback loop that helps coordinate responses to mixed meals containing both carbohydrates and protein.

Somatostatin as the master brake

Somatostatin inhibits both insulin and glucagon. Delta cells receive input from both beta and alpha cells, creating a three-way interaction.

When glucose rises, beta cells release insulin and signals like urocortin 3 that stimulate somatostatin release. Somatostatin then moderates further insulin secretion, preventing excessive release. It also suppresses glucagon, complementing insulin action.

During hypoglycemia, reduced insulin signaling decreases somatostatin release. This disinhibits alpha cells, allowing appropriate glucagon secretion to correct low glucose. When this system fails, as in longstanding diabetes, hypoglycemia becomes more dangerous.

Ghrelin modulation

Ghrelin inhibits insulin secretion, an effect that makes physiological sense. Before meals, when ghrelin is high, insulin should be low to maintain glucose for immediate use. After meals, ghrelin falls, releasing the inhibition on insulin secretion.

Ghrelin also opposes somatostatin release, creating complex dynamics. The interplay between these inhibitory and stimulatory signals fine-tunes islet output.

Amylin partnerships

Amylin co-release with insulin means their effects are coordinated temporally. After a meal, both hormones rise together. Insulin promotes glucose uptake while amylin slows gastric emptying and suppresses glucagon, creating a coordinated response that prevents glucose excursions.

The loss of amylin in diabetes contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia beyond what insulin deficiency alone would cause. This is why pramlintide replacement improves glycemic control even in patients already taking insulin.

Satiety signal integration

Pancreatic polypeptide and amylin both reduce food intake through central mechanisms. PP acts primarily on Y4 receptors while amylin works through calcitonin receptor complexes. These distinct pathways may have additive or synergistic effects.

After gastric bypass surgery, PP levels increase while ghrelin decreases. This shift in the satiety signal balance contributes to reduced appetite and sustained weight loss. Researchers exploring weight loss peptide stacks consider how to replicate these favorable hormonal patterns.

Pancreatic peptide hormones in disease states

Dysfunction of pancreatic hormones underlies or contributes to numerous conditions. Understanding these pathological states illuminates normal physiology and guides therapeutic development.

Type 1 diabetes

Autoimmune destruction of beta cells eliminates insulin and amylin production. But the consequences extend further. Without local insulin signaling, glucagon secretion becomes dysregulated. Alpha cells produce excessive glucagon, contributing to hyperglycemia and ketosis.

The loss of paracrine insulin signaling also affects delta cells. Somatostatin dynamics change, further impairing the counter-regulatory response to hypoglycemia. This explains why hypoglycemia is such a dangerous complication in type 1 diabetes.

C-peptide levels in type 1 diabetes are very low or undetectable, confirming the absence of endogenous insulin production. Preserving residual C-peptide, a goal of several intervention trials, associates with better glycemic control and fewer complications.

Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes involves both insulin resistance and progressive beta cell failure. Early in the disease, beta cells compensate by producing more insulin. Hyperinsulinemia results. But over time, beta cells exhaust and insulin production declines.

Amylin secretion parallels insulin. Early hyperamylinemia may contribute to islet amyloid deposition, which then kills beta cells in a vicious cycle. This amyloid-mediated toxicity is a major mechanism of beta cell loss in type 2 diabetes.

Glucagon secretion is inappropriately elevated in type 2 diabetes. Despite high blood glucose, alpha cells continue producing glucagon. This paradoxical secretion worsens fasting hyperglycemia. The mechanisms include impaired paracrine inhibition from defective beta cells and possibly direct alpha cell abnormalities.

GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide address multiple defects. They enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion from remaining beta cells, suppress glucagon, slow gastric emptying, and promote satiety, mimicking effects of both insulin and amylin.

Obesity

Pancreatic hormone alterations in obesity create a permissive environment for continued weight gain. Insulin resistance requires compensatory hyperinsulinemia, which promotes fat storage and suppresses lipolysis.

Postprandial PP responses are often blunted in obesity. Reduced satiety signaling may contribute to overconsumption. Amylin responses may also be impaired.

Ghrelin levels are typically low in obesity, probably as compensation. However, ghrelin does not suppress normally after meals, potentially driving continued eating.

Therapeutic strategies targeting these pathways include GLP-1 agonists, amylin analogs, and potentially PP-based approaches. The success of tirzepatide demonstrates the power of multi-receptor targeting.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

Tumors can arise from any pancreatic endocrine cell type. Insulinomas cause hypoglycemia. Glucagonomas cause hyperglycemia and a distinctive rash. VIPomas cause watery diarrhea. PPomas often produce few symptoms but can cause mass effects.

These tumors illustrate what happens when hormone production escapes normal control. Treatment typically involves surgical removal, with somatostatin analogs used to control hormone excess when surgery is not possible.

Chronic pancreatitis

Progressive pancreatic destruction in chronic pancreatitis eliminates both exocrine and endocrine function. The resulting diabetes, called pancreatogenic diabetes, differs from type 2 diabetes in important ways.

All islet hormones are reduced. Insulin deficiency causes hyperglycemia. But glucagon and PP deficiency creates additional problems. Without glucagon, counter-regulation is impaired, making hypoglycemia common and dangerous. Without PP, hepatic insulin sensitivity decreases.

PP replacement has been studied in pancreatogenic diabetes with promising results on glucose metabolism. This represents a potential therapeutic approach distinct from standard diabetes treatment.

Research frontiers in pancreatic peptide hormones

Active research continues to expand our understanding of pancreatic hormones and develop new therapeutic applications.

Multi-agonist therapeutics

Single molecules that activate multiple hormone receptors are showing remarkable efficacy. Tirzepatide targets both GLP-1 and GIP receptors. Retatrutide adds glucagon receptor activity. These multi-agonists produce greater weight loss and metabolic improvement than single-receptor drugs.

Future combinations might incorporate amylin receptor activity, Y4 receptor effects, or other pathways. The challenge is achieving the right balance of activities without adverse effects.

Beta cell regeneration

Replacing lost beta cells could cure type 1 diabetes. Research explores stimulating proliferation of remaining beta cells, converting alpha or other cells into beta cells, and deriving new beta cells from stem cells.

Several pancreatic hormones influence beta cell mass. GLP-1 and GIP promote proliferation and survival. Ghrelin has trophic effects. Understanding how these signals coordinate may reveal ways to stimulate regeneration.

Islet amyloid prevention

Preventing amylin aggregation could preserve beta cell function in type 2 diabetes. Approaches include small molecules that stabilize amylin monomers, compounds that promote amyloid clearance, and therapies that protect cells from amyloid toxicity.

The peptide research field is actively investigating these possibilities. Success could transform diabetes treatment by addressing a root cause of beta cell death.

PP-based obesity treatment

Long-acting PP analogs and Y4 receptor agonists are in development. The satiety-inducing effects of PP, combined with its effects on hepatic insulin sensitivity, make it an attractive target.

Challenges include the short half-life and aggregation tendency of native PP. Novel formulations using lipid-based delivery systems or stabilized analogs may overcome these limitations.

Glucagon modulation in diabetes

Suppressing inappropriate glucagon secretion could improve glycemic control. Glucagon receptor antagonists have been tested but face challenges including hepatic side effects.

More targeted approaches might work better. Enhancing somatostatin signaling specifically to alpha cells, or restoring proper paracrine communication within islets, could suppress glucagon without systemic effects.

Epsilon cell manipulation

The progenitor-like properties of ghrelin-expressing epsilon cells open possibilities for regenerative medicine. If these cells can be expanded and directed to differentiate into functional beta cells, they could provide a source for cell replacement therapy.

Understanding what determines epsilon cell fate and how to control differentiation remains an active research area.

Practical implications for peptide researchers

SeekPeptides provides this information because understanding pancreatic hormones is fundamental to peptide research. Here are key takeaways for researchers.

Metabolic context matters

Any peptide affecting metabolism will interact with pancreatic hormone systems. Growth hormone releasing peptides influence glucose homeostasis. Weight loss peptides affect appetite signaling that pancreatic hormones help regulate. Even healing peptides may have metabolic effects worth monitoring.

When designing protocols, consider how your interventions might affect or be affected by insulin, glucagon, and other pancreatic hormones.

Timing considerations

Pancreatic hormones follow distinct temporal patterns. Insulin and amylin spike after meals. Glucagon and ghrelin rise during fasting. PP remains elevated for hours after eating. These rhythms affect the metabolic environment in which other peptides operate.

Administering a peptide in fed versus fasted state may produce different results. Consider whether meals affect your research variables and standardize accordingly.

Individual variation

Pancreatic hormone responses vary between individuals due to genetics, metabolic health, age, and other factors. People with insulin resistance have different baseline conditions than insulin-sensitive individuals. Diabetics have altered hormone profiles entirely.

This variability affects reproducibility. Standardizing metabolic status in research protocols improves consistency.

Safety monitoring

Many peptides can affect blood glucose. Safety considerations include monitoring for hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, or changes in glucose tolerance. Understanding which pancreatic hormones might be affected helps predict and monitor for adverse effects.

Interactions with diabetes medications are particularly important. Peptides that enhance insulin secretion or sensitivity could potentiate hypoglycemia in people taking insulin or sulfonylureas.

Synergy opportunities

The success of multi-receptor agonists like tirzepatide demonstrates the power of targeting complementary pathways. Understanding pancreatic hormone interactions can guide rational combination approaches in peptide research.

For weight loss, combining satiety-enhancing peptides with those improving insulin sensitivity might produce better results than either alone. For metabolic health, addressing multiple hormonal defects simultaneously makes physiological sense.

SeekPeptides members access detailed protocols and guidance for optimizing their research while understanding these fundamental metabolic considerations.

Frequently asked questions

What are the main hormones produced by the pancreas?

The pancreatic islets produce seven peptide hormones: insulin from beta cells, glucagon from alpha cells, somatostatin from delta cells, pancreatic polypeptide from PP cells, ghrelin from epsilon cells, and both amylin and C-peptide from beta cells alongside insulin. Each has distinct metabolic functions, from glucose regulation to appetite control.

How do insulin and glucagon work together?

Insulin lowers blood glucose by promoting uptake and storage. Glucagon raises blood glucose by stimulating liver glucose release. They form a counter-regulatory pair that maintains blood glucose within narrow limits. When one rises, the other typically falls, creating reciprocal control of metabolism.

What is pancreatic polypeptide used for?

Pancreatic polypeptide is a satiety hormone that reduces appetite and food intake. It also slows gastric emptying and regulates digestive secretions. Research suggests it may improve hepatic insulin sensitivity. PP-based therapies are being explored for obesity and diabetes treatment.

Why does amylin matter in diabetes?

Amylin works with insulin to control blood glucose after meals. It slows gastric emptying, reduces glucagon, and promotes satiety. In diabetes, amylin production declines along with insulin. Pramlintide, a synthetic amylin, is used to improve glycemic control beyond what insulin alone achieves.

Can pancreatic hormone imbalances cause weight gain?

Yes. Insulin resistance drives compensatory hyperinsulinemia, which promotes fat storage. Reduced PP and amylin responses impair satiety signaling. Altered ghrelin dynamics may contribute to overconsumption. Weight management strategies increasingly target these hormonal pathways.

What is C-peptide and why is it measured?

C-peptide is a byproduct of insulin production, released in equal amounts with insulin. Unlike insulin, it is not extracted by the liver and has a longer half-life. C-peptide measurement assesses endogenous insulin production, distinguishes diabetes types, and monitors beta cell function in research and clinical settings.

How does somatostatin affect other pancreatic hormones?

Somatostatin inhibits both insulin and glucagon secretion. Delta cells act as a brake on both hormones, preventing excessive swings. This creates a local regulatory mechanism that coordinates islet responses to nutrients and other signals.

Are there peptide therapies targeting pancreatic hormones?

Yes, several. GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide enhance insulin secretion. Pramlintide replaces amylin. Tirzepatide targets both GLP-1 and GIP receptors. Research continues on PP analogs, glucagon modulators, and multi-receptor agonists for metabolic diseases.

External resources

For researchers serious about understanding metabolic peptides, SeekPeptides offers comprehensive protocols, evidence-based guides, and a community of experienced researchers who have navigated these exact questions.