Feb 3, 2026

A peptide that kills fat cells. Not by suppressing appetite. Not by speeding up metabolism. By cutting off their blood supply entirely.

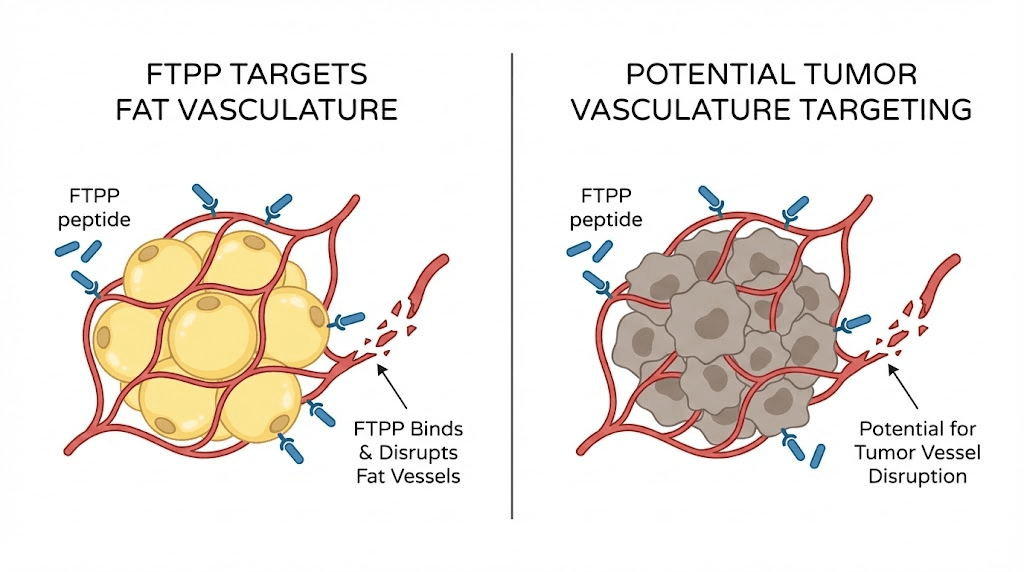

That is what FTPP peptide does, at least in animal models. Known formally as adipotide and scientifically as prohibitin-targeting peptide 1, this experimental compound represents one of the most radical approaches to fat loss research ever developed. While compounds like traditional weight loss peptides work through hormonal pathways or metabolic adjustments, FTPP takes a completely different route. It finds the blood vessels feeding white fat tissue, triggers programmed cell death in those vessels, and starves the fat cells until they die.

The results in primate studies were remarkable. Obese rhesus monkeys lost 11% of their body weight in 28 days. Their fat deposits shrank by 39%. Insulin resistance improved dramatically, sometimes within days of starting treatment. These numbers surpassed what most fat burning peptides achieve in animal research, and they caught the attention of researchers worldwide.

But there is a catch. There is always a catch with compounds this aggressive. Kidney stress emerged as the primary side effect in every study. A Phase 1 clinical trial was started in 2012 and then quietly discontinued. The peptide remains experimental, unapproved, and controversial. This guide covers everything the research has revealed about FTPP, from its molecular mechanism and preclinical results to its safety profile, how it compares to other weight management peptides, and what the future holds for this unusual compound. SeekPeptides members rely on evidence-based research like this to understand even the most experimental compounds in the peptide landscape.

What is FTPP peptide

FTPP stands for Fat-Targeted Proapoptotic Peptide. The name tells you exactly what it does. It targets fat. It triggers apoptosis, which is the scientific term for programmed cell death. And it does both with a specificity that surprised even its creators.

The peptide is more commonly known by its trade name, adipotide, and its scientific designation, prohibitin-targeting peptide 1 (prohibitin-TP01). It was developed at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center by researchers led by Mikhail Kolonin and Wadih Arap. Their original work, published in Nature Medicine in 2004, was not actually about fat loss at all. They were studying vascular targeting as a cancer treatment strategy.

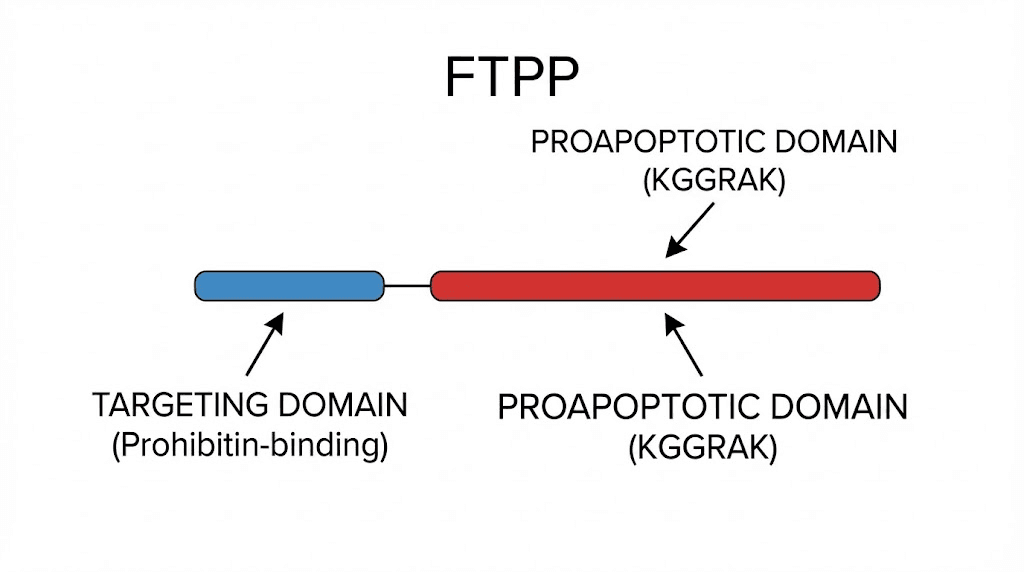

The breakthrough came when they discovered that a specific peptide sequence, CKGGRAKDC, could selectively bind to blood vessels supplying white adipose tissue. This was unexpected. Blood vessels are blood vessels, or so researchers assumed. But this peptide could tell the difference between vessels feeding fat and vessels feeding everything else in the body.

They combined this targeting sequence with a proapoptotic domain, D(KLAKLAK)2, that disrupts mitochondrial membranes when internalized by cells. The result was a two-part molecule. The first part finds fat tissue vasculature. The second part destroys it.

The full sequence reads CKGGRAKDC-GG-D(KLAKLAK)2. That hyphenated mess of letters represents something genuinely novel in peptide science. Unlike most peptides used in weight management research, FTPP does not interact with hormone receptors. It does not mimic natural signaling molecules. It is a synthetic weapon designed for one purpose: destroying the infrastructure that keeps fat cells alive.

How FTPP works at the molecular level

Understanding FTPP requires understanding prohibitin. Not the concept of prohibition, but a specific protein called prohibitin-1 (PHB1).

Prohibitin is a membrane protein found in nearly every cell in your body. Inside cells, it helps stabilize mitochondria, regulate the cell cycle, and control apoptosis. It is one of those multitasking proteins that evolution has repurposed for dozens of different jobs depending on where it sits in the cell.

But here is the critical detail. While intracellular prohibitin expression is everywhere, cell surface prohibitin localization is selective. It appears on the outside of cells in only a few places. One of those places is the endothelial cells lining blood vessels that supply white adipose tissue. This makes surface prohibitin a vascular marker, a flag that essentially says "this blood vessel feeds fat."

FTPP exploits this flag.

The targeting sequence binds to a receptor complex formed by two proteins: prohibitin-1 and annexin A2 (ANXA2). These two proteins interact on the surface of vascular endothelial cells specifically in white adipose tissue. Research published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight confirmed that this PHB-ANXA2 complex exists in both mouse and human white fat vasculature, which was a critical finding for translational relevance.

Once FTPP binds to this receptor complex, the proapoptotic domain gets internalized into the endothelial cell. The D(KLAKLAK)2 sequence is an amphipathic peptide that disrupts mitochondrial membranes. When it reaches the mitochondria inside the endothelial cell, it triggers a cascade that leads to mitochondrial collapse and cell death.

The vascular collapse cascade

Here is what happens step by step when FTPP reaches fat tissue:

Step 1: Receptor binding. The CKGGRAKDC targeting sequence finds and binds to the PHB1-ANXA2 receptor complex on endothelial cells of white fat vasculature. This binding is highly specific. The receptors form a unique complex in fat tissue vasculature that does not appear to exist in the same configuration elsewhere in the body.

Step 2: Internalization. The entire FTPP molecule gets pulled inside the endothelial cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis. This is the same process cells use to absorb nutrients and signaling molecules from their environment.

Step 3: Mitochondrial disruption. Once inside, the D(KLAKLAK)2 domain targets the mitochondrial membrane. It inserts into the membrane, disrupts its integrity, and triggers the release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors. This is the point of no return.

Step 4: Endothelial cell death. The affected endothelial cells undergo apoptosis. They die in an orderly, programmed fashion rather than through necrosis, which would cause inflammation.

Step 5: Vascular atrophy. As endothelial cells die, the blood vessels feeding the fat tissue shrink and collapse. The microvasculature that supplies oxygen and nutrients to white adipocytes is progressively destroyed.

Step 6: Fat cell ischemia. Deprived of blood supply, the fat cells experience ischemic injury. Without oxygen and nutrients, they cannot maintain their metabolic functions. The adipocytes begin to die.

Step 7: Clearance. The dead fat cells and vascular debris are cleared by the immune system through normal phagocytic processes. The body reabsorbs the remnants.

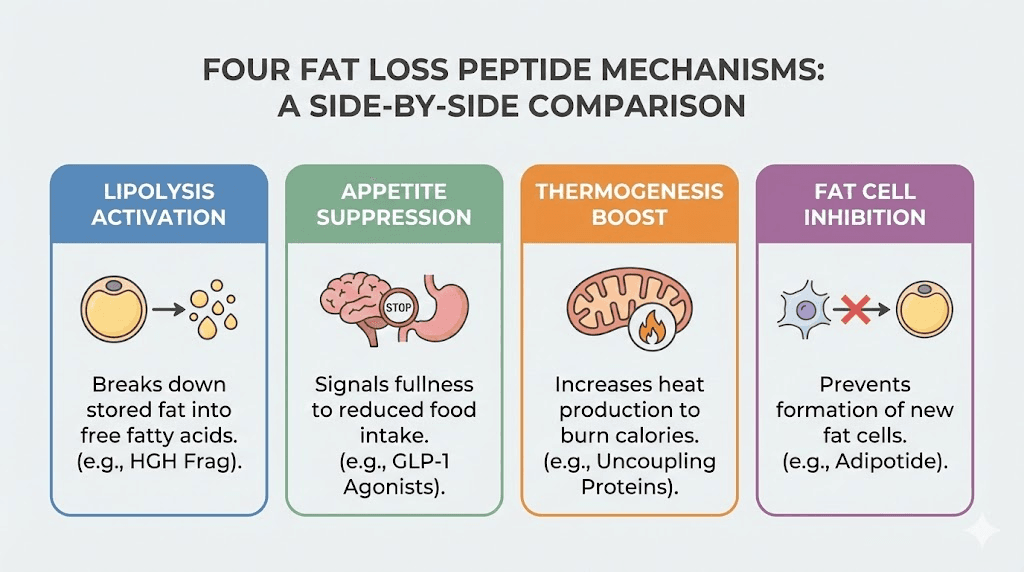

This entire process is fundamentally different from how other lipotropic peptides work. Compounds like AOD 9604 stimulate lipolysis, breaking down fat stored inside existing cells. Cagrilintide and retatrutide work through appetite suppression and metabolic signaling. FTPP does not tell fat cells to release their contents or tell the brain to eat less. It kills the infrastructure. The fat cells die because they have no blood supply left.

Why it targets only white fat

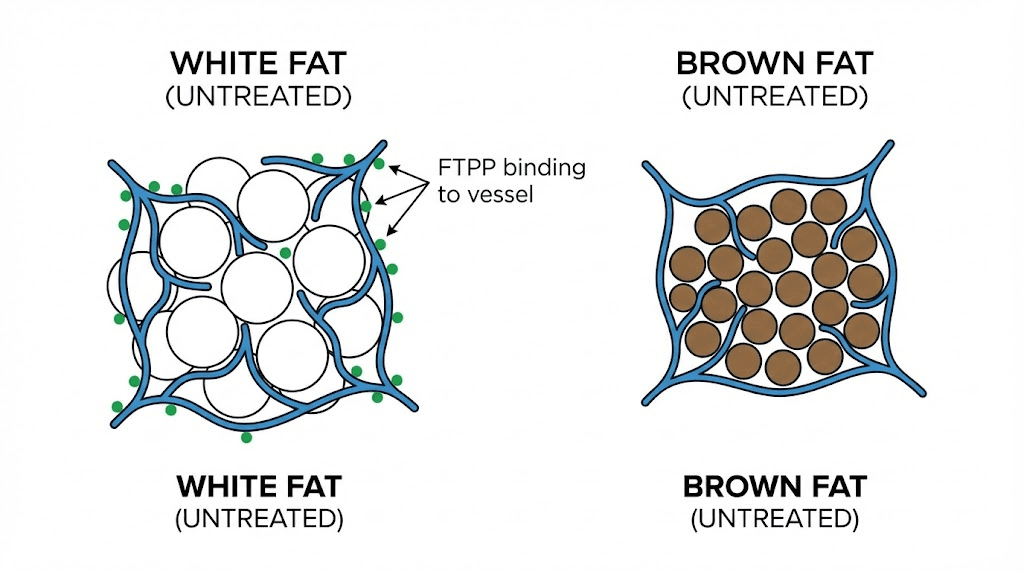

One of the most interesting aspects of FTPP is its selectivity. The peptide targets white adipose tissue while apparently sparing brown adipose tissue entirely.

White fat stores energy. It is the fat you want to lose. Brown fat burns energy for heat through a process called thermogenesis, and it is metabolically beneficial. The PHB1-ANXA2 receptor complex that FTPP targets appears on the vasculature of white fat but not brown fat. This means FTPP can reduce harmful white fat deposits without disrupting the beneficial thermogenic activity of brown fat.

Research also confirmed that the PHB1-ANXA2 complex plays a role in fatty acid transport. In white fat vasculature, these proteins work together with CD36, a fatty acid transporter, to shuttle long-chain fatty acids from the bloodstream into adipocytes. Disrupting this complex does not just kill blood vessels. It may also interfere with the normal uptake of fatty acids into fat cells even before the vasculature collapses completely.

Studies on mice lacking annexin A2 showed normal fat tissue vascularization and adipogenesis but reduced fatty acid uptake, resulting in smaller fat deposits. This suggests the PHB-ANXA2 system has multiple roles in fat biology, and FTPP may be affecting more pathways than just the obvious vascular destruction.

The Kolonin mouse study that started everything

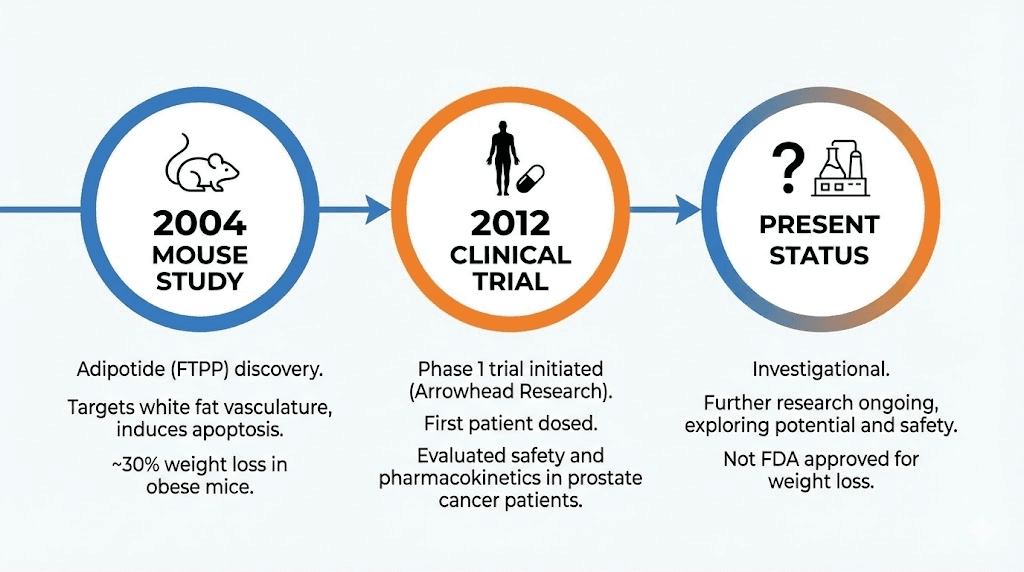

In 2004, Mikhail Kolonin and colleagues published a landmark study in Nature Medicine titled "Reversal of obesity by targeted ablation of adipose tissue." This was the paper that introduced the world to vascular-targeted fat destruction.

The researchers used a technique called in vivo phage display to identify peptide sequences that would home specifically to white adipose tissue vasculature. Out of billions of random peptide sequences, one kept showing up in the blood vessels of fat tissue: CKGGRAKDC. They then identified its binding partner as prohibitin, establishing PHB as a vascular marker of white fat.

They conjugated this targeting sequence to the proapoptotic D(KLAKLAK)2 motif and tested the resulting compound in obese mice.

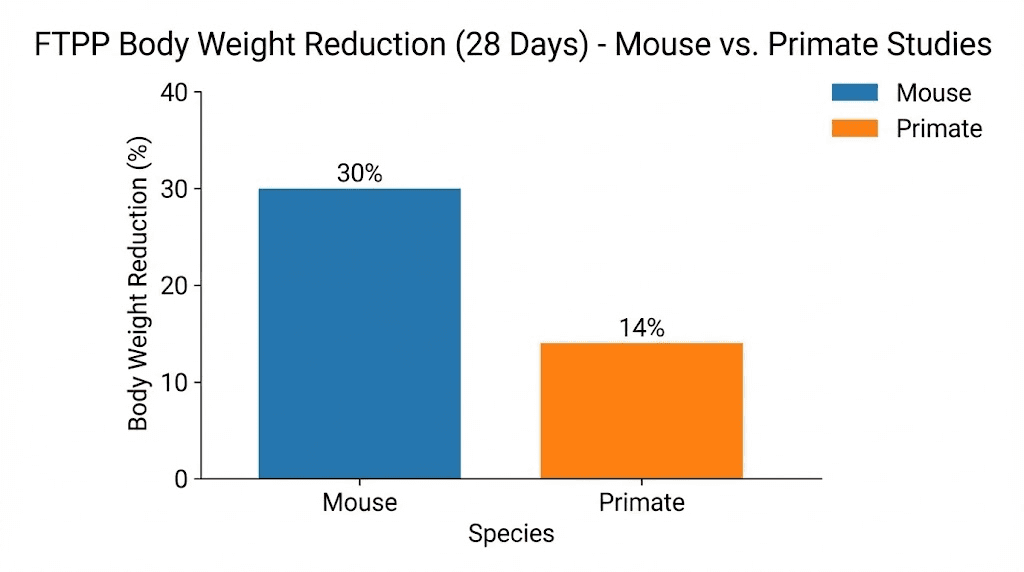

The results were dramatic. Obese mice treated with the compound for 28 days showed approximately a 30% reduction in body weight. The fat loss was visually obvious and confirmed by tissue analysis. White fat depots were significantly reduced, while brown fat remained intact.

Importantly, the weight loss occurred only in obese mice on high-fat diets. Lean mice on regular diets did not lose significant weight. This suggested that the peptide preferentially targets the expanded vasculature associated with obesity, not normal fat tissue maintenance.

The study also reported that the mice showed improved metabolic parameters, including better glucose tolerance and lower insulin levels. These metabolic improvements appeared to start before significant weight loss was visible, suggesting that disrupting white fat vasculature has metabolic effects beyond simple fat reduction.

No significant adverse effects were reported in the mouse study. The selectivity appeared to hold. Fat vasculature died. Everything else seemed fine. But mice are not humans, and the research community knew that the real test would come in larger, more complex animals.

The primate studies that changed the conversation

The mouse results were impressive but preliminary. Rodent metabolism is different enough from human metabolism that many promising mouse treatments fail in primates. The FTPP research team knew they needed primate data, and they got it.

The pivotal primate study was published in Science Translational Medicine in 2011. It used three species of Old World monkeys: rhesus macaques, baboons, and cynomolgus macaques. The primary subjects were spontaneously obese rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), considered one of the most relevant primate models for human obesity.

Results in obese rhesus monkeys

Ten obese female rhesus monkeys received daily adipotide injections for 28 days, followed by 28 days of no treatment (a washout period). The results confirmed and exceeded the mouse findings.

Average body weight reduction was 11%. That number might sound modest compared to the 30% seen in mice, but context matters. An 11% reduction in body weight over 28 days in a primate is substantial. For comparison, semaglutide, the most successful FDA-approved weight loss drug, produces 10-15% body weight reduction over many months in humans.

Fat deposits decreased by 39% on average. This is where the real story lies. MRI and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans confirmed marked reductions in white adipose tissue throughout the body. Both subcutaneous and visceral fat decreased significantly.

Body mass index decreased. Abdominal circumference decreased. These are exactly the kinds of changes that correlate with reduced cardiovascular risk and improved metabolic health in humans.

Metabolic improvements

The metabolic changes were arguably more interesting than the weight loss itself.

Insulin resistance improved dramatically. Treated monkeys used approximately 50% less insulin after treatment while maintaining normal blood glucose levels. This is the hallmark of improved insulin sensitivity, and it has enormous implications for metabolic health.

Glucose tolerance improved rapidly. Researchers noted metabolic improvements as early as day 3 of treatment, before any noticeable weight loss had occurred. This rapid, weight-independent improvement in glucose tolerance suggests that disrupting white fat vasculature directly affects metabolic signaling, possibly by interfering with adipokine production or fatty acid metabolism.

Serum triglycerides decreased. The insulinogenic index, a measure of how much insulin the body needs to maintain glucose control, dropped significantly. Free fatty acid levels showed a modest but meaningful reduction.

These findings suggest FTPP does more than just remove fat. By targeting the vasculature that supports white adipose tissue, it appears to interrupt some of the metabolic dysfunction associated with obesity at a fundamental level. The improvement in glucose handling within days, before significant fat loss, indicates that white fat vasculature itself may play an active role in metabolic regulation beyond just supplying fat cells with nutrients.

What happened to the fat

A valid concern with destroying fat tissue is where the released lipids go. If you kill millions of fat cells, their stored triglycerides have to end up somewhere. Could they accumulate in the liver, causing fatty liver disease? Could they clog arteries?

The researchers addressed this directly. They examined more than 40 tissues from the treated monkeys, looking for ectopic fat accumulation. They checked the liver, the arterial walls, and the circulation. They found no evidence of increased lipid storage in any non-adipose tissue.

The released lipids appeared to be processed normally through metabolic pathways. The gradual nature of the fat cell death, occurring over days rather than minutes, likely allowed the body to handle the lipid load through normal metabolic processing rather than overwhelming any single organ.

The kidney problem

Every discussion of FTPP eventually arrives here. The kidneys.

In every primate study, kidney effects emerged as the primary side effect. The researchers described these effects as "relatively mild, predictable, and reversible renal injury and altered tubular function." That description is accurate but perhaps understates the significance of what they observed.

What the studies showed

Monkeys necropsied 24 hours after the final dose of adipotide showed kidney lesions that were dose-dependent. At the lowest dose, lesions were scored as minimal to mild. At the middle dose, most animals showed minimal to mild lesions. At the highest dose, lesions ranged from minimal to moderate.

The primary lesions were classified as degenerative and necrotic, specifically single-cell necrosis in kidney tubules. There were also reactive and regenerative changes, indicating the kidney was trying to repair itself.

Serum creatinine levels increased during treatment. Creatinine is filtered by the kidneys, and elevated levels typically indicate reduced kidney function. However, there was an unusual pattern: creatinine rose without a corresponding increase in blood urea nitrogen (BUN). This dissociation between creatinine and BUN is not typical of straightforward kidney damage.

Why the kidneys are affected

The kidney issue is not random. There is a specific biochemical explanation.

The D(KLAKLAK)2 proapoptotic domain of FTPP uses D-amino acids (the mirror image of the natural L-amino acids used in most biological proteins). When FTPP is cleared from the body, it passes through the kidneys. Renal D-amino acid oxidase, an enzyme found in kidney tubules, is the only known mammalian enzyme that can use the D(KLAKLAK)2 moiety as a substrate.

This means the kidneys are not just filtering FTPP. They are actively metabolizing it. The breakdown process appears to generate toxic intermediates or local concentrations of the proapoptotic domain that damage tubular cells. The kidney is essentially poisoning itself by trying to break down the peptide.

Some researchers have also proposed that cleared FTPP might compete with creatinine for transport systems in the proximal tubule, which would explain the creatinine elevation without true glomerular damage.

Reversibility

The good news, and this is important, is that the kidney effects appeared reversible. Monkeys necropsied after a recovery period showed only minimal residual tubular changes. The lesions healed. Kidney function returned toward normal.

The researchers adjusted dosages in subsequent experiments and found they could modulate the kidney impact. None of the test monkeys suffered permanent kidney damage when dosages were managed appropriately.

However, "reversible" is relative. In a controlled laboratory setting with veterinary monitoring, blood work, and dose adjustments, kidney problems can be caught and managed. Outside of a research environment, the situation could be very different. Without monitoring, what starts as reversible tubular injury could progress to something more serious.

The Bostin Loyd case

In bodybuilding communities, FTPP gained notoriety partly because of bodybuilder Bostin Loyd, who reportedly developed stage 5 kidney failure. While the direct causation between his FTPP use and kidney failure has been debated, the case became a cautionary tale that circulated widely in peptide forums and bodybuilding communities. It underscores the gap between controlled research settings and real-world use, where monitoring protocols, safety standards, and dose management may be inadequate or absent entirely.

The Phase 1 clinical trial

Based on the promising primate data, a Phase 1 clinical trial was initiated. On July 11, 2012, Arrowhead Research Corporation announced that the first patient had been dosed with Adipotide in a human clinical trial.

The trial design was unusual. Rather than testing adipotide in obese patients directly, they chose patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer who had no standard treatment options remaining. This choice was strategic for several reasons.

First, prohibitin has been implicated in various cancers, including prostate cancer. The same vascular targeting mechanism that destroys fat blood vessels could potentially disrupt tumor vasculature. Second, terminal cancer patients represent a population where the risk-benefit calculation is different. Side effects that would be unacceptable for weight loss might be tolerable in patients with no other options.

The protocol called for patients to receive daily subcutaneous injections for 28 days. Up to five dose levels would be tested, with three participants at each level. They would start at the lowest dose and escalate based on safety observations.

Then it stopped.

The trial was discontinued for reasons that were never publicly specified. No safety data from the human trial was published. No efficacy results were shared. The clinical development of adipotide was effectively abandoned as of 2019.

What happened? Speculation ranges from unacceptable kidney toxicity in humans to business decisions by Arrowhead Research (which pivoted to RNA interference therapeutics) to challenges with the regulatory pathway. Without published data, we simply do not know whether FTPP worked in humans, whether the side effects were manageable, or whether any positive signals emerged.

This information gap is one of the most frustrating aspects of FTPP research. A compound with genuinely novel mechanism data from multiple animal species, demonstrated efficacy, and a clear molecular target essentially disappeared from the clinical pipeline without public explanation.

FTPP compared to other fat loss peptides

To understand where FTPP fits in the broader landscape of fat loss peptides, it helps to compare mechanisms, efficacy, and safety profiles. Each compound approaches the problem of excess body fat from a completely different angle.

FTPP vs AOD 9604

AOD 9604 is a modified fragment of human growth hormone (amino acids 177-191) that stimulates lipolysis (fat breakdown) and inhibits lipogenesis (fat creation). It works through metabolic pathways, encouraging fat cells to release their stored triglycerides for use as energy.

The difference is fundamental. AOD 9604 tells fat cells to empty themselves. FTPP kills the blood vessels feeding them. AOD 9604 leaves fat cells intact but slimmer. FTPP removes them permanently. AOD 9604 has minimal reported side effects. FTPP causes kidney stress.

For researchers interested in metabolic modulation without aggressive tissue destruction, AOD 9604 represents a gentler approach. For those studying targeted tissue ablation, FTPP offers a more dramatic mechanism.

FTPP vs semaglutide and tirzepatide

GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide and dual agonists like tirzepatide and retatrutide represent the current gold standard in pharmaceutical weight loss. They work by mimicking gut hormones that signal satiety, reduce appetite, slow gastric emptying, and improve insulin signaling.

These compounds are FDA-approved (semaglutide and tirzepatide), extensively studied in large human trials, and produce 10-24% body weight reductions depending on the specific drug. Their side effects, primarily gastrointestinal issues like nausea and constipation, are well-characterized and generally manageable.

FTPP operates on a completely different principle. It does not affect appetite or hormonal signaling. It physically destroys fat tissue infrastructure. The mechanisms are not competing, they are complementary in theory. But FTPP has no human efficacy data, no FDA approval, and significantly more concerning side effects.

FTPP vs CJC-1295 and ipamorelin

Growth hormone secretagogues like CJC-1295 and ipamorelin enhance the body natural growth hormone production. This hormonal boost supports fat metabolism, lean muscle growth, and recovery. The fat loss is indirect, working through improved metabolic efficiency over time.

Where FTPP attacks existing fat deposits by destroying their blood supply, CJC-1295 and ipamorelin help the body burn fat more efficiently through natural hormonal pathways. The timelines are different too. FTPP shows dramatic effects in 28 days. Growth hormone secretagogues typically require months of consistent use.

FTPP vs 5-amino-1MQ

5-amino-1MQ inhibits the NNMT enzyme, which plays a role in fat cell metabolism and energy expenditure. It is a small molecule rather than a peptide, but it shows up in discussions about precision fat loss compounds because of its targeted approach to metabolic regulation.

While 5-amino-1MQ modulates fat cell metabolism to reduce fat accumulation, FTPP bypasses metabolism entirely and goes straight to vascular destruction.

They represent opposite ends of the aggression spectrum in fat reduction research.

Comparison table

Feature | FTPP (Adipotide) | AOD 9604 | Semaglutide | CJC-1295/Ipamorelin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Mechanism | Destroys fat vasculature | Stimulates lipolysis | GLP-1 appetite suppression | Growth hormone release |

FDA approved | No | No | Yes | No |

Human trial data | Discontinued/unpublished | Limited | Extensive | Limited |

Fat cell fate | Permanent destruction | Intact but emptied | Intact but shrunk | Intact but metabolized |

Primary side effects | Kidney stress | Minimal | GI issues | Water retention, numbness |

Speed of results | Days to weeks | Weeks to months | Weeks to months | Months |

Reversibility of fat loss | Permanent (cells die) | Reversible | Reversible if stopped | Reversible if stopped |

The permanent nature of FTPP fat loss is worth emphasizing. When fat cells die through vascular starvation, they do not regenerate quickly. Most other fat loss approaches shrink existing fat cells, which can refill if the intervention stops. FTPP removes them. This is both its greatest advantage and a source of concern, because removing too much fat tissue could have consequences for metabolic homeostasis, hormone production, and energy storage capacity.

The prohibitin connection: why this protein matters beyond FTPP

Prohibitin is a fascinating protein that has implications far beyond fat loss. Understanding it helps explain both why FTPP works and why its mechanism has attracted interest from cancer researchers, metabolic scientists, and aging researchers.

Prohibitin in mitochondrial function

Inside mitochondria, prohibitin complexes (formed by PHB1 and PHB2 subunits) act as molecular chaperones that help maintain mitochondrial structure and function. They stabilize newly synthesized mitochondrial proteins, regulate mitochondrial morphology, and influence how mitochondria fuse and divide.

This mitochondrial role is what makes the D(KLAKLAK)2 proapoptotic domain effective. When it reaches the mitochondria inside a target cell, it disrupts the very structures that prohibitin normally protects. The irony is elegant: FTPP uses prohibitin as a homing beacon to find fat vasculature, then destroys the mitochondria that prohibitin normally maintains.

Prohibitin in cancer

Prohibitin has been implicated in breast, prostate, and ovarian cancers. Its expression levels change in cancerous cells, and it appears to play roles in tumor cell proliferation and survival. This is why the Phase 1 clinical trial chose prostate cancer patients. The researchers hypothesized that the vascular targeting mechanism used against fat could also work against tumors.

Tumor vasculature shares some similarities with adipose vasculature. Both involve rapidly growing blood vessel networks that support tissue expansion. If FTPP can target and destroy one, the same principle might apply to the other. This concept, called ligand-directed vascular targeting, remains an active area of peptide research.

Prohibitin and fatty acid transport

Recent research has revealed that the PHB-ANXA2 complex does more than just sit on cell surfaces waiting to be targeted by synthetic peptides. It actively participates in fatty acid transport into adipose tissue.

The complex interacts with CD36, a fatty acid transporter, to facilitate the movement of long-chain fatty acids from the bloodstream through endothelial cells and into adipocytes. Studies on mice lacking ANXA2 showed that this transport system is important for normal fat tissue development. Without it, mice had normal blood vessel formation in fat tissue but reduced fatty acid uptake, resulting in smaller fat depots.

This finding has implications beyond FTPP. It suggests that the prohibitin-annexin A2 system could be a pharmaceutical target for gentler anti-obesity approaches. Rather than destroying blood vessels entirely, you could potentially interfere with this fatty acid transport system to reduce fat accumulation without the dramatic tissue destruction and kidney side effects of FTPP.

Nanoparticle delivery systems

Building on the FTPP concept, researchers have explored using nanoparticles to deliver proapoptotic cargo specifically to fat vasculature. Cytochrome C-loaded prohibitin-targeted nanoparticles (PTNPs) have shown the ability to induce apoptosis in white fat blood vessel endothelial cells and prevent diet-induced obesity in mice in a dose-dependent manner.

These nanoparticle approaches may eventually address the kidney problem. By packaging the therapeutic cargo differently, it may be possible to maintain the fat-targeting selectivity while reducing the renal toxicity that plagued the original FTPP molecule. This is still early-stage research, but it represents a logical evolution of the FTPP concept.

Dosing protocols from preclinical research

Since FTPP has no approved human dosing and the Phase 1 trial data was never published, all dosing information comes from animal studies. These numbers provide context for researchers but should not be interpreted as recommendations for any purpose.

Mouse studies

In the original Kolonin mouse study, obese mice received daily injections of the adipotide peptidomimetic for 28 days. The specific doses in the published research focused on demonstrating proof of concept rather than establishing detailed dose-response curves. The 30% body weight reduction in 28 days was achieved at doses optimized for the mouse model.

Importantly, lean mice on regular diets did not show significant weight loss at the same doses. This suggests a threshold effect related to the degree of fat tissue vascularization. More fat means more target vasculature, which means more binding sites for FTPP.

Primate GLP study

The Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) compliant primate study tested three dose levels in lean rhesus monkeys: 0.25, 0.43, and 0.75 mg/kg administered daily for 28 days. Fifteen monkeys were divided into cohorts of three at each dose level.

At the lowest dose (0.25 mg/kg), lean monkeys did not show significant weight loss but showed minimal kidney effects. At the highest dose (0.75 mg/kg), kidney lesions were more pronounced but still classified as minimal to moderate. The dose-dependent relationship was clear: more FTPP meant more fat loss but also more kidney stress.

In the efficacy study with obese monkeys, the dosing regimen that produced the 11% body weight loss and 39% fat deposit reduction over 28 days was not precisely detailed in all publications, but researchers described managing doses to balance efficacy against renal function.

Duration considerations

All published FTPP studies used 28-day treatment cycles. This was followed by a washout period where the compound was discontinued. The 28-day protocol appears to be sufficient for significant fat reduction while limiting cumulative kidney exposure.

No published data exists on longer treatment durations, repeated cycles, or chronic dosing. The kidney toxicity mechanism, specifically the breakdown of D-amino acids by renal enzymes, would likely make extended continuous use problematic.

Route of administration

FTPP was administered via subcutaneous injection in the clinical trial protocol and in most preclinical studies. The subcutaneous route allows for gradual absorption and distribution, which may help moderate peak concentrations and reduce acute toxicity compared to intravenous administration.

For researchers interested in peptide injection techniques, the standard subcutaneous injection protocols used for other injectable peptides would apply. Proper reconstitution and storage are critical for maintaining peptide integrity.

Safety profile and risk assessment

FTPP carries more safety concerns than most peptides in the research space. Any honest assessment needs to address these directly.

Confirmed risks from preclinical data

Renal toxicity. This is the headline concern. Every primate study showed dose-dependent kidney effects. The mechanism is understood (renal D-amino acid oxidase metabolizes the proapoptotic domain), but understanding the mechanism does not eliminate the risk. Researchers noted elevated serum creatinine, tubular degeneration, single-cell necrosis, and altered tubular function.

Dehydration. Some studies noted mild dehydration in treated animals. This is potentially significant because dehydration compounds kidney stress. A peptide that already causes renal strain combined with dehydration could accelerate kidney damage.

Dose sensitivity. The therapeutic window appears narrow. The dose that produces significant fat loss is close to the dose that causes concerning kidney lesions. This narrow margin leaves little room for error.

Theoretical concerns

Ectopic fat deposition. When fat tissue is destroyed, the stored lipids must go somewhere. While the primate studies found no evidence of ectopic fat accumulation in the liver or arterial walls, the concern remains valid for larger-scale or longer-duration use. Some experts have raised the possibility that destroying too much white fat could redirect lipids to the liver, increasing the risk of hepatic steatosis.

Loss of metabolic reserve. White adipose tissue is not just a passive storage depot. It produces hormones (adipokines) that regulate metabolism, appetite, inflammation, and immune function. Destroying significant amounts of fat tissue could disrupt these hormonal signals in ways that are difficult to predict.

Brown fat sparing uncertainty. While studies suggest FTPP spares brown fat, the degree of certainty varies. Brown adipose tissue is metabolically precious, responsible for thermogenesis and energy expenditure. Any off-target effects on brown fat would be harmful.

Long-term consequences unknown. The longest published follow-up after FTPP treatment is the washout period in the primate studies. No data exists on what happens months or years after treatment. Do new fat cells eventually grow back? Does the destroyed vasculature regenerate? Are there delayed effects?

Monitoring recommendations from research

Based on the preclinical data, any research involving FTPP would require careful monitoring of:

Kidney function. Regular serum creatinine and BUN measurements. Urinalysis for proteinuria or other markers of tubular damage. Any elevation should trigger dose adjustment or discontinuation.

Hydration status. Maintaining adequate hydration is critical to reduce additional kidney stress. Proper fluid protocols should be established before beginning any research.

Metabolic parameters. Blood glucose, insulin, lipid panels, and liver function tests would help track both efficacy and potential adverse metabolic effects.

Body composition. Rather than just tracking weight, DEXA scans or similar body composition measurements would distinguish between fat loss, muscle loss, and water loss.

FTPP and cancer research

The original concept behind FTPP, targeting specific vasculature for destruction, was borrowed from cancer research. And the traffic goes both ways. Insights from FTPP have fed back into oncology research.

Tumors need blood vessels to grow. This concept, called tumor angiogenesis, has driven an entire class of cancer drugs (anti-angiogenics like bevacizumab). But most anti-angiogenic drugs work broadly, affecting blood vessels throughout the body. FTPP demonstrated that it is possible to target specific vascular beds with molecular precision.

The Phase 1 trial choice of prostate cancer patients was not random. Prohibitin is overexpressed in several cancer types. Prostate cancer vasculature may express surface prohibitin in configurations similar to adipose vasculature, making it potentially vulnerable to the same targeting approach.

Beyond direct therapeutic applications, FTPP has become a valuable research tool. Scientists use it to study the role of adipose tissue vasculature in metabolic disease, to investigate the PHB-ANXA2 receptor system, and to develop next-generation vascular targeting strategies. Even if FTPP itself never becomes a drug, the principles it demonstrated have opened new avenues in both obesity and cancer research.

Reconstitution and handling

For researchers working with FTPP in laboratory settings, proper handling follows the same general principles as other research peptides but with some specific considerations.

FTPP typically comes as a lyophilized (freeze-dried) powder. Like all lyophilized peptides, it should be stored at -20 C or lower before reconstitution. The storage conditions matter because the proapoptotic domain can degrade if exposed to moisture or temperature fluctuations.

Reconstitution follows standard protocols using bacteriostatic water or sterile water. The peptide reconstitution calculator on SeekPeptides can help determine proper dilution ratios. Gentle swirling rather than vigorous shaking is important to avoid damaging the peptide structure.

Once reconstituted, FTPP should be refrigerated at 2-8 C and used within a reasonable timeframe. Like most reconstituted peptides, shelf life after reconstitution is limited. Researchers should prepare only the amount needed for near-term use.

FTPP vials are typically supplied in 10mg quantities. The peptide calculator and mixing guides can help with determining reconstitution volumes for specific concentration targets. Maintaining sterile technique during reconstitution is essential, as with any injectable preparation.

The regulatory landscape

FTPP exists in a complex regulatory gray area that researchers and enthusiasts should understand.

The peptide has no FDA approval for any indication. The Phase 1 clinical trial was discontinued without published results. It is not a controlled substance, but it is also not approved as a therapeutic, dietary supplement, or anything else that would allow legal human use.

FTPP is sold by research chemical suppliers as a "research peptide" or "for research use only." This designation means it can be legally purchased for legitimate research purposes but is not intended for human consumption. The legal status of peptides varies by jurisdiction, and researchers should understand their local regulations.

The regulatory environment for peptides continues to evolve. Some peptides that were formerly available as research chemicals have been reclassified or restricted. FTPP current availability as a research chemical does not guarantee its future status.

For researchers conducting legitimate in vitro or animal studies, FTPP can typically be obtained through established peptide suppliers with appropriate documentation. Third-party testing and verification of purity and identity is always advisable, as the research peptide market has quality variability.

Common questions about FTPP from research communities

Based on discussions across peptide forums and research communities, several questions come up repeatedly about FTPP. Here are answers based on the published research.

Can FTPP be combined with other fat loss peptides

No published research exists on combining FTPP with other peptide stacks. In theory, FTPP mechanism (vascular destruction) is complementary to metabolic approaches like AOD 9604 (lipolysis stimulation) or appetite suppressants. However, stacking an aggressive compound with known kidney toxicity with additional peptides that also need to be cleared by the kidneys would logically increase renal burden. No data supports the safety of any combination.

Does FTPP affect muscle tissue

The published research suggests FTPP is selective for white adipose tissue vasculature and does not directly target muscle tissue or its blood supply. The PHB1-ANXA2 receptor complex targeted by FTPP appears specific to fat vasculature. However, indirect effects on muscle are possible if significant metabolic disruption occurs during rapid fat loss.

How quickly does FTPP work

In primate studies, metabolic improvements appeared as early as day 3. Measurable weight loss became apparent within the first week. The full 28-day treatment cycle produced the headline results (11% body weight, 39% fat reduction). The speed is faster than most other peptide timelines, which typically require weeks to months for visible effects.

Is the fat loss from FTPP permanent

In principle, yes. Fat cells destroyed through vascular starvation do not regenerate quickly. Adult humans have a relatively fixed number of fat cells (adipocyte turnover is slow, roughly 10% per year). However, complete long-term data on fat regrowth after FTPP treatment does not exist. It is possible that the body eventually regenerates new fat tissue and vasculature, especially if the metabolic conditions that drove original fat accumulation persist.

Why was the clinical trial stopped

The official reasons were never disclosed. Possible explanations include unacceptable toxicity in human subjects, business strategy changes at Arrowhead Research Corporation (which shifted focus to RNA therapeutics), regulatory challenges, or a combination of factors. Without published data from the trial, this remains one of the most significant unanswered questions about FTPP.

Can FTPP cause fat to accumulate in the liver

The primate studies specifically checked for this and found no evidence of ectopic fat deposition in the liver, arterial walls, or any of more than 40 examined tissues. However, this was over a 28-day treatment period followed by a limited observation window. Longer-term studies would be needed to fully assess this risk.

Frequently asked questions

What does FTPP stand for?

FTPP stands for Fat-Targeted Proapoptotic Peptide. The name describes its function: it targets fat tissue and triggers apoptosis (programmed cell death) in the blood vessels supplying that tissue. It is also known by its trade name adipotide and its scientific name prohibitin-targeting peptide 1.

Is FTPP the same as adipotide?

Yes. FTPP, adipotide, and prohibitin-TP01 all refer to the same compound. FTPP describes its function (fat-targeted proapoptotic peptide), adipotide is the trade name used in clinical contexts, and prohibitin-TP01 references its molecular target. The peptide sequence is CKGGRAKDC-GG-D(KLAKLAK)2 regardless of which name is used.

Has FTPP been tested in humans?

A Phase 1 clinical trial was initiated in 2012 by Arrowhead Research Corporation. The first patient was dosed in July 2012. The trial enrolled prostate cancer patients. However, the trial was discontinued and no human data was ever published. The reasons for discontinuation were not disclosed publicly.

How does FTPP differ from other weight loss peptides?

Most weight loss peptides work through hormonal or metabolic pathways, suppressing appetite or increasing fat metabolism. FTPP takes a completely different approach by destroying the blood vessels that supply white fat tissue with oxygen and nutrients. This causes fat cells to die from lack of blood supply rather than from metabolic changes.

What are the main side effects of FTPP?

The primary side effect observed in all animal studies is kidney stress. This includes elevated serum creatinine, tubular degeneration, and single-cell necrosis in kidney tissue. Effects were dose-dependent and appeared reversible upon discontinuation in controlled research settings. Mild dehydration was also noted. The compound has not been studied enough in humans to characterize its full side effect profile.

Can FTPP target specific areas of fat?

FTPP does not target specific body regions. It binds to the PHB1-ANXA2 receptor complex found on blood vessels supplying white adipose tissue throughout the body. Both subcutaneous fat and visceral fat were reduced in primate studies. The selectivity is between white fat and other tissues, not between different fat deposits.

Is FTPP legal to purchase?

FTPP can be legally purchased in many jurisdictions as a research chemical for legitimate laboratory use. It is not approved by the FDA or any other regulatory agency for human therapeutic use. Peptide legality varies by country and can change, so researchers should verify current regulations in their jurisdiction.

Does FTPP affect brown fat?

Published research indicates FTPP is selective for white adipose tissue and does not appear to affect brown adipose tissue. The PHB1-ANXA2 receptor complex that FTPP targets is found on white fat vasculature but not brown fat vasculature. This selectivity means thermogenic brown fat, which is beneficial for energy expenditure and metabolic health, should remain unaffected.

The future of vascular-targeted fat reduction

FTPP may never become a drug. The kidney toxicity, the discontinued clinical trial, and the rise of highly effective GLP-1 agonists have all reduced its commercial viability. But the science behind FTPP is far from dead.

The concept of targeting specific vasculature for therapeutic purposes has spawned an entire research field. Nanoparticle delivery systems that use prohibitin targeting to deliver proapoptotic cargo to fat vasculature are in development. These systems could potentially maintain the selectivity of FTPP while reducing off-target effects, including kidney toxicity, by altering how the drug is packaged and released.

The discovery that the PHB-ANXA2 complex regulates fatty acid transport has opened another avenue. Rather than destroying blood vessels, researchers could potentially develop drugs that interfere with fatty acid uptake into fat tissue, reducing fat accumulation without the dramatic tissue destruction. This approach would be gentler, potentially safer, and could be used chronically rather than in short treatment cycles.

Gene therapy approaches that modify prohibitin expression in fat vasculature are also being explored, though these are in very early stages. The idea of selectively modifying gene expression in specific vascular beds to control fat tissue growth represents a longer-term vision.

For now, FTPP remains primarily a research tool. Scientists use it to study white adipose tissue biology, vascular biology, and metabolic regulation. Every experiment with FTPP teaches something about how fat tissue is organized, maintained, and supported by its blood supply. These insights feed into broader obesity research and may eventually contribute to treatments that are more practical than FTPP itself.

SeekPeptides provides members with up-to-date research analyses on experimental compounds like FTPP, helping researchers understand both the potential and limitations of cutting-edge peptide science. For those tracking the rapidly evolving weight loss peptide landscape, understanding compounds like FTPP provides important context for evaluating newer, more refined approaches.

For researchers serious about staying informed on the full spectrum of peptide research, from FDA-approved therapies to experimental compounds like FTPP, SeekPeptides offers the most comprehensive resource available. Members access evidence-based guides, detailed protocol information, and a community of thousands who navigate these complex research questions together.

External resources

Nature Medicine: Reversal of obesity by targeted ablation of adipose tissue (Kolonin et al. 2004)

JCI Insight: Prohibitin/annexin 2 interaction regulates fatty acid transport in adipose tissue

PMC: Prohibitin/annexin 2 interaction in white adipose tissue

In case I do not see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night. May your research stay rigorous, your peptides stay pure, and your protocols stay evidence-based. Join us here.