Jan 26, 2026

Your collagen powder lists 11 grams of protein per scoop. You add it to your morning coffee religiously. But at the end of the day, when you tally your macros, should those 11 grams count toward your protein target? The answer is more complicated than the nutrition label suggests.

Here is the problem. Collagen peptides receive a protein quality score of zero. Literally zero. By official nutritional standards, collagen cannot legally contribute to the percent daily value of protein on food labels. Yet collagen is undeniably a protein, made of amino acids, digested and absorbed like other proteins.

This contradiction confuses millions of people trying to optimize their nutrition. Some experts say collagen absolutely counts toward daily protein. Others insist it should never be counted. Both camps cite legitimate research to support their positions.

The truth lies somewhere in the middle, and understanding where requires examining how protein quality is measured, what makes collagen biochemically unique, and what the latest research reveals about incorporating collagen into a protein-focused diet. SeekPeptides members access comprehensive peptide resources that go deeper into these mechanisms, but this guide provides everything you need to make informed decisions about collagen and your protein requirements.

Understanding protein quality and why it matters

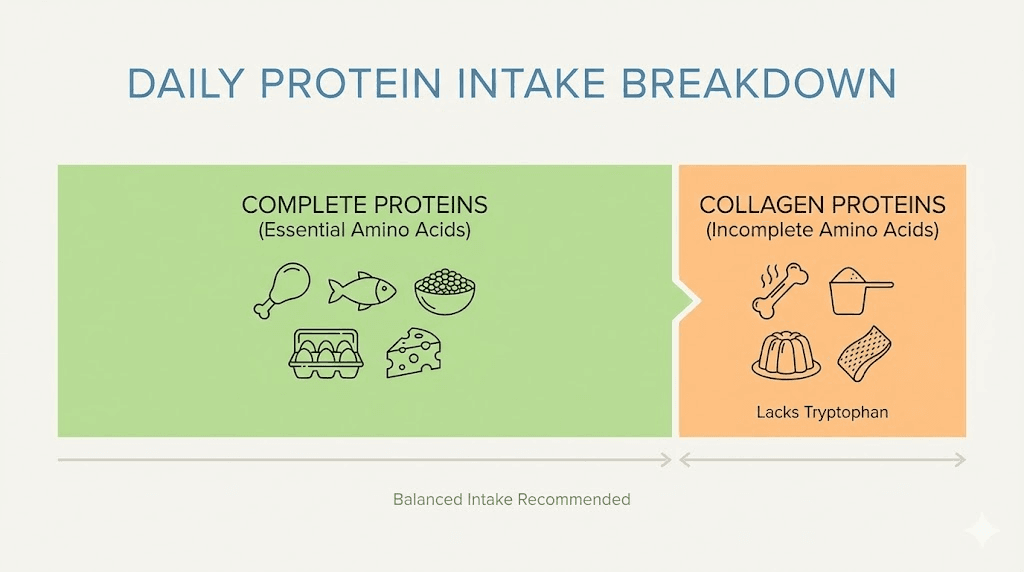

Not all proteins are equal. This statement sounds controversial, but it reflects basic biochemistry. Your body needs specific building blocks, amino acids, to function properly. Nine of these are essential, meaning your body cannot manufacture them. You must get them from food.

Complete proteins contain all nine essential amino acids in adequate amounts.

Incomplete proteins lack one or more essential amino acids or contain them in insufficient quantities. This distinction matters because your body cannot store amino acids for later. It needs a full complement of essential amino acids available simultaneously to build and repair tissue effectively.

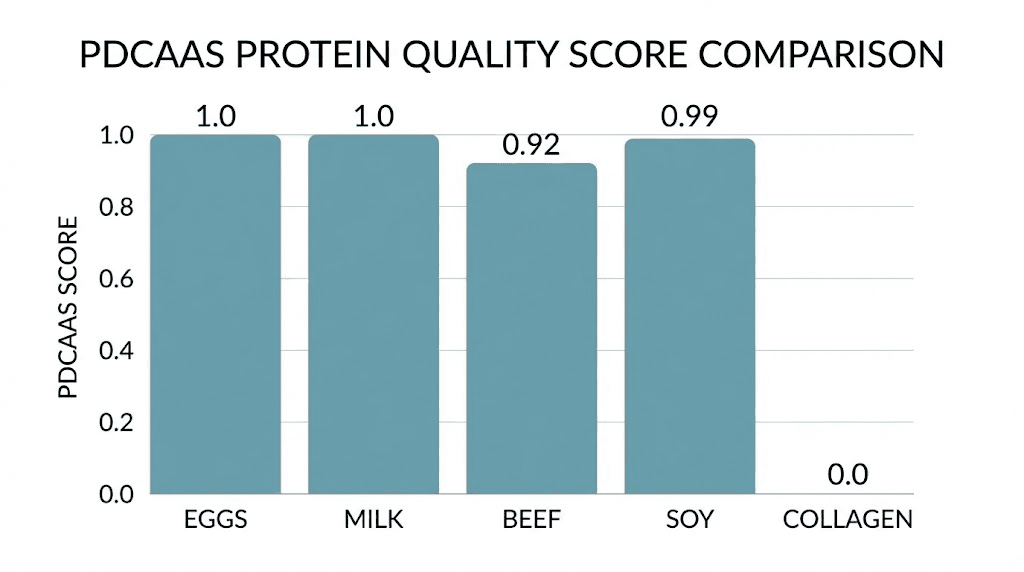

The protein quality debate centers on a measurement system called PDCAAS, the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score. This system, adopted by the FDA and WHO, evaluates proteins based on two factors: their amino acid profile compared to human requirements, and how efficiently the body can digest and absorb them.

How PDCAAS scoring works

PDCAAS assigns scores from 0 to 1.0, with 1.0 representing perfect protein quality. The calculation involves comparing a protein source amino acid profile against a reference pattern representing human needs, then adjusting for digestibility.

Here is where things get interesting for collagen.

The system identifies whichever essential amino acid falls furthest below the reference pattern. This becomes the limiting amino acid. The score reflects this lowest point, not an average of all amino acids. A protein could be excellent in eight essential amino acids but score poorly if one is missing or severely limited.

Eggs score 1.0. Milk scores 1.0. Beef scores around 0.92. Soy protein hits 0.91. These foods provide balanced essential amino acid profiles with good digestibility. They can fully support your protein needs when consumed in sufficient quantities.

Collagen scores 0.0.

Yes, zero. Not 0.5. Not 0.3. Zero.

Why collagen scores zero

Collagen lacks tryptophan entirely. This essential amino acid is completely absent from collagen structure. Under PDCAAS rules, having zero of any essential amino acid automatically produces a score of zero, regardless of how abundant other amino acids might be.

Mathematically, anything multiplied by zero equals zero. Collagen could contain perfect amounts of the other eight essential amino acids, and its score would still be zero because of missing tryptophan.

This creates a regulatory consequence. Foods cannot claim protein content contribution to daily value when their PDCAAS score is zero. That is why collagen supplements show protein grams on the nutrition facts but cannot list a percent daily value for protein.

But does this zero score mean collagen is nutritionally worthless as a protein source? The research suggests otherwise.

The amino acid profile of collagen peptides

Understanding why collagen scores zero requires examining its unique amino acid composition. Collagen is not just missing tryptophan. Its entire amino acid profile differs dramatically from complete proteins like meat, eggs, or dairy.

About 47% of collagen consists of just three amino acids: glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline. This concentration is extraordinary. No other dietary protein comes close to this distribution. Glycine alone accounts for roughly one-third of collagen total amino acid content.

Compare this to milk protein. Milk contains about 11% glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline combined. Essential amino acids make up approximately 43% of milk protein. For collagen, essential amino acids represent only about 14% of total content.

These numbers explain why collagen fails as a sole protein source. The body needs essential amino acids for critical functions including muscle protein synthesis, enzyme production, and neurotransmitter creation. Collagen simply does not provide adequate amounts.

What collagen does provide

The amino acids abundant in collagen serve different purposes than essential amino acids from complete proteins. Glycine supports sleep quality, detoxification pathways, and connective tissue formation. Proline is critical for joint health and skin elasticity. Hydroxyproline is essentially exclusive to collagen-containing tissues.

These amino acids are classified as conditionally essential or non-essential because healthy bodies can synthesize them. However, synthesis capacity may not always meet demands, especially during aging, injury, or high physical stress.

Modern diets often lack glycine. Our ancestors consumed whole animals, including connective tissues, bones, and skin rich in collagen. Today, most people eat primarily muscle meat, which contains minimal glycine. This shift may create relative deficiencies even though glycine is technically non-essential.

Supplementing with collagen peptides restores these amino acids to the diet. Whether this counts as meeting protein needs depends on how you define protein needs.

The glycine gap in modern diets

Research from researchers studying amino acid metabolism suggests that endogenous glycine synthesis falls about 10 grams per day short of total body requirements for someone eating a standard Western diet. The body compensates, but this compensation may come at metabolic costs.

Supplementing 10-15 grams of collagen daily, typical for most collagen supplements, provides roughly 3-5 grams of glycine. This does not fully close the gap but makes a meaningful contribution.

From this perspective, collagen provides nutritional value that PDCAAS scoring completely ignores. The system was designed to evaluate proteins for supporting growth and maintenance of lean body mass. It was not designed to assess specialized amino acid contributions that support connective tissue, sleep, or other functions.

The 36% rule: collagen in a balanced diet

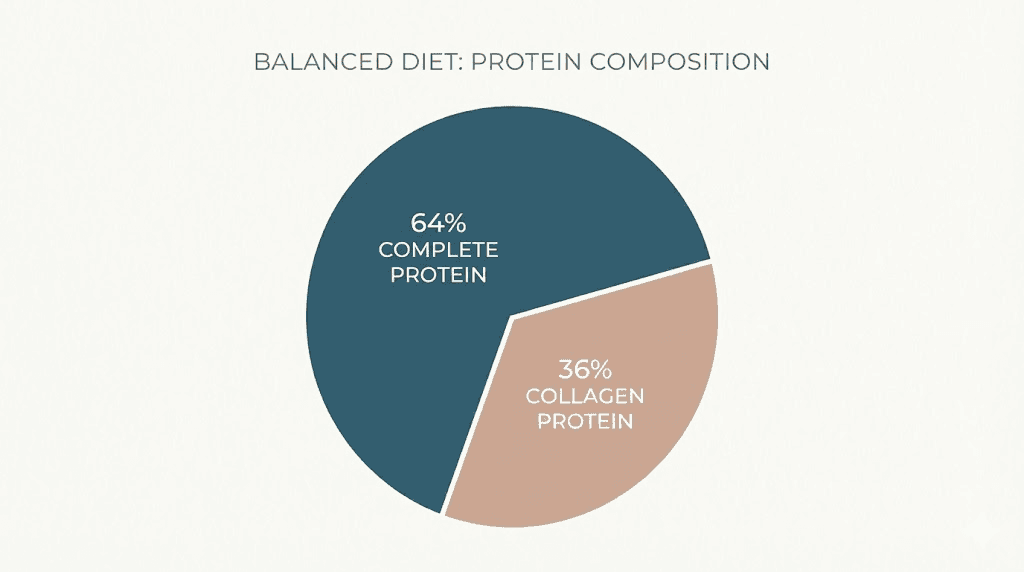

A landmark study published in the journal Nutrients examined how much collagen could replace other proteins in a typical diet while still meeting essential amino acid requirements. The researchers performed iterative PDCAAS calculations to find the upper limit.

Their finding: up to 36% of total daily protein can come from collagen peptides without compromising essential amino acid status.

This number deserves unpacking.

Consider someone eating 100 grams of protein daily from various sources including meat, dairy, eggs, and plant foods. The study suggests 36 grams could theoretically come from collagen while the remaining 64 grams from complete proteins would provide sufficient tryptophan and other essential amino acids to maintain overall diet quality.

The math works because complete proteins contain excess essential amino acids beyond minimum requirements. Meat provides far more tryptophan than the body strictly needs. This surplus creates room for incorporating collagen without dropping below essential amino acid thresholds.

What this means practically

Typical collagen supplement doses range from 2.5 to 15 grams daily. Even at the higher end, this represents a small fraction of most people total protein intake. Someone eating 100 grams of protein who adds 15 grams from collagen has collagen representing only 15% of their protein, well under the 36% ceiling.

For most supplementation scenarios, the 36% rule is never approached. This means standard collagen supplementation alongside a varied diet poses no risk of essential amino acid deficiency.

The study effectively validated what many nutritionists suspected: collagen can safely contribute to total protein intake when other protein sources are present. It cannot stand alone as a protein source, but it need not be excluded from protein calculations entirely.

Limitations of the 36% research

The study modeled the standard American diet. People eating extremely restrictive diets, those with very high protein requirements, or those with specific amino acid needs might have different thresholds.

Athletes requiring 1.6-2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight for muscle building have higher essential amino acid demands. Their 36% ceiling might be lower in practice because they need more total essential amino acids.

Vegetarians and vegans already manage limited dietary sources of certain amino acids. Adding collagen to an already restricted amino acid intake could be more problematic than adding it to an omnivore diet.

The research provides a useful framework but should be applied with awareness of individual circumstances.

Collagen versus whey protein for muscle building

If the question is whether collagen counts as protein for meeting basic nutritional requirements, the answer is yes, within limits. But if the question is whether collagen builds muscle as effectively as complete proteins, the answer is definitively no.

Research published in the International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism compared whey protein to leucine-matched collagen peptides during a 10-week resistance training program. Despite matching leucine content, the amino acid most associated with muscle protein synthesis, whey protein produced significantly greater gains in muscle thickness.

Another study in healthy older women found that whey protein stimulated muscle protein synthesis in both resting and exercising conditions. Collagen peptides only stimulated synthesis during exercise, and the magnitude was lower than whey in both conditions.

The mechanism is straightforward.

Muscle protein synthesis requires all essential amino acids to proceed optimally. Collagen low essential amino acid content, particularly its complete lack of tryptophan and low leucine levels, limits its ability to drive muscle building. The body cannot make muscle from glycine and proline alone.

When collagen complements muscle building

Collagen may support muscle building indirectly through its effects on joints and connective tissue. Stronger tendons and ligaments allow for heavier training loads. Better recovery from joint stress enables more frequent training.

One study found that combining 25 grams of whey protein with 5 grams of collagen peptides enhanced both muscle and connective tissue protein synthesis better than either protein alone. The combination approach captures whey muscle-building benefits while gaining collagen support for joints.

For athletes, this suggests a practical strategy. Use complete proteins like whey, casein, or whole foods to meet muscle protein synthesis requirements. Add collagen separately to support connective tissue health. Count the collagen toward total protein intake but do not rely on it for muscle building.

The leucine threshold

Muscle protein synthesis responds most strongly when dietary protein provides at least 2-3 grams of leucine per meal. This threshold triggers the mTOR pathway that initiates muscle building.

Whey protein is about 11% leucine by weight. A 25-gram serving provides nearly 3 grams of leucine, hitting the threshold easily.

Collagen contains roughly 3% leucine. A 25-gram serving provides only about 0.75 grams of leucine, well below the threshold. You would need roughly 80 grams of collagen to match the leucine in 25 grams of whey, an impractical amount that would provide excessive glycine and minimal other essential amino acids.

The biochemistry is clear. For muscle building, collagen cannot substitute for complete proteins. But for overall protein intake and specialized connective tissue benefits, collagen has its place.

How much collagen is safe to consume daily

Research supports daily collagen intake of 2.5 to 15 grams as safe and potentially beneficial. This range appears across multiple clinical trials studying various outcomes from skin health to joint function.

Safety studies have found no significant adverse effects at these doses when used for periods up to six months. Some studies have extended to 12 months without safety concerns. Collagen peptides are generally well tolerated with minimal reported side effects.

Higher doses have been used in some research contexts. Athletes in some studies consumed 15-20 grams daily. While these doses appear safe for healthy individuals, they are not necessarily more effective than lower doses for most outcomes.

Dosing by health goal

The optimal dose depends on what you are trying to achieve.

For skin health, doses as low as 2.5 grams daily have shown benefits in clinical trials. Studies finding improvements in skin elasticity, hydration, and wrinkle depth typically used 2.5-10 grams daily. Higher doses have not consistently shown additional skin benefits.

For joint health, most positive research used 10 grams daily. Studies on osteoarthritis pain and exercise-related joint discomfort often used this dose. Some research suggests specific collagen types like type II undenatured collagen may work at lower doses around 40 milligrams, but this is a different form than hydrolyzed collagen peptides.

For connective tissue support in athletes, 15 grams daily combined with vitamin C is a common protocol. Research on tendon and ligament adaptation to exercise used this dose with promising results.

For general supplementation, 10 grams daily represents a reasonable middle ground capturing most potential benefits without excessive intake.

Timing considerations

Research on connective tissue synthesis suggests taking collagen 30-60 minutes before exercise may optimize delivery to tendons and ligaments. The amino acids become available as blood flow to connective tissue increases during activity.

For skin and general health benefits, timing appears less critical. Consistent daily intake matters more than specific timing. Some people prefer taking collagen in the morning with coffee, others at night. Neither approach has clear advantages based on current research.

Pairing collagen with vitamin C may enhance its effectiveness. Vitamin C is a required cofactor for collagen synthesis in the body. Providing both the raw materials and the necessary vitamin together makes biological sense, though direct comparative studies are limited.

The regulatory perspective on collagen and protein

The FDA position on collagen as protein reflects PDCAAS methodology. Because collagen scores zero, it cannot contribute to the percent daily value for protein on nutrition labels. This creates the odd situation where collagen supplements list protein grams but not percent daily value.

This regulatory framework was designed to prevent misleading claims about protein quality. Without such rules, manufacturers could market any amino acid-containing substance as a protein source regardless of nutritional value. The zero score for collagen prevents it from being positioned as equivalent to complete proteins.

Some industry advocates argue that PDCAAS unfairly penalizes collagen. The scoring system was designed around growth requirements for infants and children. Adults have different needs. Conditionally essential amino acids like glycine may be more important for adult health than PDCAAS credits.

The DIAAS alternative

A newer scoring system called DIAAS, Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score, has been proposed as a more nuanced replacement for PDCAAS. This system measures individual amino acid digestibility at the ileum rather than overall protein digestibility, providing more accurate assessments.

Under DIAAS, collagen would still score poorly due to missing tryptophan. However, DIAAS allows for meaningful scores above zero when a protein is consumed alongside complementary proteins. This better reflects how people actually eat, rarely consuming single proteins in isolation.

DIAAS adoption has been slow. PDCAAS remains the standard for regulatory purposes. But the scientific discussion has moved toward acknowledging that protein quality is context-dependent and that collagen has value despite its PDCAAS limitations.

What the nutrition label means

When you see a collagen supplement listing 10 grams of protein per serving with no percent daily value, this reflects the regulatory reality. The protein grams are accurate; collagen is indeed composed of amino acids that count as protein by basic definition.

The missing percent daily value indicates that this protein cannot, by regulatory standards, contribute to meeting protein requirements. This protects consumers from thinking collagen alone could meet their needs.

For practical purposes, you can count those grams toward your total intake while understanding they do not replace complete proteins. Track them, but ensure you meet essential amino acid needs through other sources.

Collagen benefits beyond protein contribution

Focusing solely on whether collagen counts as protein misses much of what makes collagen supplementation valuable. The specific amino acids and bioactive peptides in collagen provide benefits that PDCAAS completely ignores.

Clinical research has documented collagen benefits for skin, joints, bones, gut health, and connective tissue repair. These effects result from collagen unique composition, not from general protein provision.

Skin health evidence

Multiple randomized controlled trials have found that collagen supplementation improves skin hydration, elasticity, and wrinkle appearance. A meta-analysis of 19 studies concluded that hydrolyzed collagen supplementation improved skin hydration after 8 weeks and skin elasticity after 12 weeks compared to placebo.

The mechanism involves stimulating fibroblasts, the cells that produce collagen in skin. Bioactive peptides formed during collagen digestion signal these cells to increase collagen production. The effect is not simply providing raw materials but triggering cellular responses.

Doses as low as 2.5 grams daily have shown skin benefits in controlled trials. This makes skin improvement one of the most accessible collagen applications, requiring only modest supplementation amounts.

Joint health evidence

Athletes with exercise-induced joint pain and individuals with osteoarthritis have both shown improvements with collagen supplementation. Studies typically used 10 grams of hydrolyzed collagen daily for 3-6 months.

One study found that athletes taking 10 grams of collagen hydrolysate daily for 24 weeks experienced significant improvement in joint pain during rest, walking, standing, carrying objects, and lifting compared to placebo.

For osteoarthritis, research suggests collagen peptides may help maintain cartilage structure and reduce inflammation. The effects are modest but consistent across multiple trials. Collagen supplementation appears most beneficial for mild to moderate joint issues rather than severe degeneration.

Gut health potential

Collagen high glycine content may support gut health through multiple mechanisms. Glycine is anti-inflammatory and supports the integrity of the intestinal lining. People with compromised gut barriers may benefit from increased glycine intake.

The research here is less robust than for skin and joints. Most evidence comes from cell studies and animal research rather than human clinical trials. However, the theoretical basis is sound, and anecdotal reports of gut improvement with collagen supplementation are common.

Traditional cultures that consumed whole animals, including collagen-rich connective tissues, had lower rates of many inflammatory conditions. While this does not prove causation, it suggests potential benefits from returning collagen to modern diets.

Bone density research

Collagen makes up about 90% of bone organic matrix. Declining collagen contributes to bone fragility with aging. Supplementation may help maintain bone density, though research is still developing.

A study in postmenopausal women found that 5 grams of specific collagen peptides daily for 12 months increased bone mineral density in the spine and femoral neck compared to placebo. Another study showed improved bone formation markers with collagen supplementation.

These findings are preliminary but promising. Collagen supplementation might complement other bone health strategies including calcium, vitamin D, and weight-bearing exercise.

How to count collagen in your daily protein intake

Given everything above, here is a practical framework for incorporating collagen into protein tracking.

First, determine your total protein needs. General guidelines suggest 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight as a minimum for sedentary adults. Active individuals benefit from 1.2-2.0 grams per kilogram depending on training intensity and goals. Athletes focused on muscle building typically target the higher end.

Second, calculate your essential amino acid requirements implicitly. If you consume adequate complete proteins from meat, fish, dairy, eggs, or complementary plant sources, you will meet essential amino acid needs. Aim for the majority of your protein from these sources.

Third, add collagen for its specific benefits. Most people benefit from 10-15 grams daily. This amount supports skin, joints, and connective tissue without displacing significant amounts of complete protein.

Fourth, count the collagen toward your total. Those 10-15 grams are real protein that your body will digest, absorb, and use. They provide amino acids that have nutritional value. Just understand that they do not substitute for complete proteins in supporting muscle building or other essential amino acid-dependent functions.

Example calculation

A 70-kilogram person aiming for 1.5 grams per kilogram needs 105 grams of protein daily. They take 15 grams of collagen each morning.

Those 15 grams represent about 14% of their total protein, well under the 36% threshold. They need 90 grams of additional protein from complete sources to meet their target.

If they eat 30 grams of protein at each of three meals from sources like chicken, fish, eggs, dairy, or legumes plus complementary grains, they exceed their complete protein needs while gaining collagen benefits.

The collagen contributes to the 105-gram total. It does not replace the need for complete proteins but adds to overall intake while providing specialized amino acids.

Special considerations for athletes

Athletes with very high protein requirements should be more careful about collagen proportion. Someone eating 200 grams of protein daily could theoretically take 72 grams of collagen under the 36% rule. But they have higher essential amino acid needs for muscle repair and building.

A more conservative approach limits collagen to 10-15% of total protein intake for athletes. This ensures adequate complete proteins while still capturing collagen connective tissue benefits.

Timing also matters more for athletes. Taking collagen before training when it can support connective tissue adaptation, and taking complete proteins after training when muscle protein synthesis is elevated, optimizes both pathways.

Comparing collagen sources and types

Not all collagen supplements are identical. Different sources provide different collagen types, and processing methods affect bioavailability. Understanding these differences helps you choose effective products.

Collagen types explained

The human body contains at least 28 different collagen types. Three types dominate supplementation discussions.

Type I collagen is most abundant in the body, found in skin, bones, tendons, and connective tissue. Most collagen supplements contain primarily type I. It provides the amino acid profile discussed throughout this guide.

Type II collagen is concentrated in cartilage. Supplements targeting joint health sometimes focus on type II, either as hydrolyzed peptides or undenatured collagen. Undenatured type II collagen works through immune mechanisms rather than providing amino acids, using much smaller doses around 40 milligrams.

Type III collagen is found alongside type I in skin and blood vessels. Supplements containing type I typically also contain some type III.

For general supplementation including skin, joint, and connective tissue support, type I and III collagen peptides provide the broadest benefits. For specific cartilage support, type II products may offer advantages.

Bovine versus marine collagen

Bovine collagen from cattle provides primarily types I and III. It is widely available and typically less expensive than marine options. The amino acid profile supports skin, bone, and general connective tissue health.

Marine collagen from fish provides primarily type I. Some research suggests marine collagen peptides have smaller molecular weight and potentially better absorption. Fish collagen is also suitable for people avoiding bovine products for religious or dietary reasons.

Both sources provide similar amino acid profiles. The choice between them often comes down to personal preference, sustainability concerns, or dietary restrictions rather than meaningful efficacy differences.

Hydrolyzed versus undenatured

Most collagen supplements use hydrolyzed collagen, also called collagen peptides or collagen hydrolysate. Enzymatic processing breaks collagen into small peptides that dissolve easily and absorb efficiently. These products provide amino acids and bioactive peptides to support collagen synthesis throughout the body.

Undenatured collagen maintains its triple-helix structure. Type II undenatured collagen works by oral tolerance mechanisms, training the immune system not to attack cartilage. This requires much smaller doses and has different effects than hydrolyzed collagen.

For counting toward protein intake, hydrolyzed collagen is what you want. Undenatured collagen products use milligram doses that do not meaningfully contribute to protein intake.

Common mistakes when using collagen for protein

Understanding how to properly incorporate collagen into a protein-focused diet helps avoid common errors that undermine nutrition goals.

Mistake: replacing complete proteins with collagen

The biggest error is substituting collagen for complete proteins, especially when muscle building is a goal. Someone who normally eats 150 grams of complete protein might think switching 50 grams to collagen saves money or adds variety. This substitution would impair muscle protein synthesis and could lead to essential amino acid insufficiency over time.

Collagen should add to your protein intake, not replace quality sources. Treat it as a specialized supplement, not a primary protein source.

Mistake: counting collagen toward muscle building protein

Related but distinct is the error of counting collagen toward post-workout protein targets. If you need 30 grams of protein after training to optimize muscle protein synthesis, 15 grams of collagen plus 15 grams of whey does not provide the same stimulus as 30 grams of whey.

Take complete protein around workouts. Take collagen at other times, or before training specifically for connective tissue support.

Mistake: ignoring total protein

Some people take collagen for skin or joint benefits without considering overall protein intake. If total protein is inadequate, the body will use collagen amino acids for general protein needs rather than directing them to specialized tissues.

Adequate total protein provides the foundation. Collagen supplementation optimizes specific outcomes on top of that foundation. Without the foundation, collagen benefits may be reduced.

Mistake: excessive collagen intake

More is not always better. Taking 30-40 grams of collagen daily to maximize skin benefits does not produce better results than 10 grams in most research. Meanwhile, excessive collagen could displace appetite for complete proteins and provide excessive glycine relative to other amino acids.

Stick to evidence-based doses. For most people, 10-15 grams daily provides optimal benefits without downsides.

Research studies on collagen and protein nutrition

Let me walk through some of the key research that informs our understanding of collagen role in protein nutrition.

The 36% study

Published in Nutrients in 2019, this study by researchers in the Netherlands systematically calculated how much collagen could replace other dietary proteins while maintaining adequate essential amino acid intake. Using iterative PDCAAS calculations against the standard American diet, they found the 36% threshold.

This study validated that collagen can meaningfully contribute to protein intake within a mixed diet. It also established that typical supplementation doses of 2.5-15 grams fall well below any threshold of concern.

Whey versus collagen muscle studies

Research from 2022 published in the International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism directly compared whey protein and leucine-matched collagen peptides during resistance training. Despite equivalent leucine content, whey produced superior muscle thickness gains.

A 2022 study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition examined muscle protein synthesis in older women. Whey stimulated synthesis significantly in both resting and exercising conditions. Collagen stimulated synthesis only with exercise, and to a lesser degree.

These studies establish clear hierarchies for muscle building purposes. Complete proteins outperform collagen regardless of leucine matching.

Skin and joint clinical trials

Dozens of randomized controlled trials have examined collagen for skin and joint outcomes. A 2019 systematic review identified 11 studies with 805 participants showing beneficial effects on skin aging. A 2017 review of joint research found consistent improvements in osteoarthritis symptoms across multiple trials.

These studies demonstrate that collagen has real, clinically validated benefits beyond simple protein provision. The specialized amino acid profile produces effects that complete proteins do not.

Limitations of current research

Most collagen research has been funded by supplement manufacturers. While this does not invalidate findings, it creates potential for publication bias where positive results are more likely published than negative ones.

Many studies are also relatively small, with participant numbers in the dozens rather than hundreds. Larger, independently funded trials would strengthen confidence in collagen benefits.

The research does establish plausibility and safety of collagen supplementation. People should maintain realistic expectations while recognizing that something works even if we do not fully understand all mechanisms.

Integrating collagen with other supplements

Collagen works well as part of a broader supplementation strategy. Understanding interactions helps optimize results.

Collagen and vitamin C

Vitamin C serves as a required cofactor for collagen synthesis in the body. Without adequate vitamin C, the body cannot properly form collagen fibers even with abundant amino acid availability.

Taking collagen with vitamin C ensures both raw materials and synthesis machinery are available. Many collagen supplements include vitamin C for this reason. If yours does not, consuming it with vitamin C-rich foods or a supplement makes sense.

Research on tendon adaptation specifically used 15 grams of collagen with 200 milligrams of vitamin C before exercise, showing enhanced collagen synthesis in tendons.

Collagen and other proteins

There is no problem taking collagen alongside whey, casein, or other protein supplements. They serve different purposes and do not interfere with each other absorption or utilization.

Some athletes use a combination approach: whey protein after training for muscle protein synthesis, collagen before training for connective tissue support. This timing strategy addresses both muscle and tendon adaptation needs.

Collagen and bone health supplements

For bone health, collagen complements calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Calcium provides mineral content while collagen provides the organic matrix that gives bones flexibility and resistance to fracture.

Some research suggests collagen may improve calcium absorption and retention, though this needs further study. At minimum, there are no negative interactions between collagen and bone health supplements.

Collagen and hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid supports skin hydration through different mechanisms than collagen. Some supplements combine both for comprehensive skin support. There are no known interactions, and the combination may produce complementary benefits.

Signs you might benefit from collagen supplementation

While most people can benefit from collagen, certain signs suggest you might see more pronounced effects.

Declining skin quality

If your skin is becoming thinner, less elastic, or showing more wrinkles despite good skincare habits, declining collagen production may be involved. Supplementation can provide building blocks and signals to maintain skin collagen synthesis.

People over 30 generally experience declining natural collagen production. This makes supplementation increasingly relevant with age, particularly for those concerned about skin aging.

Joint discomfort during exercise

Exercise-induced joint pain, stiffness, or discomfort may indicate connective tissue that could benefit from additional support. Athletes and active individuals often report improvements in joint comfort with regular collagen use.

This differs from acute injury, which requires proper medical evaluation. Collagen supports joint maintenance and mild discomfort, not treatment of injuries or disease.

Low glycine intake

If your diet consists primarily of muscle meats with little connective tissue, bone broth, or organ meats, you may have suboptimal glycine intake. Modern diets often lack the collagen-rich foods our ancestors consumed regularly.

Vegetarians and vegans particularly lack dietary collagen sources. While they cannot use most collagen supplements due to animal origins, this indicates their glycine intake may be low.

Poor gut health

While research is still developing, people with gut issues including increased intestinal permeability may benefit from collagen glycine content. Glycine supports the intestinal lining and has anti-inflammatory properties.

This is not a substitute for proper gut health protocols, but collagen supplementation may complement other interventions.

Slow recovery from exercise

If your tendons and ligaments seem to recover more slowly than your muscles after intense training, connective tissue support may help. Collagen provides specific amino acids that muscles do not need in the same proportions.

Athletes training connective-tissue-intensive activities like jumping, sprinting, or heavy resistance training may particularly benefit from targeted collagen supplementation.

Frequently asked questions

Does collagen count as protein for keto macros?

Yes, collagen peptides count toward protein macros on a ketogenic diet. Each gram of collagen protein contributes approximately 4 calories, just like other proteins. The lack of carbohydrates in pure collagen supplements makes them keto-compatible. However, you should still meet essential amino acid needs through complete proteins like meat, eggs, and dairy, which are already keto staples.

Can I use collagen as my only protein source?

No. Collagen lacks tryptophan entirely and has insufficient amounts of other essential amino acids. Using collagen as your only protein source would lead to essential amino acid deficiency, impairing muscle maintenance, immune function, and numerous metabolic processes. Collagen should complement, not replace, complete protein sources.

Does collagen break a fast?

Yes, collagen contains calories and amino acids that trigger metabolic responses. Taking collagen during a fasting window technically ends the fast. If you practice intermittent fasting for metabolic benefits, consume collagen during your eating window. Some people find that small amounts of collagen do not significantly disrupt their fasting goals, but this is individual and depends on your specific fasting objectives.

How long does it take to see results from collagen?

Skin benefits typically appear after 8-12 weeks of consistent supplementation. Joint benefits may take 3-6 months to become noticeable. Collagen effects accumulate gradually as the body incorporates new collagen into tissues. Patience and consistency matter more than high doses.

Is marine collagen better than bovine collagen?

Neither is definitively better. Marine collagen may have slightly smaller peptides that absorb efficiently, while bovine collagen provides types I and III compared to mainly type I from fish. Both provide similar amino acid profiles. Choose based on dietary preferences, sustainability concerns, or allergen considerations rather than expecting significant efficacy differences.

Can vegetarians take collagen supplements?

Traditional collagen supplements come from animal sources and are not vegetarian. Some products marketed as vegan collagen boosters contain amino acids and nutrients that support collagen production but are not actual collagen. Vegetarians concerned about collagen can focus on vitamin C, zinc, copper, and amino acids from plant sources to support endogenous collagen synthesis.

Should I take collagen before or after workouts?

For connective tissue benefits, research suggests taking collagen 30-60 minutes before exercise with vitamin C. This timing delivers amino acids when connective tissue blood flow increases during activity. For general benefits unrelated to exercise, timing matters less. Consistency matters more than any specific timing protocol.

Does collagen help with weight loss?

Collagen has no direct fat-burning properties. However, protein in general supports satiety, and some people find collagen helps them feel fuller. The effect is modest and not unique to collagen. For weight loss, focus on overall calorie balance and adequate protein from complete sources rather than expecting collagen to drive results.

External resources

For researchers serious about optimizing their peptide protocols, SeekPeptides provides the most comprehensive resource available, with evidence-based guides, proven protocols, and a community of thousands who have navigated these exact questions.

In case I do not see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night. May your proteins stay complete, your collagen stay abundant, and your amino acids stay balanced.