Jan 27, 2026

Of the estimated 10 million bioactive peptides contained within spider venoms worldwide, fewer than 0.01 percent have been characterized by researchers. That number deserves a moment of consideration. Ten million peptides. Millions of years of evolutionary refinement have produced molecular tools so precise that they can distinguish between nearly identical protein targets, so potent that nanomolar concentrations trigger measurable effects, and so stable that they survive conditions that would destroy most biological molecules. Yet we have barely scratched the surface of what these compounds might offer.

The phrase spider venom typically evokes images of pain and danger. Fair enough. These venoms evolved specifically to incapacitate prey and deter predators. But that same evolutionary pressure created something remarkable: a library of peptides pre-optimized through natural selection for high affinity, selectivity, and stability. Pharmaceutical companies spend billions trying to engineer molecules with these exact properties. Nature has already done the work.

Understanding peptide structure and function requires examining these venom-derived compounds closely. Spider venom peptides represent some of the most sophisticated molecular machinery found anywhere in biology, targeting pain pathways, cancer cell membranes, bacterial infections, and neurological processes with surgical precision. This guide examines what makes these peptides unique, how they work, which ones show therapeutic promise, and why they matter for the broader field of peptide research.

The therapeutic potential extends far beyond academic curiosity. Researchers have identified spider venom peptides that could treat chronic pain more effectively than morphine with fewer side effects, kill cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue, combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and protect brain tissue from stroke damage. Some of these applications have moved beyond laboratory studies into preclinical development. SeekPeptides tracks these developments as part of our commitment to comprehensive peptide education, helping researchers understand both established compounds and emerging areas of investigation.

What makes spider venom peptides unique

Spider venoms are not single substances. They are complex cocktails containing hundreds to thousands of different compounds, primarily bioactive peptides. A single spider species might produce 200 to 500 distinct peptide toxins, each targeting different molecular systems. Across the roughly 49,000 known spider species, the total number of unique venom peptides likely exceeds 10 million. This represents one of the largest untapped sources of pharmacologically active molecules on the planet.

Three features distinguish spider venom peptides from other peptide families.

First, evolutionary optimization. These peptides have been refined over approximately 400 million years of spider evolution. Natural selection favored peptides that worked quickly, specifically, and reliably. Peptides that failed to incapacitate prey or defend against predators were eliminated from the gene pool. What remains represents the survivors of the most rigorous drug development program imaginable, one conducted across geological timescales with life and death as the success metrics.

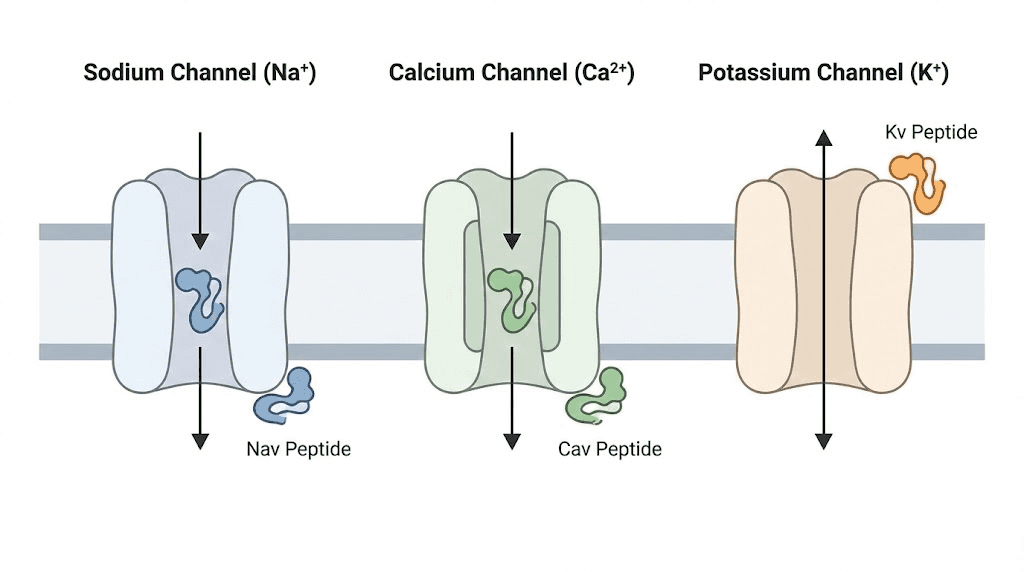

Second, target diversity. Spider prey includes insects, other spiders, small vertebrates, and occasionally larger animals. This diversity of targets created selection pressure for peptides affecting many different molecular systems. Different spider species evolved peptides targeting sodium channels, potassium channels, calcium channels, acid-sensing ion channels, mechanosensitive channels, and various receptors. This molecular diversity provides researchers with tools for studying nearly every aspect of neurological function.

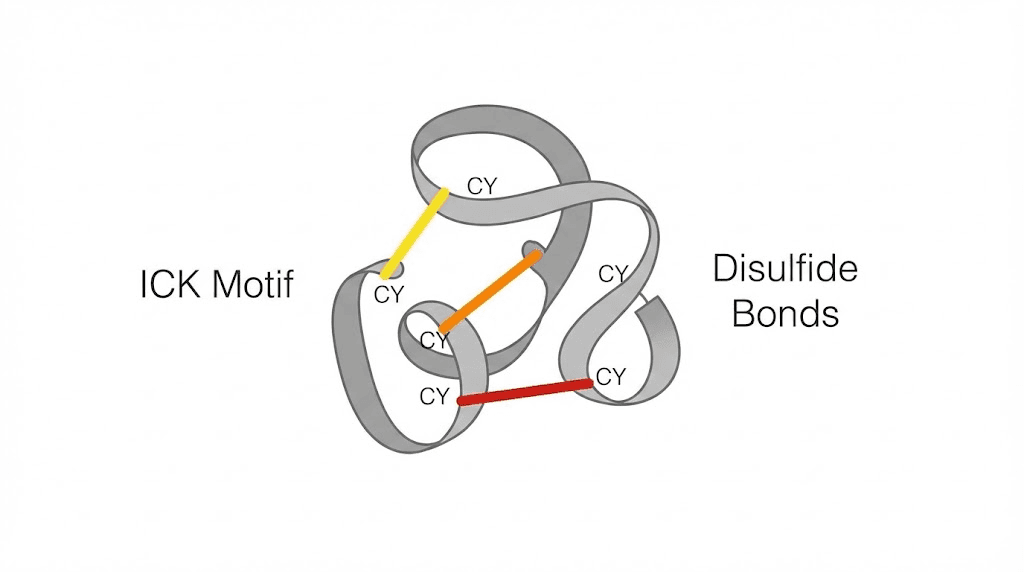

Third, structural stability. Most spider venom peptides contain a distinctive molecular architecture called the inhibitor cystine knot, or ICK motif. This structure involves three disulfide bonds arranged in a specific pattern that creates extraordinary stability. ICK peptides resist degradation by proteases, remain stable across wide pH ranges, and maintain their activity under conditions that would denature most proteins. This stability makes them attractive candidates for therapeutic development, addressing one of the major challenges in peptide drug delivery.

Comparison with other venom peptides

Spider venom peptides share some characteristics with peptides from other venomous animals but differ in important ways. Cone snail venoms, for example, produced ziconotide (Prialt), the only venom-derived peptide currently approved for treating pain. Cone snail peptides tend to be smaller and more rigid than spider peptides, making them easier to synthesize but potentially limiting their target diversity.

Snake venoms contain peptides and larger proteins with potent effects on blood clotting and blood pressure. These have yielded drugs like captopril for hypertension. However, snake venom components are often larger and more immunogenic than spider peptides, complicating their therapeutic development.

Scorpion venoms contain peptides similar to spider venoms in structure and function, which makes sense given the evolutionary relationship between these arachnids. Both scorpion and spider venoms contain numerous ICK peptides targeting ion channels. Research on both venom types often proceeds in parallel, with findings from one informing work on the other.

The table below compares key features across venom sources used in peptide research.

Venom Source | Typical Peptide Size | Primary Targets | Structural Stability | Approved Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Spiders | 3 to 10 kDa | Ion channels, receptors | Very high (ICK motif) | None yet (several in development) |

Cone snails | 1 to 4 kDa | Ion channels, receptors | High (disulfide-rich) | Ziconotide (Prialt) |

Scorpions | 3 to 8 kDa | Ion channels | Very high (ICK motif) | Chlorotoxin conjugate in trials |

Snakes | 5 to 50 kDa | Blood proteins, receptors | Variable | Captopril derivatives, eptifibatide |

Major categories of spider venom peptides

Researchers classify spider venom peptides based on their molecular targets, their source spider family, or their structural features. The most practical classification for understanding therapeutic potential focuses on molecular targets. Below are the major categories receiving research attention for their relevance to tissue repair, inflammation, and other therapeutic applications.

Sodium channel modulators

Voltage-gated sodium channels control electrical signaling in nerves and muscles. They are essential for everything from pain sensation to heartbeat regulation to muscle contraction. Different sodium channel subtypes (Nav1.1 through Nav1.9) serve different functions, and mutations in these channels cause conditions ranging from epilepsy to chronic pain syndromes to cardiac arrhythmias.

Spider venoms contain numerous peptides targeting sodium channels with remarkable selectivity. Some peptides activate specific channel subtypes, keeping them open longer than normal. Others inhibit channels, preventing them from opening. This bidirectional control, combined with subtype selectivity, makes sodium channel-targeting spider peptides valuable both as research tools and as potential therapeutics.

The peptide Hm1a from the Togo starburst tarantula selectively activates Nav1.1 channels. This might seem counterproductive for drug development, since activating sodium channels typically increases neuronal excitability. However, Nav1.1 is primarily expressed in inhibitory interneurons. Activating these channels actually reduces overall brain excitability, which is why Hm1a shows promise for treating Dravet syndrome, a severe form of childhood epilepsy characterized by Nav1.1 dysfunction.

Meanwhile, peptides that selectively inhibit Nav1.7 channels attract intense interest for pain treatment. Nav1.7 plays a critical role in pain signal transmission. People with loss-of-function mutations in Nav1.7 are unable to feel pain, while gain-of-function mutations cause severe chronic pain conditions. A selective Nav1.7 inhibitor could theoretically eliminate pain without the addiction potential, respiratory depression, or tolerance development associated with opioids.

Several spider venom peptides inhibit Nav1.7 with high potency and selectivity. The peptide Pn3a from the tarantula Pamphobeteus nigricolor inhibits Nav1.7 with an IC50 of 0.9 nanomolar and shows at least 40 to 1000 fold selectivity over other sodium channel subtypes. This exquisite selectivity makes Pn3a a valuable tool for studying Nav1.7 function and a potential lead compound for pain therapeutic development.

Calcium channel modulators

Voltage-gated calcium channels regulate neurotransmitter release, muscle contraction, hormone secretion, and gene expression. Like sodium channels, calcium channels come in multiple subtypes (Cav1.1 through Cav3.3) with distinct tissue distributions and functions.

Spider venom peptides targeting N-type calcium channels (Cav2.2) hold particular therapeutic interest. Cav2.2 channels localize to nerve terminals where they trigger neurotransmitter release. Blocking these channels reduces the release of pain-signaling molecules like glutamate, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide. This is exactly the mechanism by which ziconotide, the cone snail peptide, provides pain relief in patients who do not respond to other treatments.

The spider peptide PnTx3-6 from the Brazilian armed spider (Phoneutria nigriventer) blocks Cav2.2 channels with high potency. Studies comparing PnTx3-6 with morphine and ziconotide found it more effective with fewer side effects in certain pain models. Unlike ziconotide, which requires intrathecal administration, researchers are exploring whether modified versions of spider calcium channel blockers might work through less invasive delivery routes.

T-type calcium channels (Cav3.1 through Cav3.3) also represent important targets. These channels contribute to certain types of chronic pain, particularly visceral pain and pain from irritable bowel syndrome. A spider venom peptide that inhibits both Nav channels and Cav3 channels has shown efficacy in animal models of IBS-related pain, suggesting combination targeting of multiple ion channels might provide superior gut health benefits.

Potassium channel modulators

Potassium channels are the most diverse family of ion channels, with over 80 genes encoding different subtypes in humans. They regulate membrane potential, neuronal excitability, muscle contraction, hormone secretion, and cell volume. Dysfunctional potassium channels contribute to epilepsy, cardiac arrhythmias, diabetes, and autoimmune diseases.

Spider venom peptides that block specific potassium channel subtypes serve as important research tools. By applying a peptide that blocks a particular channel subtype, researchers can determine what functions that channel normally performs. This approach has revealed roles for specific potassium channels in brain function, cardiac rhythm, and immune cell activation.

Therapeutically, potassium channel-blocking peptides show promise for conditions including multiple sclerosis. Kv1.3 channels are highly expressed on autoreactive T cells that drive autoimmune inflammation. Blocking these channels selectively suppresses pathogenic T cells without broadly impairing immune function. Several spider and scorpion venom peptides target Kv1.3 with high selectivity, providing leads for autoimmune disease treatment.

Acid-sensing ion channel modulators

Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) respond to decreases in extracellular pH. They contribute to pain sensation during tissue injury, ischemic stroke damage, and cancer progression. The spider peptide PcTx1 from the Trinidad chevron tarantula (Psalmopoeus cambridgei) potently inhibits ASIC1a channels.

In animal studies, PcTx1 produced antinociceptive effects comparable to morphine in various pain models. The peptide demonstrated particular efficacy in inflammatory pain and neuropathic pain models. Additionally, ASIC1a channels contribute to neuronal damage during stroke when tissue pH drops due to reduced blood flow. PcTx1 shows neuroprotective effects in stroke models, reducing brain damage when administered after ischemic injury.

Cancer research has revealed that ASIC1a expression is altered in gliomas (brain tumors). Inhibiting ASIC1a with PcTx1 reduces the proliferation and migration of glioma cells, suggesting potential anticancer applications. This intersection of pain research and peptide stacking strategies exemplifies how spider venom peptides might address multiple therapeutic goals simultaneously.

Mechanosensitive channel modulators

Mechanosensitive ion channels convert physical force into electrical signals. They underlie our sense of touch, balance, and proprioception. They also contribute to various disease states when their function becomes dysregulated.

GsMTx4 from the Chilean rose tarantula (Grammostola spatulata) stands out as the only specific inhibitor of mechanosensitive channels available to researchers. This peptide inhibits Piezo1 channels and certain TRP channels involved in mechanotransduction. Despite being isolated from venom, GsMTx4 is non-toxic to mice at research doses.

GsMTx4 has proven valuable for studying mechanosensitive channel function in multiple contexts. Research applications include studying cardiac arrhythmias (mechanical stretch can trigger dangerous heart rhythms), investigating bladder dysfunction (mechanosensitive channels in bladder wall regulate urinary function), examining pain pathways (mechanical hyperalgesia involves mechanosensitive channel activation), and understanding bone formation (Piezo1 contributes to bone mechanosensation).

Notably, GsMTx4 inhibition is not stereospecific, meaning both left-handed and right-handed versions of the peptide work equally well. This unusual property suggests the peptide acts on the lipid membrane surrounding channels rather than directly on channel proteins, providing insights into an entirely different mechanism of channel modulation.

Latrotoxins: the black widow toxin family

When discussing spider venom peptides, latrotoxins deserve special attention. These are not small peptides like the ICK toxins described above but rather large proteins (approximately 130 kDa) found in black widow spider (Latrodectus) venom. They remain relevant to peptide research because they provided foundational insights into neurotransmitter release mechanisms and continue to serve as tools for neurological research.

The latrotoxin family includes several members targeting different organisms. Alpha-latrotoxin targets vertebrates and causes the clinical syndrome of latrodectism following black widow bites. Alpha-latroinsectotoxin (LTQ) targets insects. Alpha-latrocrustatoxin targets crustaceans. This target specificity allows researchers to study neurotransmitter release in different systems using appropriate latrotoxin variants.

Alpha-latrotoxin works by binding to specific receptors on nerve terminals: neurexin (which requires calcium) and latrophilin (which does not require calcium). After binding, the toxin inserts into the membrane and forms a pore that allows calcium and other ions to flow into the nerve terminal. This triggers massive release of neurotransmitters, depleting the nerve terminal and causing the muscle spasms and pain characteristic of black widow envenomation.

Understanding latrotoxin mechanisms led to the discovery of neurexins and latrophilins, which turned out to be important synaptic proteins beyond their role as toxin receptors. Neurexins are now known to be essential for proper synapse formation and function. Mutations in neurexin genes contribute to autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Latrophilins regulate brain development and neural circuit formation.

The research continues to yield insights. A 2021 study determined the complete molecular structure of alpha-latrotoxin, revealing how four toxin molecules assemble into the pore-forming complex. This structural information may eventually enable researchers to design compounds that block latrotoxin action, potentially providing treatments for severe black widow envenomation beyond the current antivenom approach.

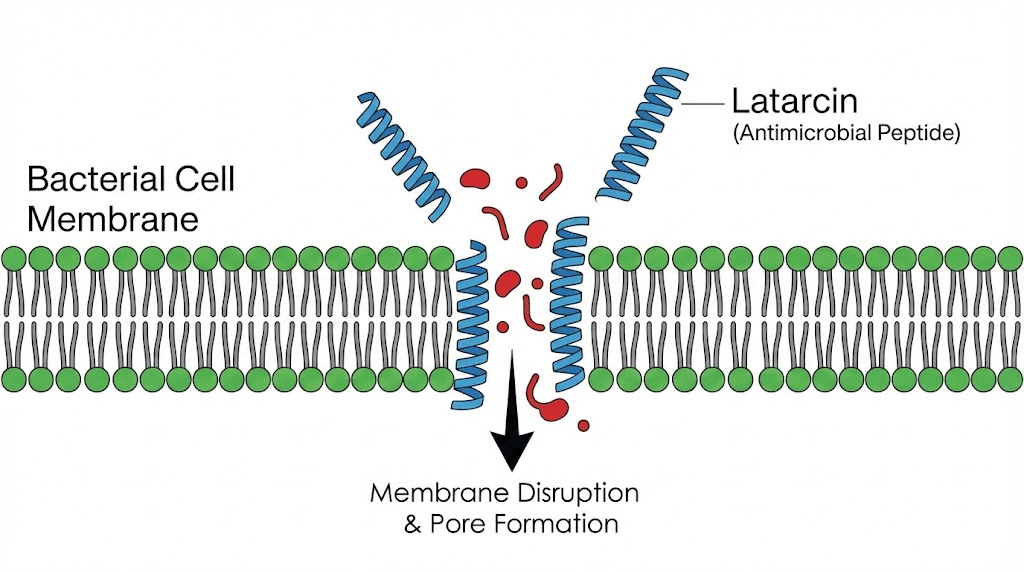

Latarcins: antimicrobial peptides from spider venom

Not all therapeutically interesting spider venom peptides target ion channels. Latarcins are a family of antimicrobial peptides from the venom of the spider Lachesana tarabaevi. These linear peptides (lacking the ICK motif common to most spider venom peptides) kill bacteria, fungi, and cancer cells through membrane disruption.

Seven latarcin peptides (Ltc1 through Ltc7) have been characterized, each with slightly different properties. Latarcin 2a (Ltc2a) stands out for its broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and relatively low toxicity to mammalian cells. The peptide adopts an alpha-helical structure when it contacts cell membranes, with one side of the helix being hydrophobic (water-repelling) and the other being hydrophilic (water-attracting). This amphipathic structure allows the peptide to insert into bacterial membranes and disrupt their integrity.

In the context of increasing antibiotic resistance, antimicrobial peptides like latarcins offer potential alternatives to conventional antibiotics. Bacteria find it much harder to develop resistance to membrane-disrupting peptides than to antibiotics that target specific bacterial proteins. The mechanism is too fundamental and too rapid for typical resistance mutations to overcome.

Recent research has expanded latarcin applications beyond antimicrobial uses. A 2025 study published in Biomaterials Advances examined Ltc2a as an anticancer agent against triple-negative breast cancer. The peptide showed selective cytotoxicity toward cancer cells at concentrations that did not harm normal cells. Mechanistic studies revealed that Ltc2a disrupts cancer cell membranes within one hour of exposure, triggering rapid cell death.

In vivo studies using zebrafish models demonstrated favorable uptake and minimal acute toxicity, with 80 percent survival at effective anticancer concentrations. These findings position Ltc2a as a potential dual-purpose therapeutic: antimicrobial for infection and cytotoxic for cancer, with selectivity that could spare healthy tissues.

Spider venom peptides for pain treatment

Chronic pain affects approximately 15 percent of the adult population globally. Current treatments, particularly opioids, carry significant risks including addiction, tolerance, respiratory depression, and death from overdose. The need for new pain treatment options drives much of the research into spider venom peptides.

Spider venom peptides offer several advantages for pain treatment. They target specific molecular pathways involved in pain signaling rather than broadly suppressing central nervous system function like opioids. Many spider peptides show no evidence of tolerance development in long-term studies. Their mechanisms do not involve opioid receptors, eliminating addiction potential. And some spider peptides have shown efficacy in pain types that respond poorly to existing treatments.

Targeting Nav1.7 for pain

The case for Nav1.7 as a pain target comes from human genetics. People born without functional Nav1.7 channels cannot feel pain but have no other obvious deficits. Conversely, people with gain-of-function Nav1.7 mutations experience severe chronic pain syndromes. This suggests that blocking Nav1.7 should eliminate pain without causing the sedation, cognitive impairment, or respiratory depression associated with centrally-acting analgesics.

Multiple spider venom peptides inhibit Nav1.7 with varying degrees of potency and selectivity. The challenge has been finding peptides selective enough to block Nav1.7 without affecting Nav1.5 (which controls heartbeat) or Nav1.4 (which controls skeletal muscle). The high sequence similarity between sodium channel subtypes makes this difficult, but several spider peptides have achieved the necessary selectivity.

Pn3a, mentioned earlier, represents one of the most selective Nav1.7 inhibitors known. Studies have demonstrated its utility as a pharmacological tool for determining which pain behaviors depend on Nav1.7 function. While questions remain about whether Pn3a alone provides analgesia (pain relief may require blocking additional targets), it establishes proof of concept for highly selective Nav1.7 targeting.

Multi-target approaches

Some researchers argue that effective pain treatment requires blocking multiple targets simultaneously. Pain signaling involves many molecular players, and blocking just one may allow compensatory pathways to maintain pain transmission. Spider venoms naturally contain peptides targeting multiple systems, suggesting evolution may have already solved this problem.

One spider venom peptide with multi-target activity has shown efficacy in animal models of irritable bowel syndrome pain. By inhibiting both Nav channels and Cav3 (T-type) calcium channels, this peptide blocks pain signals at multiple points in the transmission pathway. The researchers noted that this combination targeting provides a novel route for treating chronic visceral pain that has resisted other approaches.

Multi-target peptides align with the peptide stacking approach used in other therapeutic contexts, where combining peptides with complementary mechanisms can produce effects greater than either peptide alone.

Advantages over existing pain medications

Comparing spider venom peptides with current pain medications reveals several potential advantages.

Versus opioids: Spider venom peptides do not act on opioid receptors, eliminating addiction potential and respiratory depression risk. They do not produce tolerance, meaning the same dose should remain effective over time. They do not cause the constipation that affects nearly all chronic opioid users.

Versus NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs work by blocking prostaglandin synthesis, which provides pain relief but also causes gastrointestinal bleeding, kidney problems, and cardiovascular risks with long-term use. Spider venom peptides act on ion channels rather than prostaglandins, avoiding these complications.

Versus ziconotide: The one venom-derived peptide already approved for pain, ziconotide, requires intrathecal administration via an implanted pump because it cannot cross the blood-brain barrier when given systemically. Some spider peptides show better penetration properties that might allow less invasive administration routes.

The challenges include delivery (peptides are generally not orally bioavailable), potential immunogenicity (the body might develop antibodies against foreign peptides), and the complexity of developing peptide therapeutics compared to small molecule drugs. However, advances in peptide modification, nasal delivery systems, and nanoparticle carriers are addressing these limitations.

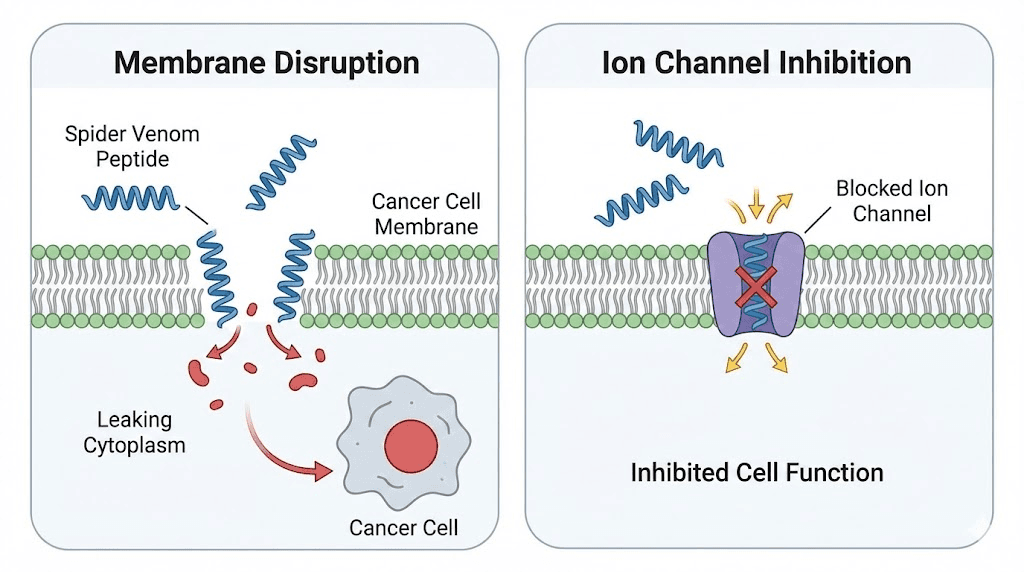

Spider venom peptides for cancer

Cancer cells differ from normal cells in ways that make them vulnerable to certain spider venom peptides. Some cancer cells overexpress specific ion channels. Many cancer cells have altered membrane compositions. Rapidly dividing cells may be more sensitive to membrane-disrupting peptides. These differences create opportunities for selective toxicity.

Ion channel targeting

Several ion channels are overexpressed in cancers and contribute to tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Nav1.5 sodium channels, for example, are highly expressed in breast cancer cells but minimally expressed in normal breast tissue. These channels promote cancer cell migration and invasion.

The spider peptide JZTX-14 inhibits Nav1.5 and has been tested against breast cancer cells. While JZTX-14 did not affect breast cancer cell proliferation, it significantly inhibited cell migration. Since metastasis (cancer spread) is responsible for most cancer deaths, agents that prevent migration without necessarily killing cells could still provide therapeutic benefit.

Similarly, the spider peptide that inhibits ASIC1a (PcTx1) reduces glioma cell proliferation and migration. Brain tumors create acidic microenvironments, and ASIC channels help cancer cells thrive in these conditions. Blocking these channels removes a survival advantage specific to cancer cells.

Membrane-disrupting peptides

Cancer cell membranes differ from normal cell membranes in several ways. They often have more negatively charged phospholipids on their outer surface, different cholesterol content, and altered membrane fluidity. Membrane-disrupting peptides like latarcins can exploit these differences to selectively kill cancer cells.

Latarcin Ltc2a shows selective cytotoxicity toward breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) and colon cancer cells (HCT 116) at concentrations that do not affect normal cells (HEK 293T). The peptide works quickly, inducing cell death within one hour through membrane disruption. This rapid action may help prevent cancer cells from developing resistance mechanisms.

Another spider venom-derived peptide, LyeTx I-b (derived from the wolf spider Lycosa erythrognatha), shows cytotoxic effects against triple-negative breast cancer cells. This cancer subtype lacks the receptors targeted by many breast cancer drugs, making it particularly difficult to treat. Spider venom peptides that work through membrane disruption rather than receptor targeting may provide options for these resistant cancers.

The spider peptide Lycosin-I from Lycosa singoriensis inhibits cancer cell growth both in laboratory studies and in animal tumor models. Mechanistic studies revealed that Lycosin-I activates the mitochondrial death pathway, triggering apoptosis (programmed cell death) in cancer cells. It also increases expression of the protein p27, which inhibits cell cycle progression. These complementary mechanisms make it harder for cancer cells to escape the peptide effects.

Advantages for cancer treatment

Spider venom peptides offer potential advantages over conventional chemotherapy. They can be highly selective for cancer cells based on membrane composition or ion channel expression. They act through physical mechanisms (membrane disruption) or channel inhibition that are difficult for cancer cells to develop resistance against. They may work against cancer types resistant to existing drugs. And they can potentially be combined with conventional treatments to enhance efficacy.

The challenges mirror those for pain applications: delivery, immunogenicity, and manufacturing complexity. Additionally, cancer treatment typically requires reaching tumors throughout the body, demanding systemic administration and good tissue penetration. Researchers are exploring nanoparticle delivery systems to improve spider peptide distribution to tumors while limiting exposure of normal tissues.

Spider venom peptides as antimicrobial agents

Antibiotic resistance represents one of the greatest threats to modern medicine. The World Health Organization estimates that drug-resistant infections kill 700,000 people annually, a number projected to reach 10 million by 2050 without new interventions. Antimicrobial peptides from spider venom offer a potential response to this crisis.

Mechanisms of antimicrobial action

Spider venom antimicrobial peptides typically kill bacteria through membrane disruption rather than by targeting specific bacterial proteins. This mechanism offers several advantages. It acts rapidly, killing bacteria within minutes rather than hours. It works against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. And bacteria find it extremely difficult to develop resistance because they would need to fundamentally alter their membrane structure.

The latarcin family demonstrates this approach well. These peptides have amphipathic structures, meaning they have both water-attracting and water-repelling regions. When they contact bacterial membranes, they insert into the lipid bilayer with their hydrophobic regions facing inward. Multiple peptide molecules accumulate in the membrane, eventually causing it to lose integrity. The bacterial contents leak out, and the cell dies.

Different latarcins show varying degrees of selectivity between bacterial and mammalian cells. Ltc1 efficiently kills bacteria while causing minimal disruption to mammalian cell membranes. Ltc2a is more broadly disruptive but shows selectivity for cancer cells over normal cells. Understanding these selectivity differences guides optimization for different applications.

Broad-spectrum activity

Spider venom antimicrobial peptides typically show activity against multiple bacterial species. Latarcin 2a, for example, kills both gram-positive bacteria (like Staphylococcus) and gram-negative bacteria (like Escherichia coli). Some spider antimicrobial peptides also show activity against fungi and parasites.

This broad-spectrum activity contrasts with many conventional antibiotics that work only against specific bacterial types. A single spider peptide might replace multiple antibiotics for treating mixed infections or infections of unknown cause. Combined with the low resistance potential, this makes spider antimicrobial peptides attractive candidates for infection treatment.

Synergy with conventional antibiotics

Research has shown that spider venom antimicrobial peptides can work synergistically with conventional antibiotics. The peptides damage bacterial membranes, making them more permeable to antibiotics that would otherwise have difficulty reaching their intracellular targets. This combination approach could extend the useful life of existing antibiotics and improve outcomes against resistant infections.

Studies combining latarcin peptides with conventional antibiotics found enhanced killing of bacteria resistant to the antibiotic alone. The membrane disruption caused by the peptide allowed the antibiotic to penetrate the bacterial cell more effectively. This synergy occurred even at sublethal peptide concentrations, suggesting combination therapies might use lower doses of both components.

Spider venom peptides for neurological conditions

Beyond pain, spider venom peptides show promise for several neurological conditions. Their high selectivity for specific ion channel subtypes makes them particularly suited for disorders involving channel dysfunction.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy involves abnormal electrical activity in the brain, often due to imbalances between excitatory and inhibitory signaling. Different epilepsy syndromes involve different molecular defects, and spider venom peptides targeting various ion channels might address specific epilepsy types.

Dravet syndrome, mentioned earlier, results from loss-of-function mutations in Nav1.1 channels. These channels are primarily expressed in inhibitory interneurons. When Nav1.1 function is reduced, inhibitory signaling decreases, allowing runaway excitation and seizures. The spider peptide Hm1a selectively activates Nav1.1, potentially restoring the inhibitory brake on brain excitation.

Studies at the University of Queensland have advanced Hm1a-based therapies toward clinical development for Dravet syndrome. The peptide represents a precision medicine approach, directly addressing the molecular defect rather than broadly suppressing brain activity like many existing anticonvulsants.

Stroke

Ischemic stroke occurs when blood supply to part of the brain is interrupted. The resulting oxygen and glucose deprivation triggers a cascade of damaging events including excess neurotransmitter release, calcium overload, and acidosis. Several spider venom peptides target processes involved in stroke damage.

PcTx1, the ASIC1a inhibitor, shows neuroprotective effects in stroke models. During ischemia, tissue pH drops as cells switch to anaerobic metabolism and produce lactic acid. ASIC1a channels open in response to this acidification, allowing calcium to enter neurons and contributing to cell death. Blocking ASIC1a with PcTx1 reduces this calcium influx and protects neurons from ischemic damage.

The GsMTx4 peptide that inhibits mechanosensitive channels has also shown stroke protection in animal models. Mechanical forces change during ischemia as cells swell from ionic imbalances. Mechanosensitive channels that respond to this swelling may contribute to damage, and blocking them with GsMTx4 reduces infarct size in experimental stroke.

Importantly, these peptides remain effective when administered after stroke onset, suggesting they might help patients even when treatment cannot begin immediately. Current stroke therapies must be given within a narrow time window, so agents effective at later timepoints would significantly expand treatment options.

Cardiac conditions

Ion channels regulate heart rhythm, and channel dysfunction causes various arrhythmias. Spider venom peptides that selectively modulate cardiac ion channels could serve as antiarrhythmic agents or as tools for studying cardiac electrophysiology.

The peptide GsMTx4 prevents certain stretch-induced arrhythmias. When heart tissue stretches abnormally (as occurs during heart attack or heart failure), mechanosensitive channels can trigger dangerous rhythm disturbances. GsMTx4 prevented myocardial infarction complications in mouse models, suggesting mechanosensitive channel inhibition might protect against post-infarct arrhythmias.

Various spider peptides targeting sodium and potassium channels in the heart are used as research tools to dissect cardiac electrophysiology. Understanding which channels contribute to specific arrhythmia types guides development of more targeted antiarrhythmic drugs.

Sources and research supply considerations

Spider venom peptides for research come from several sources. Natural extraction from spider venom provides authentic peptides but limited quantities. A single spider produces only microliters of venom, and milking spiders is labor-intensive. Natural extraction remains important for discovering new peptides and confirming that synthetic versions match natural activity.

Chemical synthesis produces peptides matching natural sequences without requiring spiders. Modern solid-phase peptide synthesis can produce most spider venom peptides, though ICK peptides with multiple disulfide bonds present challenges for correct folding. Synthesis allows production of modified peptides with potentially improved properties.

Recombinant expression in bacteria, yeast, or insect cells offers scalable production for peptides needed in larger quantities. Bacterial expression systems have successfully produced active spider venom peptides including latarcins. However, ICK peptides often require specialized expression systems to achieve correct disulfide bond formation.

Researchers interested in working with spider venom peptides typically obtain them from specialized suppliers focusing on ion channel research tools or synthesize them using established protocols published in the scientific literature. Quality testing is essential given the potency of these compounds and the importance of correct folding for activity.

For those exploring the broader peptide field, SeekPeptides provides comprehensive educational resources covering reconstitution techniques, storage requirements, and dosing considerations applicable across peptide research.

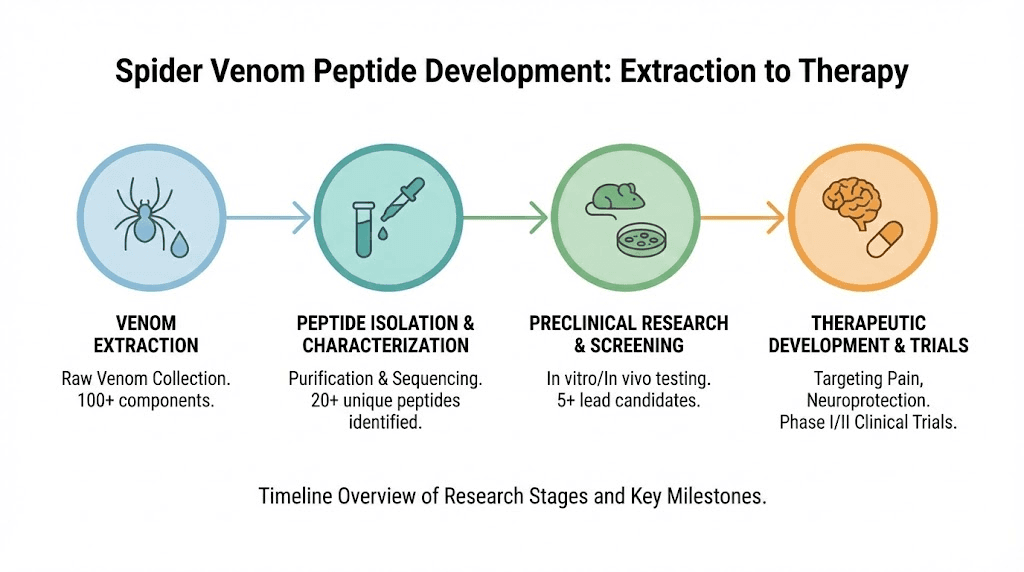

Current development status

No spider venom peptide has yet received regulatory approval for therapeutic use in humans. However, several are in various stages of development, and the pace of research has accelerated considerably in recent years.

Academic research

University laboratories worldwide continue characterizing new spider venom peptides and elucidating mechanisms of known ones. Structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy and x-ray crystallography reveal how peptides interact with their targets at atomic resolution. Functional studies in cells and animals demonstrate therapeutic potential in disease models.

The University of Queensland has been particularly active in spider venom peptide research, with programs targeting pain, epilepsy, and stroke. Their work on funnel-web spider venoms has revealed peptides with remarkable selectivity for specific sodium channel subtypes. Collaborations with pharmaceutical companies are advancing some of these peptides toward clinical development.

Biotech and pharmaceutical industry

Several companies have spider venom peptide programs at various development stages. Most details remain confidential during early development, but public information indicates active programs in pain, epilepsy, and cardiac conditions.

The broader venom-derived therapeutics space has attracted significant investment, with multiple companies pursuing peptides from various venomous animals. Success with ziconotide (from cone snails) and other venom-derived drugs has validated the approach and encouraged further development.

Key challenges

Several challenges must be overcome before spider venom peptides reach patients.

Delivery remains paramount. Peptides generally cannot be taken orally because digestive enzymes destroy them. Many cannot reach their targets after systemic injection because they do not penetrate tissues well. Researchers are developing modified peptides with better stability and tissue penetration, as well as delivery systems including nasal sprays, nanoparticles, and targeted carriers.

Manufacturing scale-up presents technical and economic challenges. Peptides are more expensive to produce than small molecule drugs. ICK peptides with multiple disulfide bonds require specialized production methods to ensure correct folding. Cost reduction through improved manufacturing processes will be essential for commercial viability.

Regulatory pathways for peptide drugs are well-established, but the potency and specificity of spider venom peptides may require particularly careful safety evaluation. Demonstrating that peptides do not produce unexpected effects on non-target channels or receptors will be important for approval.

Despite these challenges, the field continues advancing. Technological improvements in peptide synthesis, delivery systems, and analytical methods are steadily addressing historical limitations.

Comparison with traditional therapeutic peptides

Spider venom peptides differ from the therapeutic peptides most researchers encounter. Understanding these differences helps contextualize their potential roles.

Versus hormone-derived peptides

Many therapeutic peptides are analogs of natural hormones: insulin for diabetes, growth hormone-releasing peptides for hormone optimization, and somatostatin analogs for various conditions. These work by mimicking or modifying normal physiological signaling.

Spider venom peptides typically work differently. They block or activate ion channels, often at sites distinct from where natural regulators act. They do not replace missing hormones or modulate receptor signaling in the usual sense. Instead, they provide highly selective tools for controlling specific electrical signaling processes.

Feature | Hormone-Based Peptides | Spider Venom Peptides |

|---|---|---|

Primary mechanism | Receptor activation/modulation | Ion channel block/activation |

Natural function | Physiological signaling | Prey capture/defense |

Structural stability | Variable (often low) | Very high (ICK motif) |

Target selectivity | Good | Often exceptional |

Oral availability | Generally no | Generally no |

Development status | Many approved drugs | Early development |

Versus healing and regenerative peptides

Peptides like BPC-157 and TB-500 promote tissue healing and regeneration through growth factor-like mechanisms. They accelerate wound healing, reduce inflammation, and support recovery from injuries. These mechanisms complement rather than compete with spider venom peptide approaches.

In fact, combination strategies might prove synergistic. Spider venom peptides that reduce pain signaling could be paired with healing peptides that address underlying tissue damage. Antimicrobial spider peptides could prevent infection during wound healing supported by regenerative peptides. The specificity of spider venom peptides for neural and inflammatory targets leaves room for complementary agents addressing other aspects of injury and disease.

Safety considerations

Despite their origins in venoms designed to harm, spider venom peptides used in research are generally safe when handled appropriately. The same selectivity that makes them useful, their precise targeting of specific molecular systems, also limits their potential for widespread harm.

Target selectivity and safety

Spider venom peptides typically affect one channel or receptor subtype while sparing others. This means they do not cause the broad systemic effects of whole venoms or non-selective drugs. A peptide that blocks Nav1.7 for pain relief, if sufficiently selective, should not affect cardiac sodium channels (Nav1.5) or muscle sodium channels (Nav1.4).

The peptide GsMTx4, the mechanosensitive channel inhibitor, is explicitly described in the literature as non-toxic to mice at research doses. This seems paradoxical for a venom component, but makes sense given its highly specific mechanism. It does not affect most physiological processes, only those involving the particular channels it targets.

Dose considerations

Like all pharmacologically active substances, spider venom peptides require appropriate dosing. Research uses typically involve nanomolar to micromolar concentrations applied to cells or animal models. These doses are far below what might cause systemic toxicity but sufficient to demonstrate target effects.

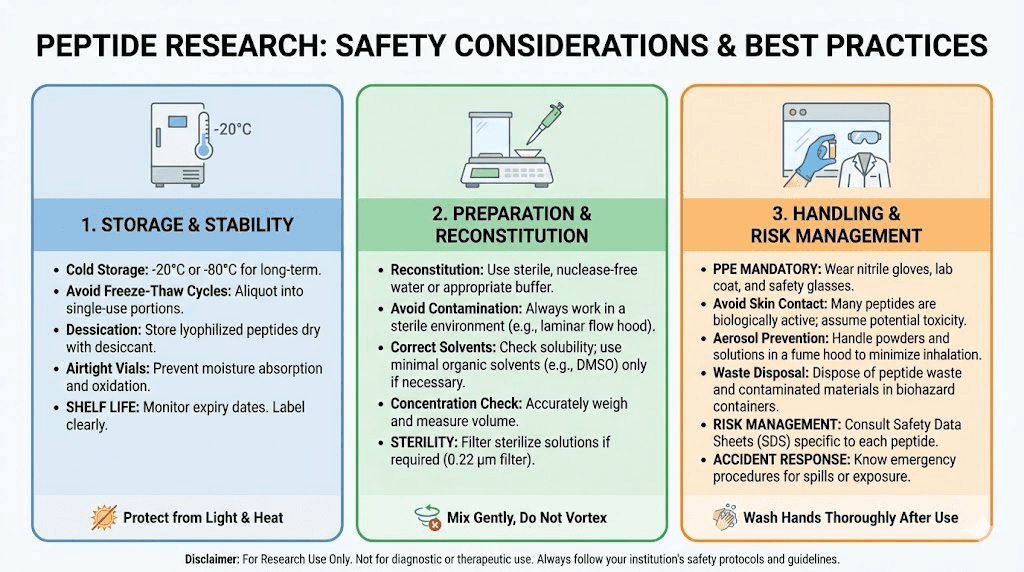

The potency of spider venom peptides, while advantageous for reducing the amount needed for therapeutic effects, means that accurate reconstitution and measurement are essential. Working with these compounds requires standard laboratory safety practices and appropriate training.

Immunogenicity

Foreign peptides can potentially trigger immune responses. For spider venom peptides under therapeutic development, immunogenicity testing is standard. Some peptides may require modification to reduce immune recognition for long-term use. Alternatively, short treatment courses or local administration might limit immune exposure.

Research applications using peptides for brief experiments typically do not encounter significant immunogenicity issues. The concern is more relevant for potential chronic therapeutic use in humans.

Future directions

Spider venom peptide research is poised for significant advances in coming years. Several trends suggest accelerating progress.

Expanded peptide discovery

Modern sequencing technologies enable rapid characterization of venom components from many spider species. Transcriptomics (sequencing the RNA that encodes venom proteins) and proteomics (directly analyzing venom protein composition) have accelerated the pace of new peptide discovery. The estimated 10 million spider venom peptides offer an enormous resource for continued exploration.

Machine learning approaches can predict which peptide sequences might have particular activities based on known structure-function relationships. This allows prioritizing peptides for synthesis and testing, making the discovery process more efficient.

Improved delivery technologies

Advances in drug delivery continue opening new possibilities for peptide therapeutics. Nanoparticle carriers can protect peptides from degradation, enhance tissue penetration, and enable targeted delivery to specific organs or cell types. Nasal delivery can provide brain access for neuroactive peptides. Transdermal patches and implants offer sustained release options.

For spider venom peptides targeting the nervous system, delivery to appropriate sites remains crucial. Technologies that enable brain penetration without invasive procedures would dramatically expand therapeutic possibilities.

Rational peptide engineering

Understanding how spider venom peptides interact with their targets at atomic resolution enables rational engineering of improved variants. Researchers can modify specific amino acids to enhance selectivity, reduce immunogenicity, improve stability, or alter pharmacokinetic properties. These designed variants might outperform natural peptides for specific therapeutic applications.

One study demonstrated this approach by engineering a spider peptide targeting sodium channels. Modifications based on structural understanding enhanced the peptide potency and produced improved anti-nociceptive (pain-reducing) effects in animals. Such rational design approaches will likely produce many optimized spider peptide variants.

Expanded therapeutic applications

As researchers better understand spider venom peptide mechanisms, new therapeutic applications emerge. Current work explores peptides for conditions including autoimmune diseases (via Kv1.3 channel inhibition), cardiac arrhythmias (via mechanosensitive and sodium channel modulation), and neurodegeneration (via various neuroprotective mechanisms).

The diversity of spider venom peptide targets ensures continued discovery of new potential applications. Essentially any condition involving ion channel dysfunction or membrane disruption might be amenable to spider peptide-based approaches.

Frequently asked questions

Are spider venom peptides safe to work with in research?

Spider venom peptides used in research are generally safe when handled with standard laboratory precautions. Their high target selectivity limits potential for broad toxic effects. The peptides are used at nanomolar to micromolar concentrations for their specific activities, far below concentrations that would cause systemic toxicity. As with any pharmacologically active compounds, appropriate training and handling procedures should be followed.

How do spider venom peptides compare to ziconotide for pain treatment?

Ziconotide, derived from cone snail venom, requires intrathecal administration via implanted pump due to poor systemic penetration. Some spider venom peptides show better tissue penetration properties that might allow less invasive delivery. Spider peptides also target different molecular pathways, with some showing efficacy in pain models where ziconotide has limitations. Multiple spider peptides are in development as potential next-generation pain therapeutics targeting chronic pain.

Can spider venom peptides be taken orally?

Like most peptides, spider venom peptides are generally not orally bioavailable because digestive enzymes break them down before absorption. However, the exceptional stability of ICK-motif spider peptides means they resist degradation better than most peptides. Researchers are exploring whether modified versions or protective delivery systems might enable oral administration for specific applications.

What makes spider venom peptides different from synthetic peptides?

Spider venom peptides have been naturally optimized through hundreds of millions of years of evolution for high affinity, selectivity, and stability. They typically contain the ICK structural motif that provides extraordinary resistance to degradation. Synthetic peptides designed from scratch must achieve these properties through deliberate engineering, often requiring extensive optimization. However, once natural spider peptide sequences are identified, they can be produced synthetically for research use.

Which spider venom peptides show the most promise for drug development?

Several peptides are progressing through development. Nav1.7-selective inhibitors for pain treatment have attracted significant investment. The Nav1.1 activator Hm1a for Dravet syndrome epilepsy is advancing toward clinical studies. Antimicrobial peptides like Ltc2a offer potential against drug-resistant infections. ASIC inhibitors show promise for both pain and stroke. The most advanced applications will likely reach clinical trials within the next several years.

Are spider venom peptides being used in cosmetics or skincare?

Some cosmetic products market synthetic peptides inspired by or derived from venoms, often called syn-ake or similar names. These typically target muscle contraction to reduce wrinkles. However, these are generally simplified synthetic analogs rather than actual spider venom peptides. True spider venom peptides remain primarily in the research domain rather than commercial cosmetics, though their skin-related applications continue to be explored.

How are spider venom peptides stored and handled?

Spider venom peptides require storage conditions similar to other research peptides. Lyophilized (freeze-dried) peptides are typically stored at negative 20 degrees Celsius or colder. Reconstituted peptides should be stored frozen in aliquots to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Working solutions may be kept refrigerated for short periods depending on the specific peptide stability. Proper storage procedures maintain peptide activity and research reliability.

In case I do not see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night. May your research stay rigorous, your peptides stay stable, and your discoveries stay transformative. Join us today.