Jan 27, 2026

Of all the questions researchers ask about KPV, one keeps surfacing with increasing urgency. Can this tiny tripeptide actually influence cancer development? The answer is not what you would expect. It is neither a simple yes nor a definitive no. Instead, the research reveals something far more nuanced, something that depends entirely on how cancer develops in the first place.

KPV is a three-amino-acid sequence, just lysine, proline, and valine. That is it. Yet this microscopic fragment of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone has demonstrated remarkable effects in laboratory studies. When inflammation drives cancer formation, KPV appears to interrupt that process. When cancer develops through genetic mutations independent of inflammation, KPV does not seem to help. Understanding this distinction is critical for anyone researching this peptide.

The relationship between chronic inflammation and cancer is well established. Years of inflammatory damage can transform healthy cells into malignant ones. This is especially true in the colon, where conditions like ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease dramatically increase cancer risk. KPV enters this picture as a potent anti-inflammatory agent, one that works through mechanisms most other compounds cannot access. Whether you are trying to understand inflammation peptides or specifically researching cancer prevention pathways, this guide covers what the science actually shows about KPV and malignancy.

SeekPeptides provides detailed research protocols and evidence-based guides for researchers investigating peptide applications. This article examines the complete body of KPV cancer research, from cellular mechanisms to animal studies, without exaggeration or unfounded claims.

What is KPV and where does it come from

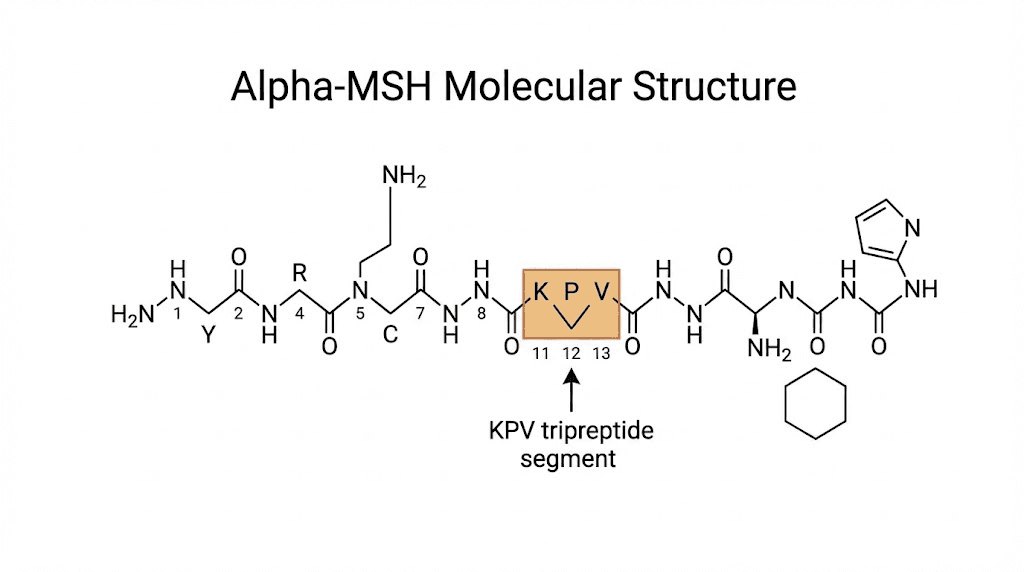

KPV is not a synthetic creation designed in a laboratory. It exists naturally in your body right now. This tripeptide represents the final three amino acids at the C-terminal end of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, commonly abbreviated as alpha-MSH. Your pituitary gland produces alpha-MSH, and when the hormone breaks down through normal metabolic processes, KPV emerges as one of the fragments.

The full alpha-MSH molecule contains thirteen amino acids. Researchers discovered something remarkable when they began dissecting its structure. Most of the anti-inflammatory activity concentrated in those last three amino acids. KPV alone, without the other ten amino acids, demonstrated effects equal to or stronger than the complete hormone. This finding opened new possibilities for therapeutic applications because smaller peptides typically absorb better and cause fewer side effects.

The molecular weight of KPV is approximately 342 daltons. Compare that to full-length alpha-MSH at around 1665 daltons. This size difference matters tremendously for practical applications. Smaller molecules cross biological barriers more easily. They survive digestion better than larger peptides. They can potentially reach target tissues that larger molecules cannot.

How KPV differs from other alpha-MSH fragments

Alpha-MSH breaks down into multiple fragments during metabolism. Not all of them retain biological activity. KPV stands apart because it maintains the core anti-inflammatory signaling capacity of the parent hormone. Other fragments may have different effects or no measurable activity at all.

The significance of position matters here. KPV sits at positions 11, 12, and 13 of the alpha-MSH sequence. Earlier research identified positions 6 through 9 as the melanocortin receptor binding region. That region controls skin pigmentation effects. The C-terminal KPV sequence operates through different pathways entirely, which is why it can exert anti-inflammatory effects without causing the tanning that full alpha-MSH produces.

Some researchers have studied variations of KPV with modified amino acids. These analogs attempt to improve stability or potency. However, the natural KPV sequence remains the most extensively studied form, and the cancer research discussed in this article uses this original tripeptide structure.

The inflammation to cancer connection

Before understanding how KPV might influence cancer, you need to understand how inflammation causes cancer in the first place. This is not speculation. Decades of research have established that chronic inflammation directly promotes malignant transformation in certain tissues.

The colon provides the clearest example. People with inflammatory bowel disease, which includes both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, face significantly elevated cancer risk. The longer inflammation persists, the higher the risk climbs. After a decade of active ulcerative colitis, some estimates suggest cancer risk increases by 2 percent per year. That cumulative risk becomes substantial over a lifetime.

Inflammation promotes cancer through multiple mechanisms. Immune cells release reactive oxygen species that damage DNA. Inflammatory signaling pathways accelerate cell division. The constant cycle of tissue damage and repair creates opportunities for mutations to accumulate. Growth factors released during inflammation can push precancerous cells toward full malignancy.

NF-kB and the inflammatory cascade

Nuclear factor kappa B, abbreviated NF-kB, sits at the center of inflammatory signaling. This transcription factor controls the expression of hundreds of genes involved in immune responses, cell survival, and proliferation. When NF-kB activates inappropriately or persistently, it drives chronic inflammation.

Cancer researchers have identified NF-kB as a critical link between inflammation and malignancy. Activated NF-kB promotes tumor cell survival by blocking apoptosis, the natural cell death process that normally eliminates damaged cells. It stimulates angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels that tumors need to grow. It increases invasion and metastasis by upregulating enzymes that break down tissue barriers.

KPV works in part by blocking NF-kB activation. Laboratory studies show that KPV prevents the nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit of NF-kB. Without this translocation, NF-kB cannot activate its target genes. This represents one of the primary mechanisms through which KPV exerts anti-inflammatory effects. It also represents a potential point of intervention in the inflammation to cancer progression.

The safety profile of peptides generally compares favorably to traditional anti-inflammatory drugs. This matters because preventing cancer requires long-term intervention, and any preventive agent must be tolerable over extended periods.

PepT1 and targeted delivery

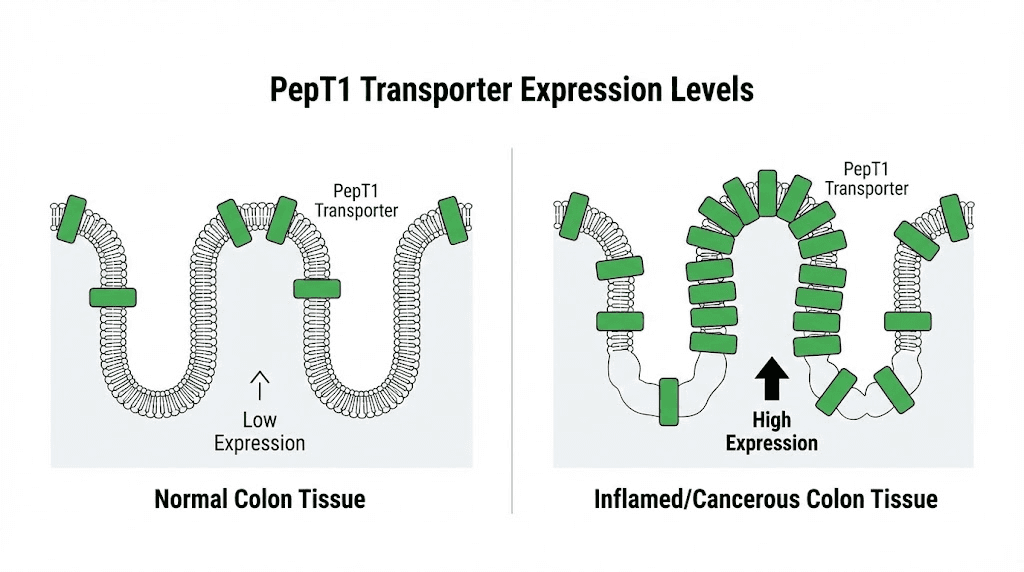

One of the most fascinating aspects of KPV research involves its transport mechanism. PepT1, also called peptide transporter 1, is a protein that moves di- and tripeptides across cell membranes. Under normal conditions, PepT1 expression in the colon is low. But during inflammation, PepT1 expression increases dramatically.

This upregulation creates a therapeutic window. Inflamed intestinal tissue expresses more PepT1, which means it takes up more KPV. Healthy tissue with low PepT1 expression absorbs less. The result is preferential delivery of KPV to the areas that need it most. This targeting mechanism does not exist for most anti-inflammatory drugs.

Research published in Gastroenterology demonstrated that PepT1 actively transports KPV into intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells. Once inside, KPV accumulates in the cytosol where it can inhibit inflammatory signaling pathways. This mechanism explains why oral peptide delivery works for KPV when many other peptides require injection.

KPV in colitis-associated cancer models

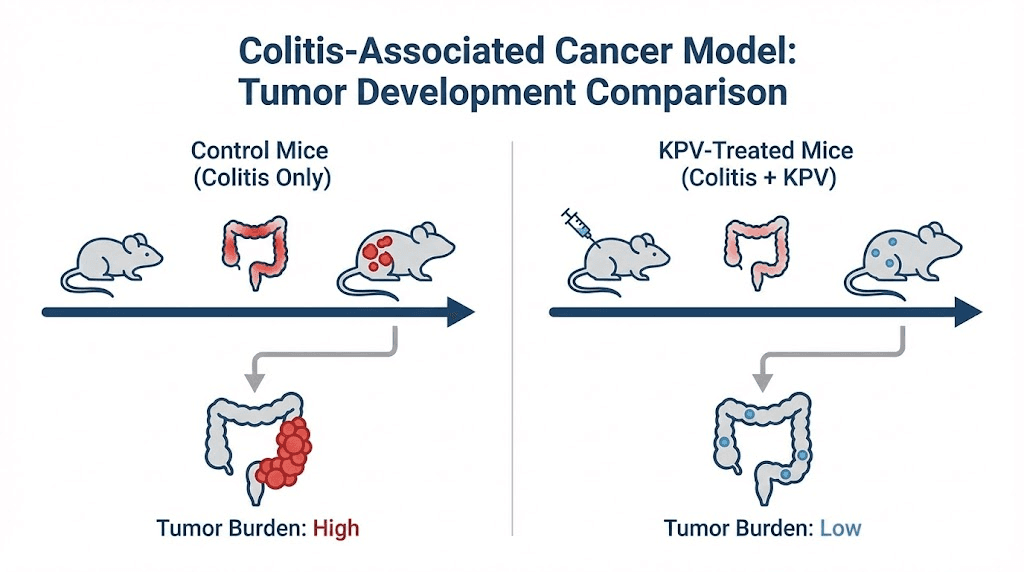

The strongest evidence for KPV influence on cancer comes from colitis-associated cancer models in mice. These experimental systems mimic the inflammation to cancer progression seen in humans with inflammatory bowel disease. Researchers use chemical agents to induce colitis, then observe tumor development over subsequent weeks.

The most commonly used model combines azoxymethane (AOM) with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS). AOM is a carcinogen that initiates DNA damage. DSS induces colitis by disrupting the intestinal barrier. Together, they reliably produce colon tumors in mice within a predictable timeframe. This model has been validated against human colitis-associated cancer and shares many molecular features with the human disease.

What the mouse studies showed

A pivotal study published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology examined KPV effects in the AOM/DSS model. Researchers administered KPV orally during the inflammation phase and continued through tumor development. The results were striking.

KPV-treated mice showed significantly fewer tumors than untreated mice. Tumor incidence dropped substantially in the treatment group. Beyond just tumor number, the tumors that did develop were smaller and less advanced. Histological examination revealed reduced cellular proliferation markers in KPV-treated animals.

The anti-inflammatory effects were equally impressive. KPV-treated mice had lower levels of inflammatory cytokines in their colonic tissue. Fewer aberrant crypt foci, the precursor lesions that can develop into tumors, appeared in treated animals. Cellular infiltration, a marker of active inflammation, decreased with KPV administration.

Perhaps most importantly, these effects depended on PepT1. When researchers repeated the experiment in PepT1 knockout mice, KPV provided no protection against tumor development. This confirmed that PepT1-mediated transport is essential for KPV activity in this context. The peptide needs to enter cells through this transporter to exert its effects.

Mechanisms of tumor suppression

The research identified several mechanisms through which KPV reduced tumor development in these models. First, KPV decreased the activation of NF-kB in colonic tissue. Lower NF-kB activity meant reduced expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-survival genes that tumors exploit for growth.

Second, KPV reduced proliferation of colonic epithelial cells. Using Ki-67 staining, a marker of actively dividing cells, researchers found fewer proliferating cells in KPV-treated animals. Cancer requires unchecked proliferation, and any reduction in cell division rates slows tumor growth.

Third, KPV preserved intestinal barrier function. The gut barrier normally prevents bacteria and their products from entering the bloodstream. Barrier dysfunction, called leaky gut, drives inflammation through bacterial translocation. By maintaining barrier integrity, KPV interrupted a key driver of colonic inflammation.

Fourth, KPV modulated immune cell behavior. Macrophages and T cells in KPV-treated mice showed reduced inflammatory activation. These immune cells can either promote or suppress tumor development depending on their activation state. Shifting them toward a less inflammatory phenotype creates an environment less hospitable to tumor growth.

The tissue repair properties of certain peptides may also contribute to cancer prevention. Healthy tissue that repairs efficiently has less opportunity for malignant transformation than tissue stuck in cycles of damage and incomplete healing.

Limitations found in genetic cancer models

Not all cancer develops from inflammation. Some cancers arise primarily from genetic mutations that accumulate over time. To test whether KPV could influence this type of cancer, researchers used a different mouse model called APCMin/+.

These mice carry a mutation in the APC tumor suppressor gene, the same gene mutated in familial adenomatous polyposis in humans. APCMin/+ mice spontaneously develop intestinal adenomas without requiring any external carcinogen or inflammatory insult. The tumors arise from genetic predisposition rather than environmental inflammation.

Results in the APCMin/+ model

Researchers administered KPV to APCMin/+ mice for 13 weeks and then assessed tumor development. The findings differed dramatically from the colitis-associated cancer model. KPV did not reduce tumor number in either the small intestine or the colon. The genetic cancer proceeded regardless of KPV treatment.

Interestingly, KPV still demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects in these mice. Lipocalin-2, a marker of intestinal inflammation, decreased in KPV-treated animals. The peptide maintained its core anti-inflammatory activity. But that anti-inflammatory effect did not translate into tumor prevention when cancer arose from genetic rather than inflammatory causes.

This finding has important implications for understanding KPV potential applications. The peptide appears to work by interrupting the inflammation to cancer pathway specifically. When inflammation does not drive cancer development, KPV does not prevent it. This is not a failure of KPV. It is a clarification of its mechanism.

What this means for human applications

Human colon cancer develops through multiple pathways. Some cases clearly arise from chronic inflammatory conditions. Others develop in people with no history of inflammatory bowel disease through accumulation of genetic mutations. The APCMin/+ results suggest KPV would only benefit the first category.

For individuals with ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease who face elevated cancer risk due to ongoing inflammation, KPV represents a mechanistically rational intervention. The research provides biological plausibility for its potential preventive effect in this specific population.

For individuals without inflammatory bowel disease, the evidence does not support KPV as a cancer preventive. Their cancer risk derives from different factors that KPV does not address. Understanding this distinction prevents both false hope and inappropriate dismissal of the research.

The broader field of peptide research and studies continues to identify compounds with specific mechanisms suited to particular conditions. KPV exemplifies this principle of targeted application based on underlying biology.

PepT1 expression in human colorectal cancer

The mouse studies raised an obvious question. Does PepT1 expression increase in human colorectal tumors as it does in inflamed mouse colons? If PepT1 were not upregulated in human disease, the mouse findings might not translate to clinical relevance.

Researchers analyzed human colonic biopsy specimens from patients with colorectal cancer. The results confirmed elevated PepT1 expression in tumor tissue compared to adjacent normal tissue. This finding has two implications. First, it validates the mouse model as relevant to human disease. Second, it suggests that human colorectal tumors might similarly take up KPV through PepT1.

Implications for targeted therapy

The PepT1 expression pattern creates a potential opportunity for targeted delivery. Drugs or peptides transported by PepT1 could achieve higher concentrations in tumor tissue than in healthy tissue. This differential uptake could improve therapeutic ratios by concentrating active compounds where they are needed while minimizing exposure to normal cells.

Several research groups have begun exploring PepT1 as a drug delivery target. KPV-loaded nanoparticles have been developed to enhance stability and targeting. These formulations show promise in preclinical testing, with improved delivery to inflamed intestinal tissue compared to free KPV.

One study used hyaluronic acid-functionalized nanoparticles to deliver KPV. The nanoparticles measured approximately 272 nanometers in diameter with a slightly negative surface charge. They successfully delivered KPV to colonic epithelial cells and macrophages. In ulcerative colitis models, these KPV-loaded nanoparticles accelerated mucosal healing and reduced inflammation.

The development of improved delivery systems could make KPV more practical for clinical applications. Current research peptides often have bioavailability limitations that advanced formulations might overcome.

Molecular mechanisms of KPV anti-cancer effects

Understanding exactly how KPV exerts its effects requires examining multiple molecular pathways. The peptide does not work through a single mechanism. Instead, it influences several interconnected signaling cascades that together reduce inflammation and potentially prevent cancer development.

NF-kB pathway inhibition

The nuclear factor kappa B pathway represents the primary target of KPV activity. When inflammatory signals activate cells, a series of molecular events normally lead to NF-kB entering the nucleus and activating gene transcription. KPV interrupts this process at a specific step.

Normally, importin alpha-3 binds to the p65 subunit of NF-kB and transports it into the nucleus. KPV competes for this binding. When KPV occupies the importin alpha-3 binding site, p65 cannot be transported. It remains in the cytoplasm where it cannot activate inflammatory genes.

This mechanism explains why KPV reduces expression of numerous inflammatory mediators simultaneously. NF-kB controls the transcription of interleukins, tumor necrosis factor alpha, cyclooxygenase-2, and many other inflammatory molecules. By blocking NF-kB activation, KPV suppresses all these downstream targets at once.

The fundamental mechanisms of how peptides work often involve modulating signaling pathways rather than blocking individual receptors. This pathway-level intervention can produce broader effects than single-target drugs.

MAPK pathway modulation

The mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, abbreviated MAPK, provides another route through which KPV reduces inflammation. This pathway includes several related kinases, including ERK, JNK, and p38, that transmit signals from the cell surface to the nucleus.

Research shows KPV attenuates activation of ERK and p38 MAPK in intestinal epithelial cells. These kinases normally become phosphorylated and activated during inflammatory stimulation. With KPV present, phosphorylation decreases, and downstream signaling diminishes.

The MAPK pathway contributes to inflammation through mechanisms distinct from NF-kB. It controls cell stress responses, cytokine production, and proliferation. By reducing MAPK activation alongside NF-kB inhibition, KPV achieves more comprehensive anti-inflammatory coverage.

Cytokine effects

The end result of signaling pathway inhibition is reduced cytokine production. Laboratory studies consistently show that KPV decreases pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion from multiple cell types. Tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and other inflammatory mediators all decrease in KPV-treated cells.

Importantly, KPV appears to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines without substantially increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines. This suggests it works primarily by suppressing inflammatory activation rather than by shifting the balance toward anti-inflammatory mediators. The practical implication is that KPV should not cause the immunosuppression associated with some anti-inflammatory treatments.

Cytokine reduction matters for cancer prevention because these molecules create the inflammatory microenvironment that promotes tumor development. Tumors exploit inflammatory cytokines for growth signals, blood vessel formation, and immune evasion. Reducing the cytokine milieu removes support that nascent tumors depend on.

Comparing KPV to other anti-inflammatory approaches for cancer prevention

KPV is not the only compound studied for inflammation-associated cancer prevention. Several other approaches have shown activity in similar models. Understanding how KPV compares to these alternatives helps contextualize its potential role.

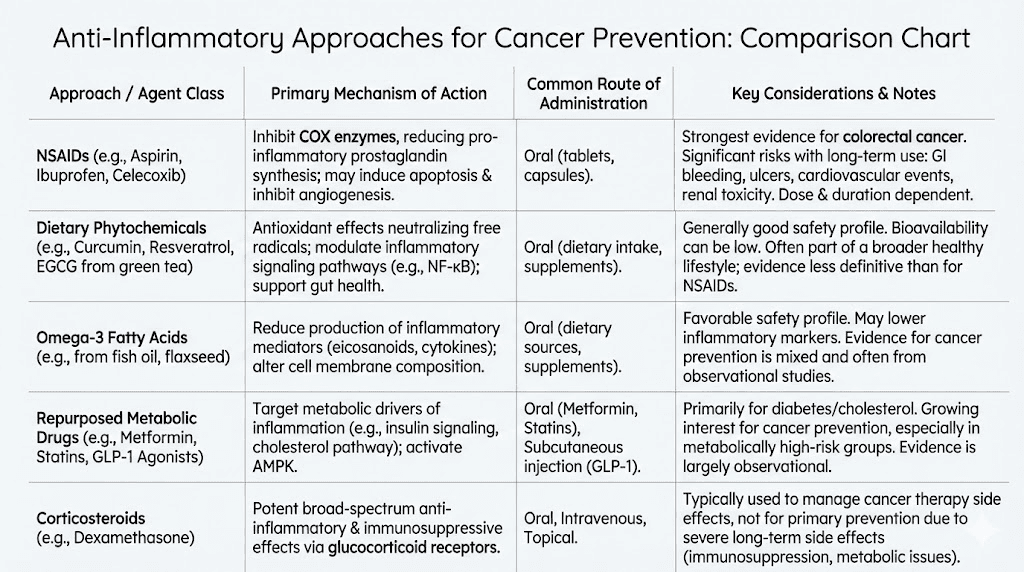

NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have a long history in colorectal cancer prevention research. Aspirin in particular has shown consistent ability to reduce colorectal cancer risk in observational studies and some clinical trials. The mechanism involves inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes that produce inflammatory prostaglandins.

However, NSAIDs carry significant risks with long-term use. Gastrointestinal bleeding, cardiovascular events, and kidney damage limit their suitability for chemoprevention in many individuals. The risk-benefit calculation becomes challenging when considering years or decades of preventive use.

KPV offers a potentially different risk profile. As a naturally occurring peptide fragment, it may avoid some of the off-target effects that plague synthetic drugs. Early research has not identified significant safety concerns, though human studies remain limited. The safety considerations for peptide use generally differ from those of small molecule drugs.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids powerfully suppress inflammation and are commonly used to treat inflammatory bowel disease flares. However, they cause serious adverse effects with long-term use, including osteoporosis, diabetes, immunosuppression, and adrenal dysfunction. No one advocates corticosteroids for cancer chemoprevention.

KPV achieves anti-inflammatory effects without the systemic hormonal disruption that corticosteroids cause. It does not appear to affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis or cause metabolic derangements. This targeted mechanism could enable long-term use that corticosteroids do not permit.

Biologics

Biologic drugs targeting specific cytokines have transformed inflammatory bowel disease treatment. Anti-TNF antibodies like infliximab, anti-integrin antibodies like vedolizumab, and others effectively control inflammation in many patients.

These drugs are expensive, require injection or infusion, and carry risks including serious infections and potential malignancy. Their role in cancer prevention is unclear. Controlling inflammation should theoretically reduce cancer risk, but long-term data are still accumulating.

KPV could potentially offer a simpler, less expensive alternative for some applications. Oral administration, lower molecular weight, and apparently favorable safety suggest possible advantages. However, direct comparisons in clinical settings have not been conducted.

Administration routes and considerations

Research has explored multiple routes for KPV administration. Each has advantages and limitations that affect suitability for different applications. Understanding these options helps researchers design appropriate protocols.

Oral administration

The ability to take KPV orally distinguishes it from many therapeutic peptides that require injection. Most peptides degrade in the gastrointestinal tract before they can be absorbed. KPV survives digestion well enough to reach the intestinal epithelium and enter cells through PepT1.

For gut-related conditions including inflammatory bowel disease and potentially colitis-associated cancer prevention, oral administration makes particular sense. The peptide contacts the inflamed tissue directly as it passes through. Local concentrations can be high even if systemic absorption is limited.

Research protocols typically use doses in the range of 500 to 1500 micrograms daily for oral administration. Some experimental protocols report higher doses up to 10 to 20 milligrams. The optimal dose has not been established through rigorous clinical testing.

The KPV peptide dosage guide provides more detailed information on administration protocols used in various research settings.

Subcutaneous injection

Subcutaneous injection bypasses the digestive system and provides more predictable systemic absorption. Research protocols using injection typically employ lower doses than oral protocols, often in the range of 200 to 500 micrograms daily.

For systemic inflammatory conditions or applications where gut exposure is not specifically desired, injection may be preferred. It ensures the peptide enters circulation without uncertainty about oral bioavailability.

Injection does require proper technique and sterile supplies. The peptide injections guide covers practical considerations for subcutaneous administration of research peptides.

Topical application

KPV has also been studied for topical use in skin inflammation. Creams containing KPV at concentrations around 0.005 to 1 percent have been applied directly to affected areas. This route would not be relevant for colon cancer prevention but demonstrates the peptide versatility.

The skin contains melanocortin receptors that can respond to alpha-MSH-derived peptides. Topical KPV may reduce local inflammation in conditions like dermatitis or wound healing applications.

Nanoparticle formulations

Advanced drug delivery research has developed nanoparticle formulations to improve KPV delivery. These include hyaluronic acid-coated nanoparticles that target inflamed tissue and protect the peptide from degradation.

In animal models of ulcerative colitis, nanoparticle-delivered KPV showed effectiveness at doses 12,000-fold lower than free KPV in solution. This dramatic dose reduction results from improved targeting and protection from degradation.

Nanoparticle formulations remain experimental and are not available for general research use. They represent a potential future direction for KPV development if clinical interest progresses.

Current regulatory status and limitations

KPV has not been approved by the FDA or any regulatory agency for therapeutic use. It is classified as a research chemical without approved medical indications. This status creates both limitations and considerations for researchers.

FDA position

The FDA has included KPV in statements about bulk drug substances that may pose safety risks. Specifically, the agency noted that it has not identified human exposure data for drug products containing KPV and lacks important safety information. This does not mean KPV is known to be dangerous. It means adequate safety studies have not been submitted to the agency.

Without FDA approval, KPV cannot be marketed as a treatment or supplement in the United States. Compounding pharmacies have limited ability to prepare KPV products. The practical result is that access is primarily through research chemical suppliers.

Research chemical considerations

KPV obtained from research chemical suppliers is intended for laboratory investigation, not human use. Quality can vary between suppliers. Purity testing and certificate of analysis documentation become important when selecting sources.

The best peptide vendors provide third-party testing documentation. Researchers should verify purity and identity before using any peptide in experiments.

Clinical trial status

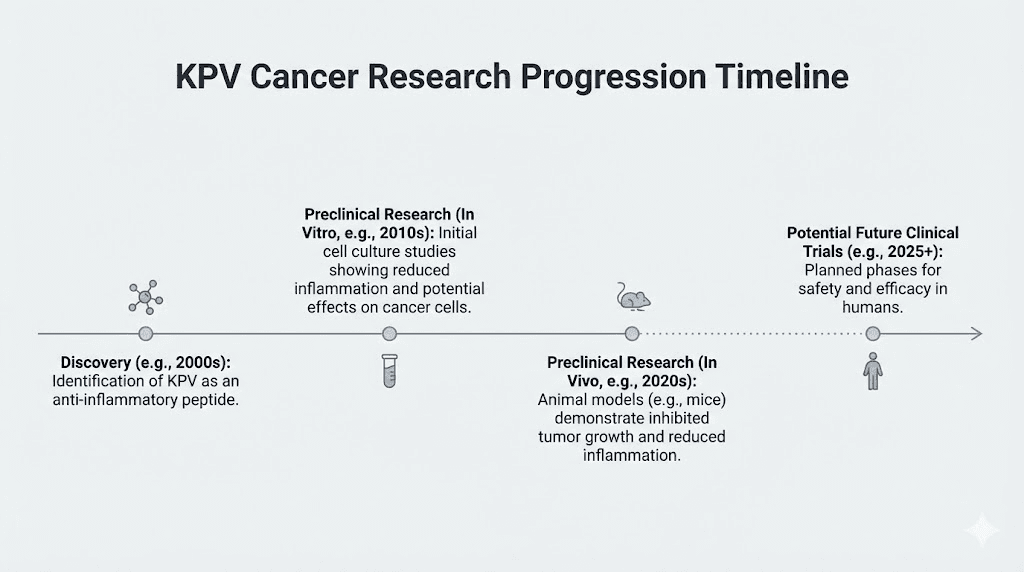

As of the current research literature, no clinical trials have evaluated KPV specifically for cancer prevention in humans. The evidence base remains preclinical, consisting of cell culture and animal model studies. This represents a significant limitation in translating laboratory findings to clinical practice.

Clinical trials would be needed to establish safety in humans, determine optimal dosing, identify which patient populations might benefit, and confirm efficacy. Until such trials are conducted, KPV cancer prevention potential remains theoretical.

The broader context of peptides and cancer

KPV is one example of peptides being investigated for potential cancer applications. The broader field of anticancer peptides has expanded substantially in recent years. Understanding this context helps place KPV research within a larger scientific landscape.

Anticancer peptide mechanisms

Peptides can influence cancer through multiple mechanisms beyond inflammation modulation. Some peptides directly kill cancer cells by disrupting their membranes. Others interfere with signaling pathways that cancer cells depend on. Still others modulate immune responses to enhance anti-tumor immunity.

KPV works primarily through the inflammation pathway. This positions it more as a preventive agent for inflammation-driven cancers than as a treatment for established malignancies. Other peptides may be more suitable for therapeutic applications against existing tumors.

The complete peptide list includes compounds studied for various applications including cancer research. Each has distinct mechanisms and potential uses.

Advantages of peptide approaches

Peptides offer several theoretical advantages over small molecule drugs for cancer applications. They can achieve high target specificity, reducing off-target effects. They typically undergo predictable metabolism without generating toxic metabolites. They can be designed or discovered with particular mechanisms in mind.

The disadvantages include potential instability, limited oral bioavailability for most peptides, possible immunogenicity, and often higher production costs than small molecules. These factors affect practical development and clinical translation.

Future directions

Research into KPV and related peptides continues. Several directions seem promising. First, better delivery systems could improve efficacy and reduce required doses. Second, combination approaches with other anti-inflammatory or anticancer agents might produce synergistic effects. Third, biomarker development could identify individuals most likely to benefit from KPV intervention.

The field of longevity peptides overlaps with cancer prevention research since avoiding malignancy is essential for extended healthspan. Peptides that reduce chronic inflammation could theoretically contribute to both longevity and cancer prevention goals.

Practical considerations for researchers

Researchers investigating KPV for cancer-related studies face several practical considerations. Proper experimental design requires attention to compound handling, dosing, and appropriate controls.

Peptide stability

KPV is relatively stable compared to larger peptides, but still requires proper storage. Lyophilized powder should be stored at -20C or colder. Reconstituted solutions have limited stability and should be refrigerated and used within weeks. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided.

The peptide storage guide provides detailed information on maintaining peptide integrity during research.

Reconstitution

KPV dissolves readily in sterile water or bacteriostatic water. Concentrations should be calculated carefully to allow accurate dosing. The how to reconstitute peptides guide covers proper technique for preparing peptide solutions.

Experimental controls

Cancer prevention studies require appropriate controls to interpret results. Vehicle-treated groups establish baseline tumor development. Positive controls using known anti-inflammatory agents help contextualize KPV effects. Time course studies reveal when intervention is most effective.

The PepT1 knockout mice used in some studies provide an excellent negative control for mechanism validation. If KPV effects disappear without PepT1, transport through this pathway is confirmed as necessary.

Model selection

As discussed, different cancer models yield different results with KPV. The AOM/DSS inflammation-driven model shows KPV effects. The APCMin/+ genetic model does not. Researchers must select models appropriate for their specific questions.

For cancer prevention studies, the AOM/DSS model or similar inflammation-associated protocols are most relevant. For studies asking whether KPV can treat established genetic cancers, different approaches would be needed.

KPV in combination protocols

Some researchers have explored KPV in combination with other peptides or compounds. Combination approaches may provide enhanced effects compared to single agents. Several combinations appear in the research literature.

KPV with BPC-157

BPC-157, another peptide with tissue-protective properties, has been combined with KPV in some protocols. The rationale involves complementary mechanisms. BPC-157 promotes wound healing and tissue repair through growth factor pathways. KPV reduces inflammation through NF-kB and MAPK inhibition.

Together, they might provide both tissue protection and anti-inflammatory effects. The BPC-157 and TB-500 stacking guide discusses combination approaches with healing peptides.

For gut inflammation specifically, combining KPV and BPC-157 addresses multiple pathological processes simultaneously. Clinical data on this combination does not exist, but the mechanistic rationale appears sound.

KPV in gut health protocols

Researchers interested in peptides for gut health often include KPV as a component of comprehensive protocols. The peptide anti-inflammatory properties complement other interventions targeting the intestinal barrier, microbiome, or immune function.

Protocol design typically involves sequential or concurrent administration of multiple peptides. The peptide stacks guide provides frameworks for combining peptides based on research goals.

Timing considerations

The KPV peptide morning or night article addresses timing questions that arise in protocol design. For cancer prevention applications, consistent daily dosing likely matters more than specific timing, but individual protocols may vary.

What the evidence does and does not support

After reviewing the complete body of KPV cancer research, we can draw several evidence-based conclusions. These should guide both expectations and further investigation.

What the evidence supports

The evidence clearly supports that KPV exerts anti-inflammatory effects through NF-kB and MAPK pathway inhibition. This has been demonstrated in multiple cell types and confirmed in animal models. The mechanism is well characterized at the molecular level.

The evidence supports that KPV reduces tumor development in colitis-associated cancer models where inflammation drives carcinogenesis. Multiple independent studies show this effect. The finding is biologically plausible given the established link between chronic inflammation and cancer.

The evidence supports that KPV effects in these models depend on PepT1 transport. Knockout experiments confirm this mechanism. The upregulation of PepT1 in human colorectal tumors provides translational relevance.

What the evidence does not support

The evidence does not support that KPV prevents or treats cancers arising from genetic mutations independent of inflammation. The APCMin/+ studies explicitly showed no effect in this context. Extrapolating from colitis-associated cancer to other cancer types is not justified.

The evidence does not support any cancer-related effects in humans. All data comes from cell culture and animal studies. Human clinical trials have not been conducted. The translation from mice to humans often reveals important differences.

The evidence does not support using KPV as a cancer treatment for established tumors. The studies examined prevention during tumor initiation and early development. Effects on advanced malignancies have not been adequately studied.

Appropriate interpretation

KPV represents a promising research compound for understanding the relationship between inflammation and cancer. It provides a tool for investigating how interrupting inflammatory pathways affects tumor development. Its potential clinical applications remain speculative pending human studies.

For individuals with inflammatory bowel disease seeking to reduce their cancer risk, KPV represents one of many research areas being explored. It is not an established treatment. Conventional medical care remains the standard approach for cancer prevention in this population.

SeekPeptides provides research-focused information to help investigators understand peptide mechanisms and design appropriate studies. The platform does not recommend peptides for treating or preventing cancer outside of proper clinical research settings.

Frequently asked questions

Does KPV directly kill cancer cells?

The research does not suggest that KPV directly kills cancer cells through cytotoxic mechanisms. Unlike some anticancer peptides that disrupt tumor cell membranes or induce apoptosis, KPV works primarily by reducing inflammation and creating an environment less favorable for tumor development. It appears to work preventively rather than therapeutically against established cancers.

Can KPV be used alongside conventional cancer treatments?

No clinical data exists on combining KPV with chemotherapy, radiation, or other cancer treatments. Such combinations have not been studied in humans. Anyone receiving cancer treatment should consult their oncologist before considering any additional compounds. Interactions cannot be ruled out without proper investigation.

How does KPV compare to aspirin for cancer prevention?

Aspirin has far more human data supporting its potential role in colorectal cancer prevention. Multiple observational studies and some clinical trials support aspirin effects. KPV has only preclinical data. However, aspirin carries risks of bleeding and cardiovascular effects that KPV may not share. Direct comparison is not possible without human KPV trials.

Would KPV help someone with a family history of colon cancer?

Family history of colon cancer often reflects genetic predisposition rather than inflammatory causes. The APCMin/+ mouse studies suggest KPV does not prevent genetically driven tumors. For individuals with hereditary cancer syndromes, conventional surveillance and prevention strategies remain the standard approach. KPV has not been validated for this population.

How long would someone need to take KPV for cancer prevention?

This question cannot be answered with current evidence. Cancer prevention studies in humans would need to span years or decades to demonstrate meaningful endpoints. No such studies have been conducted with KPV. Duration of use in animal studies ranges from weeks to months, but these timescales do not translate directly to human lifespans.

Are there any known safety concerns with long-term KPV use?

Long-term safety data does not exist for KPV. The FDA has noted the absence of human exposure data as a gap in the safety profile. Short-term animal studies have not identified serious toxicity, but long-term effects remain unknown. Any compound used for cancer prevention would need extensive safety evaluation given the extended exposure involved.

Does KPV work for all types of inflammation-related cancers?

The research has focused primarily on colitis-associated colon cancer. Other inflammation-associated cancers such as hepatocellular carcinoma arising from hepatitis or esophageal cancer from Barrett esophagus have not been specifically studied with KPV. While the mechanisms might theoretically apply, direct evidence is lacking for cancers outside the colon.

External resources

PMC - Critical Role of PepT1 in Colitis-Associated Cancer and KPV Benefits

Gastroenterology - PepT1-Mediated KPV Uptake Reduces Intestinal Inflammation

For researchers serious about understanding peptide mechanisms and their potential applications, SeekPeptides provides comprehensive protocols, evidence-based guides, and a community of researchers exploring these questions together.

In case I do not see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night. May your research stay rigorous, your inflammation stay controlled, and your curiosity stay unquenchable.