Jan 19, 2026

You just got your lab results back. The C-peptide number stares at you from the page, and you have no idea what it means. Is 1.2 ng/mL good? Bad? Somewhere in between? The reference range listed on the report tells you almost nothing about what that number actually means for your health, your metabolic function, or whether you should be concerned.

This is the frustration millions of people face every year. They order tests. They get numbers. And they leave more confused than when they started.

Here is what nobody tells you about C-peptide testing. The normal range is just the beginning. Your result needs context, timing considerations, and an understanding of what your pancreas is actually doing when it produces insulin. Without that context, a C-peptide level is just another number on a piece of paper, disconnected from the metabolic reality it represents.

This guide breaks down everything you need to know about C-peptide levels. We cover the actual normal ranges, what high and low results mean, how doctors use this test to diagnose different conditions, and the factors that can throw off your results entirely. Whether you are trying to understand what peptides are in general or specifically want to decode your C-peptide results, this comprehensive resource has you covered.

SeekPeptides provides evidence-based guides on peptide science, including the biochemistry behind insulin production and the peptides that influence hormonal function, metabolic health, and digestive wellness.

What is C-peptide and why does it matter

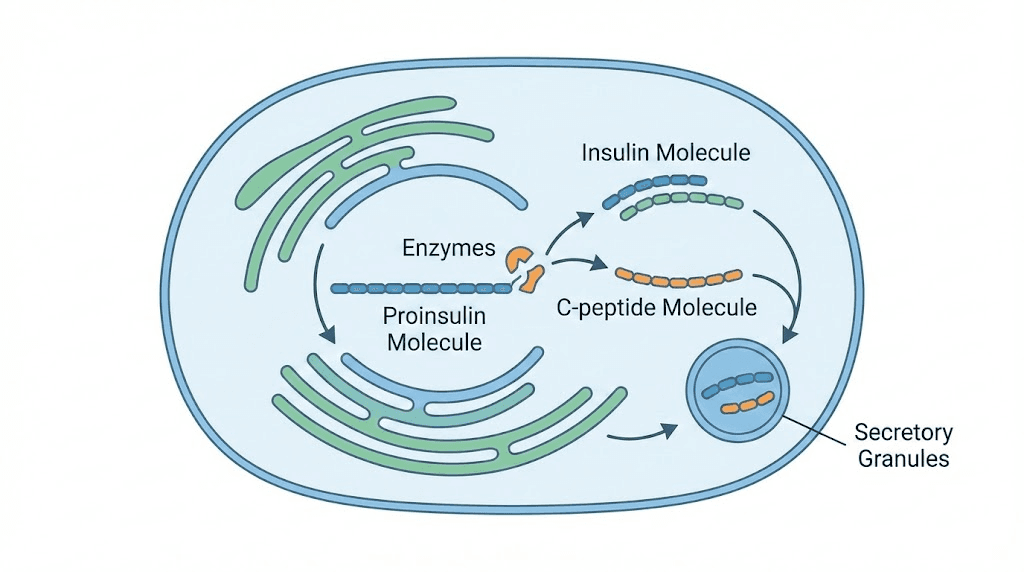

C-peptide stands for connecting peptide. It is a 31-amino acid polypeptide that your pancreas produces when making insulin. The story starts with proinsulin, a larger molecule that contains three parts: the A chain and B chain of insulin, connected by C-peptide in the middle.

When your beta cells need to release insulin, they cleave proinsulin. The result is active insulin plus C-peptide, released into your bloodstream in equal amounts at exactly the same time.

This matters for testing.

Insulin gets metabolized rapidly. Half of it disappears from your blood in just 3 to 5 minutes, and your liver clears about 50% of all insulin secreted before it even reaches the peripheral circulation. C-peptide behaves differently. It has a half-life of 20 to 30 minutes and experiences negligible hepatic clearance, meaning what your pancreas releases is what shows up in your blood.

For researchers studying how peptides function in the body, C-peptide provides a window into endogenous insulin production that direct insulin measurement cannot match. This makes C-peptide the gold standard marker for assessing how much insulin your body naturally produces, regardless of whether you take insulin injections or other peptide-based therapies.

The relationship between C-peptide and insulin

Your pancreas produces C-peptide and insulin in a 1:1 ratio. Always. This equimolar secretion means that measuring C-peptide tells you exactly how much insulin your pancreas made, without the complications that come with measuring insulin directly.

Why not just measure insulin? Several reasons make this problematic. First, exogenous insulin from injections contains no C-peptide, so people taking insulin medications would show high insulin levels that do not reflect their natural production. Second, insulin measurement fluctuates wildly due to rapid clearance and variable hepatic extraction. Third, some insulin assays cross-react with proinsulin or insulin antibodies, creating false readings.

C-peptide avoids all these issues. It provides a stable, reliable, and specific measurement of beta cell function that works even in people receiving weight loss peptide treatments, muscle-building protocols, or other interventions that might affect insulin dynamics.

Where C-peptide is cleared from the body

Understanding C-peptide clearance matters for accurate interpretation. Your kidneys handle approximately 70% of C-peptide removal from your bloodstream.

They filter it at the glomerulus, and most gets degraded in the kidney rather than excreted in urine.

Only about 14% of filtered C-peptide actually appears in your urine.

This renal clearance has important implications. If your kidney function is impaired, C-peptide levels can rise 2 to 5 times higher than normal, not because your pancreas is making more insulin, but because your kidneys cannot clear the C-peptide efficiently. Doctors must interpret C-peptide results alongside kidney function tests like creatinine and eGFR to avoid misdiagnosis.

The kidney connection also explains why researchers studying peptides for gut health or other therapeutic applications need to account for renal function when evaluating metabolic markers. A high C-peptide in someone with chronic kidney disease means something entirely different than the same number in someone with healthy kidneys.

Normal C-peptide levels explained

The reference ranges for C-peptide depend on when the sample was collected and which units your lab uses. Most laboratories in the United States report results in ng/mL, while international labs often use nmol/L. Converting between these units requires dividing ng/mL by 0.33 to get nmol/L.

Fasting C-peptide normal range

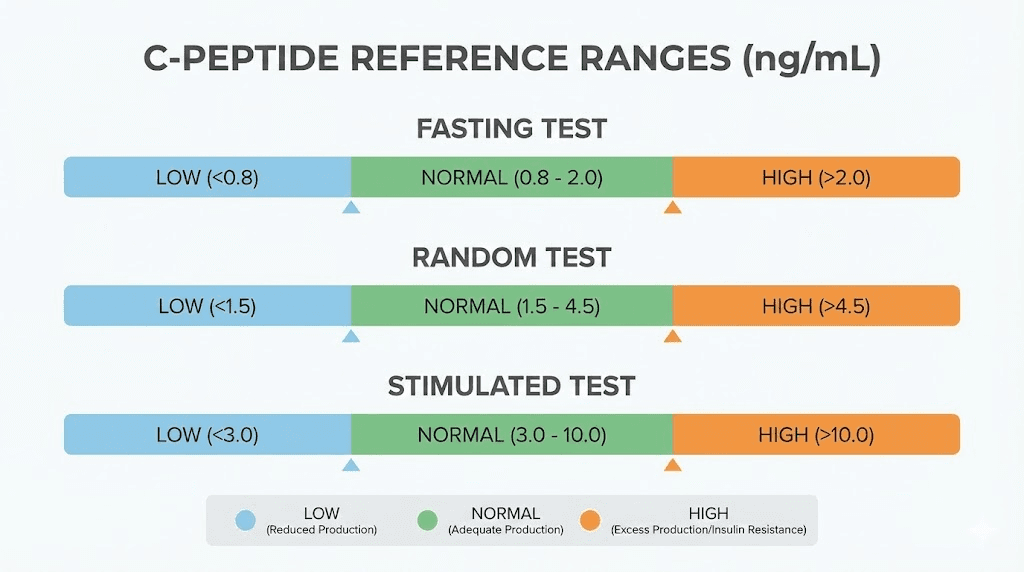

For blood samples collected after an overnight fast of 8 to 12 hours, normal C-peptide levels typically fall between:

0.5 to 2.0 ng/mL (or 0.17 to 0.66 nmol/L)

Some laboratories use slightly different ranges. You might see 0.3 to 2.4 ng/mL reported as normal. The variation comes from different assay methods, population calibrations, and laboratory-specific standardization procedures.

What does fasting C-peptide tell you? When you have not eaten for 8 or more hours, your blood glucose should be relatively low, and your pancreas should be producing only baseline amounts of insulin to maintain that glucose level. A fasting C-peptide within the normal range suggests your beta cells are functioning appropriately at rest.

Researchers working with reconstituted peptides and other compounds that might affect insulin sensitivity often use fasting C-peptide as a baseline measurement to track metabolic changes over time.

Random C-peptide normal range

Random or non-fasting C-peptide samples can be collected at any time without regard to recent food intake. The normal range for random samples is broader:

0.5 to 3.0 ng/mL (or 0.17 to 1.0 nmol/L)

Random samples are easier to collect since patients do not need to fast. Recent research shows that random non-fasting C-peptide correlates strongly with stimulated C-peptide from formal testing protocols, making it a practical option for clinical assessment.

However, interpretation requires knowing the concurrent glucose level. A C-peptide of 2.5 ng/mL means something different if blood glucose is 70 mg/dL versus 250 mg/dL. The first scenario suggests appropriate insulin production for a normal glucose level. The second suggests the pancreas is struggling to produce enough insulin despite high blood sugar.

Stimulated C-peptide normal range

Stimulated testing involves giving the patient something to trigger insulin release, either a standardized mixed meal or an injection of glucagon. This stress test evaluates how well the pancreas responds when challenged.

After glucagon stimulation, normal C-peptide levels peak between:

1.5 to 5.0 ng/mL (or 0.5 to 1.65 nmol/L)

The peak typically occurs 6 minutes after glucagon injection. For mixed meal tolerance tests, the peak comes around 90 minutes after eating. Stimulated C-peptide is the most sensitive method for detecting residual beta cell function, which matters greatly when distinguishing between different metabolic conditions and diabetes types.

What low C-peptide levels mean

A low C-peptide indicates that your pancreas is not producing much insulin. This can be normal or abnormal depending on the circumstances.

When low C-peptide is normal

If you have not eaten recently and your blood glucose is in the low-normal range, a low C-peptide makes perfect sense. Your body does not need much insulin when glucose levels are already low, so the pancreas appropriately reduces output.

People who follow ketogenic diets or extended fasting protocols often have lower C-peptide levels during fasting periods. This reflects metabolic adaptation, not disease.

The same applies to individuals using weight loss peptides that reduce appetite and caloric intake.

When low C-peptide is abnormal

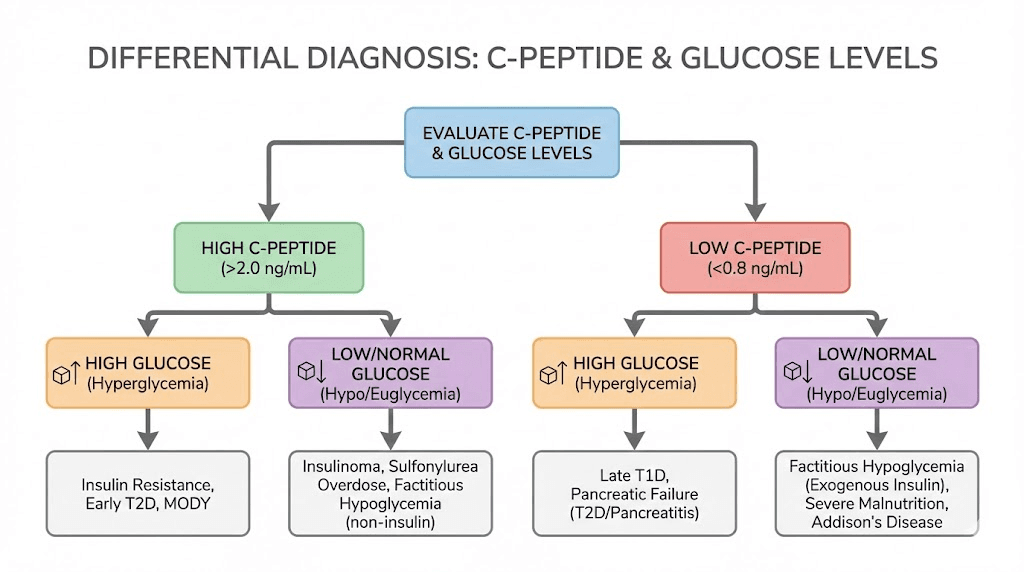

Low C-peptide becomes concerning when it appears alongside normal or high blood glucose. This combination suggests the pancreas cannot produce enough insulin to handle the glucose load. The clinical cutoff that raises serious concern is C-peptide below 0.2 nmol/L (approximately 0.6 ng/mL) in the presence of hyperglycemia.

Type 1 diabetes is the classic cause of very low C-peptide. In this autoimmune condition, the immune system destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. As beta cell destruction progresses, both insulin and C-peptide production decline toward undetectable levels. Most people with established type 1 diabetes have C-peptide levels below 0.2 ng/mL, and many show no detectable C-peptide at all.

Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), sometimes called type 1.5 diabetes, also causes low to low-normal C-peptide levels. Unlike classical type 1 diabetes that appears suddenly in childhood, LADA progresses more slowly in adults. Initial C-peptide levels may appear normal but decline over time as autoimmune destruction continues. Understanding LADA matters for people exploring peptide therapies or other treatments, since the underlying mechanism differs from typical type 2 diabetes.

Advanced type 2 diabetes can eventually cause low C-peptide as well. After 10 to 15 years of disease, progressive beta cell exhaustion leaves some people with type 2 diabetes requiring insulin, with C-peptide levels that look similar to type 1. This is sometimes called pancreatic burnout.

Exogenous insulin use produces the specific pattern of low C-peptide with high insulin. Since injected insulin contains no C-peptide, someone taking insulin shows high total insulin but low C-peptide. This pattern helps doctors identify whether hypoglycemia comes from excessive insulin use, either therapeutic or surreptitious.

Other causes of low C-peptide include pancreatitis or pancreatic surgery that removes insulin-producing tissue, Addison's disease affecting adrenal function, and certain liver diseases.

C-peptide thresholds for type 1 diabetes

The clinical threshold most associated with type 1 diabetes is C-peptide less than 0.2 nmol/L (about 0.6 ng/mL). Below this level, endogenous insulin production is considered severely deficient, consistent with the extensive beta cell destruction seen in type 1 diabetes.

However, context matters.

A person newly diagnosed with diabetes might have C-peptide levels above this threshold while still having type 1 disease, because complete beta cell destruction takes time. The diagnostic accuracy of C-peptide improves when measured 3 to 5 years after diagnosis, by which point true type 1 diabetes has typically progressed to very low or undetectable levels.

What high C-peptide levels mean

Elevated C-peptide indicates that your pancreas is producing above-normal amounts of insulin. This usually reflects one of several situations: insulin resistance, excess food intake, or a tumor that produces insulin.

Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes

The most common cause of high C-peptide is insulin resistance. When your cells do not respond efficiently to insulin, your pancreas compensates by producing more. In early type 2 diabetes and prediabetes, fasting C-peptide levels often exceed 3.0 ng/mL, with stimulated levels going much higher.

This compensatory hyperinsulinemia represents the body's attempt to overcome cellular resistance and maintain normal blood glucose. It works for a while. Eventually, the beta cells cannot keep up, C-peptide levels may normalize or even fall, and blood glucose rises. This progression explains why some people with longstanding type 2 diabetes need insulin therapy.

High C-peptide in the context of insulin resistance often appears alongside other metabolic markers: elevated fasting glucose, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, central obesity, and high blood pressure. The combination defines metabolic syndrome, a cluster of risk factors that weight management strategies and targeted peptide protocols can help address.

Insulinoma

Insulinoma is a rare pancreatic tumor that produces excess insulin. These tumors cause hypoglycemia because insulin levels stay elevated even when blood glucose drops to dangerous levels. Normally, low blood glucose should suppress insulin release. In insulinoma, this feedback mechanism fails.

The diagnostic picture shows: blood glucose below 55 mg/dL, insulin level at least 3 μU/mL, C-peptide at least 0.6 ng/mL, and beta-hydroxybutyrate below 2.7 mmol/L. The C-peptide elevation confirms that the high insulin is endogenous, not from injected insulin.

Most insulinomas are benign and can be surgically removed. About 80% are single tumors. The gold standard diagnostic test is a 72-hour supervised fast, during which patients with insulinoma will develop hypoglycemia with inappropriately elevated insulin and C-peptide.

Sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycemia

Sulfonylureas are diabetes medications that stimulate insulin secretion. Accidental overdose or surreptitious use can cause severe hypoglycemia with elevated C-peptide and insulin. The pattern mimics insulinoma, making the distinction challenging.

The key differentiator is a sulfonylurea drug screen.

If positive, it confirms the medication is causing the hypoglycemia rather than a tumor. Insulin levels in sulfonylurea overdose tend to be extremely high, often above 100 μU/mL, while insulinomas typically produce more modest elevations.

For researchers and individuals working with various therapeutic peptides, understanding these distinctions matters when interpreting metabolic test results that might be affected by different compounds.

Other causes of high C-peptide

Beyond insulin resistance and tumors, elevated C-peptide can result from:

Kidney disease: Impaired renal clearance causes C-peptide accumulation. Levels can rise 2 to 5 times normal in moderate to severe CKD.

Cushing syndrome: Excess cortisol promotes insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia.

Obesity: Independent of diabetes, obesity correlates with higher C-peptide due to increased insulin demand.

Acromegaly: Excess growth hormone causes insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia.

Recent meals: C-peptide rises normally after eating. Very high postprandial levels might simply reflect a large carbohydrate-rich meal rather than disease.

C-peptide testing for diabetes classification

One of the most important clinical uses of C-peptide is distinguishing between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. This distinction matters because treatment strategies differ significantly.

Type 1 diabetes C-peptide patterns

Type 1 diabetes results from autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells. Without beta cells, neither insulin nor C-peptide can be produced. The characteristic C-peptide pattern in type 1 diabetes is:

Low to undetectable levels, typically below 0.2 nmol/L (0.6 ng/mL), that persist regardless of glucose levels or stimulation testing. Even when blood glucose is high, which should trigger insulin release in a normal pancreas, C-peptide remains low because the beta cells are gone.

At diagnosis, some residual C-peptide may be present during the honeymoon period when some beta cells still function. This residual function typically declines over 1 to 3 years. After 5 years of type 1 diabetes, detectable C-peptide is unusual and suggests alternative diagnoses.

Type 2 diabetes C-peptide patterns

Type 2 diabetes begins with insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia.

The characteristic C-peptide pattern shows:

Normal to elevated levels, often above 2.0 ng/mL fasting, with robust responses to stimulation. The pancreas still produces insulin, it just does not work efficiently at target tissues.

Over many years, progressive beta cell failure can occur. When this happens, C-peptide levels decline and may eventually fall into the range seen with type 1 diabetes. This progression typically takes 10 to 20 years.

LADA and the diagnostic gray zone

Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults presents a diagnostic challenge. These patients are adults with autoimmune diabetes that progresses more slowly than classical type 1 diabetes. They often get misdiagnosed as type 2 initially.

LADA patients typically show:

Low-normal C-peptide levels at diagnosis, usually below the median for type 2 diabetes. Positive tests for diabetes autoantibodies, especially GAD antibodies. Initial response to oral diabetes medications that wanes over time. Progressive decline in C-peptide over months to years.

An international expert panel established C-peptide thresholds for LADA management:

C-peptide below 0.3 nmol/L: Treat like type 1 diabetes with multiple daily insulin injections.

C-peptide 0.3 to 0.7 nmol/L: Gray zone requiring individualized therapy, possibly combining insulin with other treatments.

C-peptide above 0.7 nmol/L: Can initially follow type 2 diabetes protocols, with monitoring for decline.

MODY and genetic diabetes

Maturity onset diabetes of the young encompasses genetic forms of diabetes caused by specific gene mutations. Unlike type 1, MODY is not autoimmune. Unlike type 2, it typically appears in lean young people with strong family histories.

C-peptide in MODY is usually:

Detectable, even years after diagnosis. Stable over time rather than declining. Higher than expected for type 1 diabetes despite young age at onset.

A serum C-peptide above 0.2 nmol/L (0.6 ng/mL) with glucose above 144 mg/dL, persisting 3 to 5 years after diagnosis, strongly suggests MODY rather than type 1 diabetes. Genetic testing confirms the specific mutation and guides treatment. Some MODY types respond well to sulfonylureas rather than insulin.

For individuals researching peptide applications and other therapeutic options, understanding these diabetes subtypes helps contextualize how different metabolic states might affect responses to various treatments.

C-peptide test types and procedures

Several different C-peptide test formats exist, each with specific applications, advantages, and limitations. Understanding these helps you know what to expect and how to interpret results.

Fasting C-peptide blood test

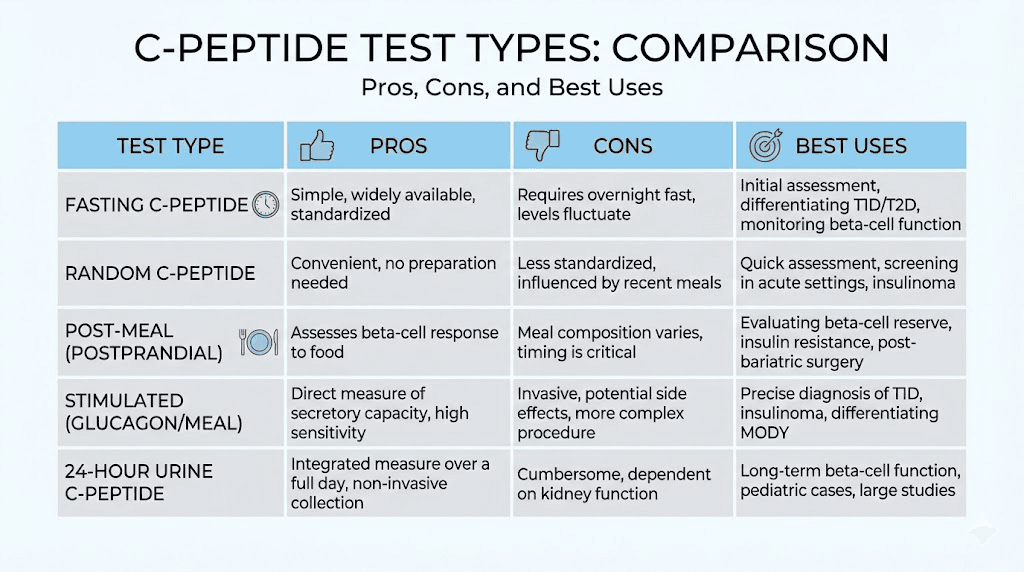

The fasting test requires 8 to 12 hours without food or caloric beverages before blood draw. Water is allowed. This provides a baseline assessment of insulin production under unstressed conditions.

Preparation: Fast overnight, typically scheduling the blood draw first thing in the morning. Inform your healthcare provider about all medications, especially diabetes drugs that might affect results.

Procedure: Standard venipuncture collects a blood sample. The draw takes only a few minutes. Results typically return within 1 to 5 days depending on the laboratory.

Best for: Baseline assessment, monitoring beta cell function over time, screening for insulin production problems.

Limitations: Less sensitive than stimulated testing for detecting subtle deficits. Results can vary with fasting duration.

Random C-peptide blood test

Random testing collects blood without regard to eating or fasting. This practical approach works well for routine monitoring.

Preparation: None required. Can be done at any clinic visit.

Procedure: Standard blood draw. Ideally, a concurrent glucose level should be measured to aid interpretation.

Best for: Convenient monitoring, screening when fasting is impractical, clinical visits where fasting was not planned.

Limitations: Results vary widely depending on recent food intake. Requires concurrent glucose for meaningful interpretation.

Glucagon stimulation test

Glucagon stimulation provides a standardized stress test that maximally challenges the pancreas. An injection of glucagon triggers insulin and C-peptide release, allowing assessment of peak beta cell capacity.

Preparation: Typically an overnight fast. Stop certain diabetes medications as directed.

Procedure: Baseline blood draw, then intravenous glucagon injection (usually 1 mg). Timed blood samples at 2, 4, 6, and sometimes 10 minutes. Peak C-peptide typically occurs around 6 minutes.

Best for: Definitive assessment of beta cell reserve, distinguishing type 1 from type 2 diabetes, evaluating LADA and MODY candidates.

Limitations: Requires clinic time and multiple blood draws. Glucagon can cause nausea in some people. More expensive than single-sample tests.

Mixed meal tolerance test

The MMTT uses a standardized liquid meal (like Boost or Ensure) to stimulate physiological insulin release. It mimics real-world eating conditions.

Preparation: Overnight fast. Stop certain medications as directed.

Procedure: Baseline blood draw, drink the standardized meal, then timed blood samples at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes. Peak C-peptide typically occurs around 90 minutes.

Best for: Research settings, detailed metabolic studies, situations where physiological stimulation is preferred over pharmacological.

Limitations: Time-intensive, requires multiple blood draws, primarily used in research rather than clinical practice.

Urine C-peptide testing

C-peptide can also be measured in urine, either as a 24-hour collection or as a spot urine sample corrected for creatinine (UCPCR).

Preparation: For 24-hour collection, you must collect all urine over a full day. For spot UCPCR, preferably a second-void morning sample.

Procedure: Non-invasive collection. The laboratory measures C-peptide concentration and normalizes to creatinine excretion.

Best for: Children where blood draws are difficult, situations where non-invasive testing is strongly preferred, research applications.

Limitations: Less sensitive than serum testing. Unreliable with any degree of kidney impairment. 24-hour collections are cumbersome and prone to incomplete collection errors.

Factors that affect C-peptide results

Many variables can influence your C-peptide level beyond actual beta cell function. Understanding these helps avoid misinterpretation.

Timing relative to meals

C-peptide rises after eating as the pancreas releases insulin to handle incoming glucose. Peak levels occur 60 to 90 minutes postprandially, potentially 3 to 4 times higher than fasting values. A C-peptide drawn shortly after a large meal tells you nothing about baseline function.

For meaningful results, either fast appropriately before testing or document exactly when you last ate so the result can be interpreted in context.

Kidney function

As discussed earlier, impaired kidney function causes C-peptide accumulation. In moderate CKD (eGFR 30-60), C-peptide levels run about 2 times normal. In severe CKD (eGFR below 30), levels can be 3 to 5 times elevated.

Any C-peptide interpretation in someone with known kidney disease must account for reduced clearance. The laboratory reference range does not apply directly. Clinicians may use adjustment formulas or simply note that the result likely overestimates true insulin production.

Medications

Several medications affect C-peptide levels:

Sulfonylureas: Dramatically increase C-peptide by stimulating insulin secretion.

Meglitinides: Similar to sulfonylureas, they boost insulin release.

GLP-1 agonists: Including semaglutide and related compounds, these increase glucose-dependent insulin secretion, raising C-peptide when glucose is elevated but having less effect during fasting.

Insulin: Exogenous insulin suppresses endogenous production through negative feedback, potentially lowering C-peptide.

Corticosteroids: Chronic use causes insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia, raising C-peptide.

Inform your healthcare provider about all medications before C-peptide testing. Some may need to be held temporarily for accurate results.

Body weight and composition

Obesity independently correlates with higher C-peptide levels. Increased adipose tissue creates insulin resistance, requiring more insulin production to maintain glucose homeostasis. People interested in body composition optimization and fat loss protocols may see their C-peptide levels change as body composition improves.

Physical activity

Acute exercise increases insulin sensitivity temporarily, potentially lowering the insulin and C-peptide response to subsequent meals.

Chronic exercise training also improves insulin sensitivity, which can reduce baseline C-peptide over time in people with insulin resistance.

Stress and illness

Acute illness, surgery, and severe stress trigger counter-regulatory hormones (cortisol, glucagon, catecholamines) that raise blood glucose and increase insulin demand. C-peptide may be elevated during these periods due to the metabolic stress response rather than underlying pathology.

Laboratory variability

Different laboratories use different assays with different calibrations. A C-peptide of 1.5 ng/mL at one lab might not mean exactly the same thing as 1.5 ng/mL at another. When tracking C-peptide over time, try to use the same laboratory consistently. If you must change labs, interpret trends cautiously.

C-peptide in hypoglycemia investigation

Low blood sugar episodes require careful investigation to identify the cause. C-peptide plays a central role in this workup because it helps distinguish between different mechanisms of hypoglycemia.

The Whipple triad

Before investigating hypoglycemia, clinicians confirm three criteria known as the Whipple triad:

1. Symptoms consistent with low blood sugar (confusion, sweating, shakiness, hunger, palpitations)

2. Documented low blood glucose at the time of symptoms (typically below 55 mg/dL)

3. Relief of symptoms when blood glucose is restored

Without all three elements, the diagnosis of true hypoglycemia is uncertain, and extensive workup may not be warranted.

C-peptide and insulin patterns in hypoglycemia

The combination of C-peptide and insulin levels during a hypoglycemic episode points toward specific diagnoses:

High insulin, high C-peptide: Endogenous hyperinsulinism. The body is making too much insulin. Causes include insulinoma, sulfonylurea use, and rare conditions like nesidioblastosis.

High insulin, low C-peptide: Exogenous insulin. Someone is taking or injecting insulin, whether therapeutic or surreptitious. Since commercial insulin contains no C-peptide, this pattern is diagnostic.

Low insulin, low C-peptide: Appropriate suppression. Insulin production has appropriately shut down in response to low glucose. The hypoglycemia must be coming from a non-insulin-mediated cause (liver disease, adrenal insufficiency, sepsis, alcohol, certain tumors producing IGF-like substances).

The 72-hour fast for insulinoma

When insulinoma is suspected, the gold standard diagnostic test is a supervised 72-hour fast in a hospital setting. During this time, patients can drink only calorie-free beverages while blood glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and proinsulin are monitored every 4 to 6 hours (more frequently if glucose drops).

Diagnostic criteria during the fast:

Blood glucose below 55 mg/dL

Insulin at least 3 μU/mL (inappropriately elevated for the low glucose)

C-peptide at least 0.6 ng/mL (0.2 nmol/L)

Proinsulin at least 5 pmol/L

Beta-hydroxybutyrate below 2.7 mmol/L (indicating insulin is suppressing ketogenesis)

Negative sulfonylurea screen

Most patients with insulinoma develop hypoglycemia within 24 to 48 hours of fasting. Healthy people can fast 72 hours without significant hypoglycemia because their insulin secretion appropriately suppresses.

Factitious hypoglycemia

Some individuals induce hypoglycemia intentionally by injecting insulin or taking insulin secretagogues. This can occur in healthcare workers with access to medications, family members of diabetics, or people with certain psychiatric conditions.

Detecting factitious hypoglycemia requires laboratory testing during a symptomatic episode:

Insulin injection: High insulin, very low C-peptide, negative drug screen.

Sulfonylurea ingestion: High insulin, high C-peptide (looks like insulinoma), positive sulfonylurea screen.

The sulfonylurea screen is essential when C-peptide is elevated because, without it, you cannot distinguish medication-induced hypoglycemia from insulinoma.

Clinical applications beyond diabetes

While diabetes classification and hypoglycemia investigation are the primary uses, C-peptide measurement has other clinical applications worth understanding.

Monitoring beta cell function in type 1 diabetes

Even in established type 1 diabetes, residual C-peptide matters. Patients with detectable C-peptide, even at very low levels, tend to have:

Better glucose control with less hypoglycemia

Lower rates of long-term complications

Easier diabetes management

Research into preserving beta cell function in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes uses C-peptide as the primary outcome measure. Any intervention that maintains or increases C-peptide production is potentially slowing the autoimmune destruction.

Evaluating insulin requirements

C-peptide levels help predict whether patients with diabetes will need insulin therapy and how much. People with preserved endogenous insulin production (higher C-peptide) typically require lower doses of exogenous insulin and may respond to non-insulin therapies that would fail in someone with no remaining beta cell function.

For those exploring peptide therapy options or other metabolic interventions, baseline C-peptide provides important information about the underlying metabolic state and what types of treatments might be most appropriate.

Post-pancreatectomy assessment

Patients who undergo partial pancreatectomy for tumors or chronic pancreatitis lose some insulin-producing capacity. C-peptide testing after surgery helps determine how much beta cell function remains and whether diabetes management will be needed.

Research applications

C-peptide serves as an endpoint in numerous research contexts:

Clinical trials for type 1 diabetes prevention or reversal therapies

Studies of islet cell transplantation success

Evaluation of stem cell-derived beta cell therapies

Metabolic research on peptide mechanisms and insulin dynamics

Assessment of peptide safety and metabolic effects

C-peptide as a potential therapeutic

Interestingly, C-peptide itself may have biological activity beyond serving as a marker.

Research suggests C-peptide can improve kidney function, nerve health, and blood flow in people with diabetes. While not yet approved as a therapeutic, C-peptide replacement is an active area of investigation.

Interpreting your C-peptide results

When you receive your C-peptide results, consider the following framework for interpretation.

Step 1: Note the test conditions

Was this a fasting, random, or stimulated sample? The reference range and interpretation differ based on test type. A result of 1.5 ng/mL means something different in each context.

Step 2: Check concurrent glucose

C-peptide should always be interpreted alongside glucose. The pancreas should produce more insulin when glucose is high and less when glucose is low. An appropriate C-peptide matches the glucose level present at the time of the test.

Low C-peptide with high glucose: Problem with insulin production

High C-peptide with low glucose: Excess insulin production

C-peptide proportional to glucose: Appropriate regulation

Step 3: Consider kidney function

If you have known kidney disease, your C-peptide may be elevated due to reduced clearance rather than increased production. Ask your healthcare provider to factor in your eGFR when interpreting results.

Step 4: Account for medications

Sulfonylureas, GLP-1 agonists, and other medications affect C-peptide. Results obtained while taking these medications reflect drug-stimulated production, not baseline function.

Step 5: Look at trends

A single C-peptide value provides a snapshot. Serial measurements over months or years reveal trends that matter more than any individual number. Declining C-peptide over time in someone with diabetes suggests progressive beta cell failure.

Step 6: Correlate with clinical picture

Laboratory results never exist in isolation. Your age, weight, family history, symptoms, other lab values, and medication response all contribute to the full picture. C-peptide is one piece of evidence, not the whole story.

When to get C-peptide tested

Not everyone needs C-peptide testing. Here are situations where it provides valuable information:

Clarifying diabetes type

If you were diagnosed with diabetes but the type is uncertain, perhaps because you are an adult with features of both type 1 and type 2, C-peptide combined with autoantibody testing helps clarify the diagnosis. This matters because treatment strategies differ significantly.

Unexplained hypoglycemia

If you experience recurrent low blood sugar episodes without a clear cause, C-peptide during a hypoglycemic episode helps identify the mechanism. This is especially important if you do not have diabetes and are not taking diabetes medications.

Monitoring beta cell function

For people with type 1 diabetes, periodic C-peptide testing tracks residual beta cell function.

This information helps predict hypoglycemia risk and guide treatment intensity.

Evaluating response to therapy

In type 2 diabetes, C-peptide can assess whether treatments are preserving or depleting beta cell function over time. Some patients want this monitoring to guide long-term management decisions.

Research participation

Many diabetes prevention and treatment trials use C-peptide as an outcome measure. If you are considering participating in research, you may undergo C-peptide testing as part of the protocol.

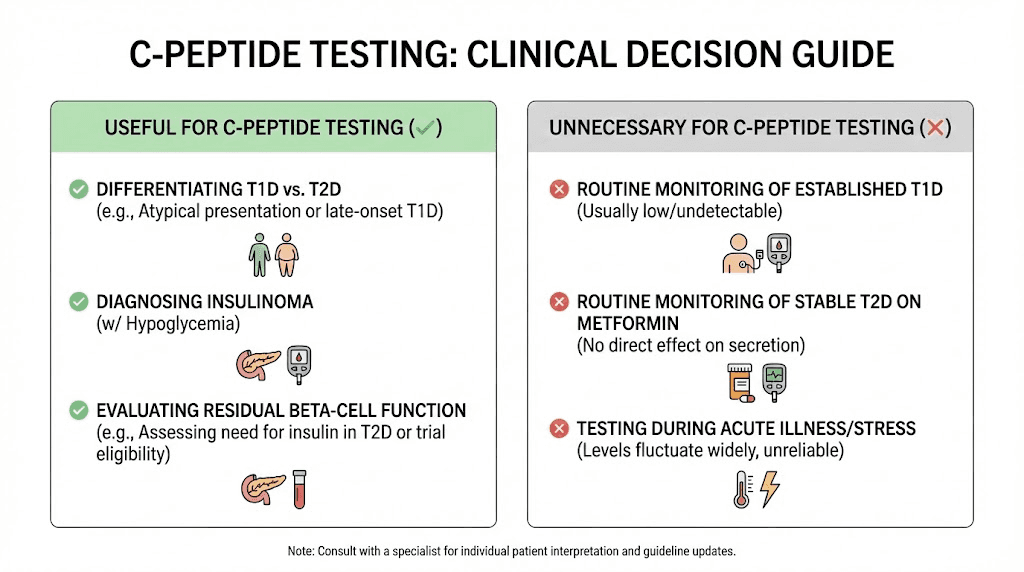

Not routinely needed

For straightforward type 2 diabetes with classic presentation, routine C-peptide testing usually adds little value. The diagnosis is clear from clinical criteria, and management follows standard protocols regardless of C-peptide level.

Similarly, for well-controlled type 1 diabetes diagnosed years ago, C-peptide testing mainly confirms what you already know (production is minimal). It may have research value but limited clinical utility.

C-peptide reference values by laboratory

Reference ranges vary between laboratories. Here are typical ranges from several major reference laboratories to illustrate the variation:

Quest Diagnostics fasting: 0.8 to 3.5 ng/mL

LabCorp fasting: 0.8 to 3.1 ng/mL

Mayo Clinic fasting: 0.8 to 3.5 ng/mL

Cleveland Clinic fasting: 0.5 to 2.0 ng/mL

The variation reflects different assay methods, calibration standards, and population norms. Always interpret your result against the specific reference range provided on your lab report, not against ranges from other sources.

Unit conversion

C-peptide results may be reported in different units:

ng/mL to nmol/L: Multiply by 0.33

nmol/L to ng/mL: Multiply by 3.0

pmol/L to nmol/L: Divide by 1000

Example: 1.5 ng/mL equals approximately 0.5 nmol/L

When comparing results between laboratories or studies, ensure you are using the same units.

Advances in C-peptide testing

C-peptide assay technology continues to evolve, improving clinical utility.

Ultrasensitive assays

Modern ultrasensitive C-peptide assays can detect levels as low as 0.0015 to 0.0025 nmol/L, far below the limits of older tests. These assays reveal that many people with longstanding type 1 diabetes have trace residual C-peptide production previously thought to be absent. This residual function, even at very low levels, may have clinical significance for hypoglycemia risk and complication prevention.

Point-of-care testing

Researchers are developing point-of-care C-peptide tests that could provide results in minutes rather than days. This would enable real-time decision-making in clinical settings, particularly useful for hypoglycemia investigation and diabetes classification.

Urine UCPCR as alternative

The urinary C-peptide creatinine ratio provides a non-invasive alternative to blood testing. While less sensitive than serum C-peptide, UCPCR has practical advantages for populations where blood draws are difficult, such as children with needle phobia. Ongoing research aims to better standardize UCPCR interpretation.

Putting it all together

C-peptide testing provides a window into your pancreatic beta cell function that no other test can match. Normal fasting levels between 0.5 and 2.0 ng/mL suggest healthy insulin production. Levels below 0.2 nmol/L indicate severe insulin deficiency. Elevated levels point toward insulin resistance or, rarely, insulin-producing tumors.

Context is everything. Your C-peptide result needs interpretation alongside glucose levels, kidney function, medications, and clinical presentation. A single number without context can mislead more than inform.

For those navigating peptide research and metabolic health optimization, understanding C-peptide helps contextualize how your body produces and uses insulin. Whether you are investigating unexplained symptoms, clarifying a diabetes diagnosis, or simply understanding your metabolic health, this marker provides unique and valuable information.

SeekPeptides members access comprehensive resources on peptide applications, research summaries, and evidence-based protocols for metabolic optimization. Our guides cover everything from getting started with peptides to advanced topics like peptide stacking and cycle planning.

Frequently asked questions

What is a normal C-peptide level?

Normal fasting C-peptide typically ranges from 0.5 to 2.0 ng/mL (0.17 to 0.66 nmol/L). Random non-fasting levels can go up to 3.0 ng/mL.

Reference ranges vary between laboratories, so always compare your result to the specific range on your report. For those researching peptide dosing and metabolic markers, knowing your baseline C-peptide provides useful context.

What does low C-peptide mean?

Low C-peptide indicates reduced insulin production by the pancreas. This is expected in type 1 diabetes where beta cells are destroyed. It can also occur in advanced type 2 diabetes, LADA, or after pancreatectomy. A low C-peptide with low glucose is normal and appropriate. A low C-peptide with high glucose suggests insulin deficiency requiring treatment.

What does high C-peptide mean?

Elevated C-peptide usually indicates insulin resistance, where the pancreas must produce extra insulin to maintain glucose control. This is common in type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, and obesity. Rarely, high C-peptide with hypoglycemia suggests insulinoma or sulfonylurea use. Kidney disease can also elevate C-peptide through reduced clearance.

Can C-peptide testing distinguish type 1 from type 2 diabetes?

Yes, C-peptide is useful for diabetes classification, especially in ambiguous cases. Type 1 diabetes typically shows very low or undetectable C-peptide (below 0.2 nmol/L), while type 2 usually shows normal or elevated levels. The test works best 3 to 5 years after diagnosis, once any honeymoon period has passed. Autoantibody testing provides complementary information.

Do I need to fast for a C-peptide test?

It depends on the test ordered. Fasting C-peptide requires 8 to 12 hours without food. Random C-peptide can be done anytime. Stimulated tests have specific preparation requirements. Ask your healthcare provider which test was ordered and follow their instructions. For most diagnostic purposes, fasting or stimulated tests provide more interpretable results than random samples.

How does C-peptide relate to insulin?

C-peptide and insulin are produced in equal amounts when your pancreas makes insulin. They are released together into the bloodstream. C-peptide is preferred for measuring insulin production because it is not affected by injected insulin, has a longer half-life, and experiences more consistent clearance. People using peptide calculators and other metabolic tools should understand this relationship.

Can kidney disease affect C-peptide levels?

Yes, kidney disease significantly affects C-peptide clearance. When kidney function declines, C-peptide accumulates in the blood, potentially rising 2 to 5 times above normal. This can cause falsely elevated readings that do not reflect true insulin production. Clinicians must interpret C-peptide results in the context of kidney function tests.

Is C-peptide testing covered by insurance?

C-peptide testing is typically covered when medically indicated for diabetes classification, hypoglycemia investigation, or other diagnostic purposes. Coverage varies by plan and indication. Check with your insurance provider about specific coverage for the indication your healthcare provider has documented.

In case I don't see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night. Join SeekPeptides.