Jan 26, 2026

Your doctor hands you the lab results. The number next to BNP is higher than the reference range. Your mind races. What does this mean? Is something seriously wrong with your heart?

Take a breath.

A high B-type natriuretic peptide level does not automatically mean heart failure. It does not mean you need emergency care. And it certainly does not mean your life is about to change dramatically. But it does mean something. Your body is sending a signal, and understanding that signal is the first step toward protecting your cardiovascular health.

Here is what most people do not realize. BNP can be elevated for a dozen different reasons beyond heart problems. Age affects it. Gender affects it. Kidney function, lung conditions, certain medications, even your body weight can push that number higher or lower than expected. The challenge is not just knowing your BNP is elevated. The challenge is understanding why, what it actually indicates about your health, and what to do next.

This guide walks through everything. We cover the exact reference ranges by age and sex, the conditions that elevate BNP without any cardiac involvement, how doctors interpret various levels from mildly elevated to severely high, and the evidence-based strategies that can help bring those numbers down when appropriate. Whether you just received concerning lab results or you are tracking your cardiovascular health over time, understanding BNP gives you power. The power to ask the right questions, make informed decisions, and take control of your health.

What is B-type natriuretic peptide and why does it matter

B-type natriuretic peptide is a hormone your heart produces. Specifically, the ventricles, the lower chambers responsible for pumping blood throughout your body, release this protein when they stretch or experience increased pressure. The name sounds complicated, but the function is elegantly simple. BNP acts as your cardiovascular system's distress signal and relief valve rolled into one.

When your heart works harder than it should, it releases more BNP. This hormone then travels through your bloodstream and tells your kidneys to excrete more sodium and water. It also signals your blood vessels to relax and widen. The net effect reduces blood volume, lowers blood pressure, and takes some of the workload off your struggling heart. Think of it as a built-in emergency response system. Your body recognizes cardiac stress and automatically activates mechanisms to protect itself.

Scientists first discovered this peptide in brain tissue, which explains why some sources call it brain natriuretic peptide. However, the heart produces far more BNP than the brain, making it primarily a cardiac hormone. The confusion in naming persists in medical literature, but the function remains the same regardless of what you call it.

Why doctors measure BNP levels

A BNP test gives your healthcare provider a window into how hard your heart is working. When someone arrives at an emergency room with shortness of breath, doctors need to quickly determine whether heart failure is causing the symptoms or whether something else, perhaps a lung condition or anxiety, is responsible. BNP testing helps make that distinction.

The test is particularly valuable because of its negative predictive power. When BNP levels come back low, doctors can confidently rule out heart failure as the cause of symptoms. This prevents unnecessary hospitalizations, reduces healthcare costs, and spares patients from invasive testing they do not need. Studies show diagnostic accuracy around 90% when using established cutoff values.

Beyond diagnosis, BNP helps monitor existing heart conditions. If you have been diagnosed with heart failure, rising BNP levels over time can signal worsening function before symptoms become obvious. Conversely, declining levels often indicate that treatment is working. This makes BNP an excellent tool for adjusting medications and catching problems early.

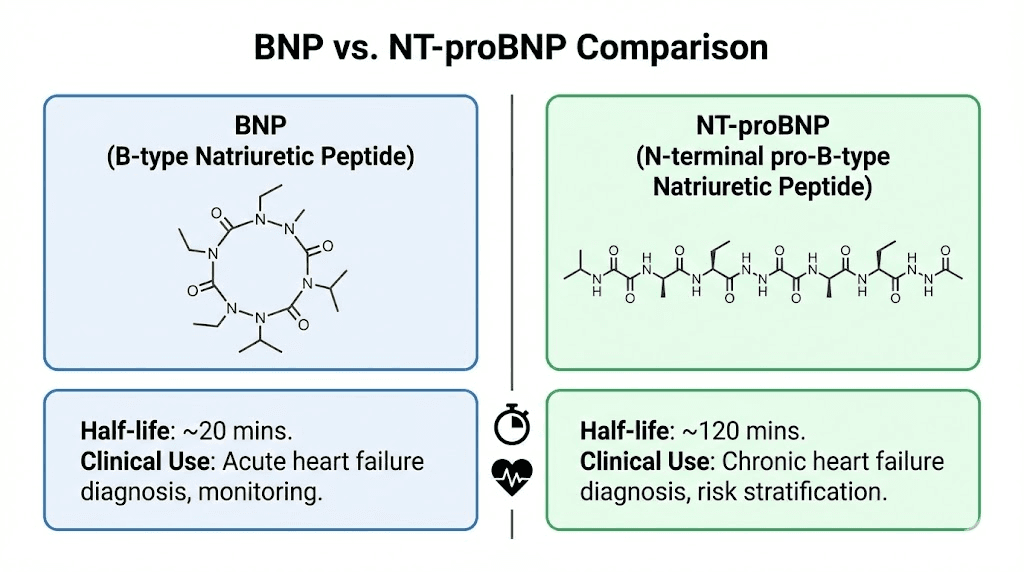

BNP versus NT-proBNP

You might see two different tests on your lab results. BNP and NT-proBNP are related but not identical. When your heart cells produce the BNP hormone, they actually create a larger precursor molecule first. This molecule then splits into two pieces. One piece is the active BNP hormone that relaxes blood vessels and promotes sodium excretion. The other piece is called NT-proBNP, which stands for N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

NT-proBNP has no biological activity. It does nothing in your body. But it sticks around longer in your bloodstream, with a half-life of 90 to 120 minutes compared to only 20 minutes for active BNP. This longer half-life makes NT-proBNP easier to measure accurately and more sensitive for detecting early stages of heart stress. Many hospitals now prefer NT-proBNP testing for these reasons.

The reference ranges differ substantially between the two tests. A normal BNP is generally below 100 picograms per milliliter, while a normal NT-proBNP depends heavily on age but typically runs under 125 pg/mL for people under 75 and under 450 pg/mL for those older. Make sure you know which test your doctor ordered before comparing your results to any reference values.

Normal BNP levels by age and gender

Understanding whether your BNP is truly elevated requires context. A reading of 90 pg/mL might be perfectly normal for a 75-year-old woman but concerning in a 35-year-old man. Age and biological sex both significantly influence baseline BNP concentrations, and failing to account for these factors leads to misdiagnosis.

Research consistently shows that BNP levels increase with age. This happens for several reasons. Older hearts are stiffer. They have to work harder against blood vessels that have lost some of their youthful elasticity. The kidneys, which help clear BNP from the bloodstream, become less efficient over time. All of these factors contribute to naturally higher readings in older populations.

Women typically have higher BNP levels than men at any given age. The exact mechanism remains under investigation, but estrogen appears to play a role. Some researchers believe estrogen directly stimulates BNP production, while testosterone may suppress it. This explains why the gender gap tends to narrow somewhat after menopause when estrogen levels decline.

Age-specific reference ranges for BNP

General population studies suggest the following approximate ranges for BNP, though individual laboratories may use slightly different values:

Adults under 45 years typically show BNP levels below 100 pg/mL, with most readings falling well under 50 pg/mL in healthy individuals. Those between 45 and 54 may have upper normal limits extending to around 140 pg/mL. Between ages 55 and 64, normal can reach up to 180 pg/mL. For people 65 to 74, levels up to 230 pg/mL may still fall within normal parameters. And for those 75 and older, especially women, readings up to 850 pg/mL can sometimes occur without indicating pathology.

These ranges highlight why a blanket cutoff of 100 pg/mL, while useful for acute emergency evaluation, fails to account for the nuances of individual physiology. Your doctor should interpret your results in the context of your age, sex, symptoms, and overall clinical picture.

NT-proBNP reference ranges

Because NT-proBNP circulates at higher concentrations and for longer periods, its reference ranges look different. The Circulation: Heart Failure journal published comprehensive data from over 18,000 individuals showing median and 97.5th percentile values by age and sex.

For men under 30, the median NT-proBNP was just 21 pg/mL, with the upper 97.5th percentile at 104 pg/mL. By ages 50 to 59, median values rose to 38 pg/mL with an upper limit around 195 pg/mL. For men 80 and older, median readings reached 281 pg/mL, and the 97.5th percentile extended to a striking 6,792 pg/mL.

Women showed consistently higher values. Under age 30, the median was 51 pg/mL with an upper limit of 196 pg/mL. At 50 to 59 years, median values were 66 pg/mL with an upper limit of 299 pg/mL. For women 80 and older, median NT-proBNP reached 240 pg/mL, though the upper percentile was somewhat lower than men at 2,704 pg/mL.

Understanding these reference ranges through laboratory testing standards helps you assess whether your elevation is truly abnormal or simply reflects your demographic profile. A 70-year-old woman with an NT-proBNP of 400 pg/mL may be completely healthy, while a 30-year-old man with the same reading warrants immediate investigation.

What causes high BNP levels

The list of conditions that can elevate BNP extends far beyond heart failure. While cardiac dysfunction remains the most common cause of significantly elevated readings, many other factors can push your numbers above the reference range. Understanding these causes helps prevent unnecessary anxiety and guides appropriate medical workup.

Heart-related causes

Heart failure is the condition most strongly associated with elevated BNP. When the heart cannot pump blood efficiently, the ventricles stretch to accommodate the backup of blood. This stretching triggers BNP release. The higher the BNP, the more severe the heart failure tends to be. Studies show that levels above 400 pg/mL strongly suggest acute heart failure in patients with shortness of breath, while levels above 1,000 pg/mL indicate poor prognosis.

But heart failure is not the only cardiac cause. Atrial fibrillation, the irregular heart rhythm that affects millions of people, commonly elevates BNP even without any weakening of the heart muscle. The chaotic electrical activity and rapid ventricular response create wall stress that triggers hormone release. Acute heart attacks raise BNP as damaged tissue releases stored peptide and surviving heart muscle works harder to compensate. Valvular heart disease, where heart valves leak or narrow, forces the ventricles to work harder and therefore produce more BNP. Left ventricular hypertrophy, where the heart muscle thickens in response to chronic high blood pressure, similarly elevates readings.

Even myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle often caused by viral infections, can temporarily spike BNP levels. Understanding your inflammation markers alongside BNP provides a more complete picture of cardiac health.

Kidney disease and BNP elevation

Your kidneys play a crucial role in clearing BNP from your bloodstream. When kidney function declines, BNP accumulates regardless of what your heart is doing. This creates a significant diagnostic challenge because both heart failure and kidney disease can cause similar symptoms, including fatigue, swelling, and shortness of breath.

Studies show that patients with chronic kidney disease consistently have higher BNP and NT-proBNP levels compared to those with normal kidney function. The worse the kidney function, measured by glomerular filtration rate, the higher the baseline natriuretic peptide levels. Some patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis may have NT-proBNP levels exceeding 70,000 pg/mL without any cardiac abnormality.

This kidney-BNP relationship means doctors must consider renal function when interpreting your results. If your creatinine is elevated or your GFR is reduced, some portion of your BNP elevation may be attributable to impaired clearance rather than cardiac stress. Specialized formulas now exist to adjust BNP interpretation based on kidney function.

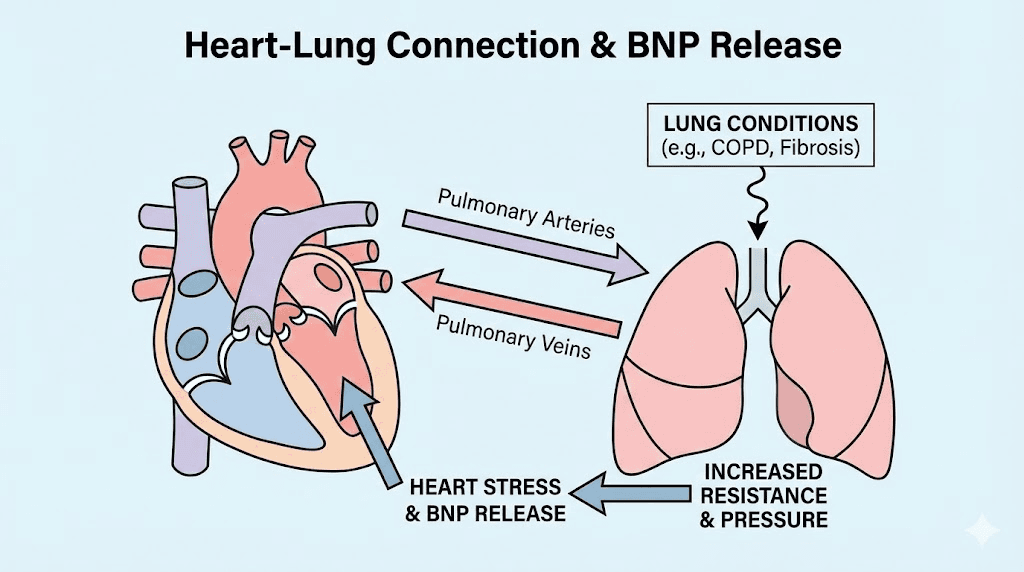

Lung conditions that raise BNP

The heart and lungs work as an interconnected system. When lung disease increases pressure in the pulmonary arteries, the right side of the heart must pump harder against that resistance. This right ventricular strain triggers BNP release just as left ventricular stress does.

Pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in the lung arteries, can dramatically elevate BNP within hours. The sudden obstruction forces the right ventricle to generate much higher pressures than normal. This acute stress releases a surge of natriuretic peptide. In fact, BNP levels help doctors assess the severity of pulmonary embolism and predict which patients need more aggressive treatment.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affects BNP through multiple mechanisms. The constant strain of breathing against narrowed airways, the low oxygen levels that stress the heart, and the pulmonary hypertension that often develops over time all contribute to elevated readings. Severe pneumonia similarly stresses the cardiopulmonary system and raises BNP. Even sleep apnea, where breathing repeatedly stops during sleep, causes nighttime surges in cardiac stress that can manifest as elevated morning BNP levels.

Other non-cardiac causes

Sepsis, a severe body-wide response to infection, dramatically elevates BNP through mechanisms that are not fully understood. The systemic inflammation, changes in blood flow, and direct effects of bacterial toxins on heart cells all likely contribute. Critically ill patients in intensive care units frequently have elevated BNP regardless of their underlying cardiac status.

Hyperthyroidism increases metabolic demand throughout the body, forcing the heart to work harder. This elevated workload triggers BNP release. Conversely, severe hypothyroidism can also raise BNP by causing pericardial effusion, where fluid accumulates around the heart.

Certain autoimmune conditions, including systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, have been associated with elevated natriuretic peptides even without clinical heart disease. The chronic inflammation and immune system dysfunction may affect cardiac cells directly.

Liver cirrhosis causes complex circulatory changes that can elevate BNP. The accumulation of fluid in the abdomen, the shunting of blood through abnormal vessels, and the associated kidney dysfunction all contribute.

Medications and BNP

Some medications directly affect BNP levels, complicating interpretation. The most notable example is sacubitril/valsartan, sold under the brand name Entresto, which is used to treat heart failure. This medication works by blocking the enzyme that breaks down BNP. As a result, patients taking this drug have significantly elevated BNP levels that do not reflect worsening heart function. For these patients, NT-proBNP is the preferred monitoring test since it is not affected by this medication.

Conversely, effective heart failure treatment with other medications typically lowers BNP over time. ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and diuretics all reduce cardiac stress and therefore reduce BNP production. A declining BNP in a heart failure patient usually indicates successful treatment.

Interpreting your BNP results

Raw numbers mean little without context. A BNP of 250 pg/mL could represent completely normal variation in an elderly woman, mild elevation worth monitoring in a middle-aged man, or significant abnormality requiring urgent evaluation in a young athlete. Learning to interpret results requires understanding the clinical framework doctors use.

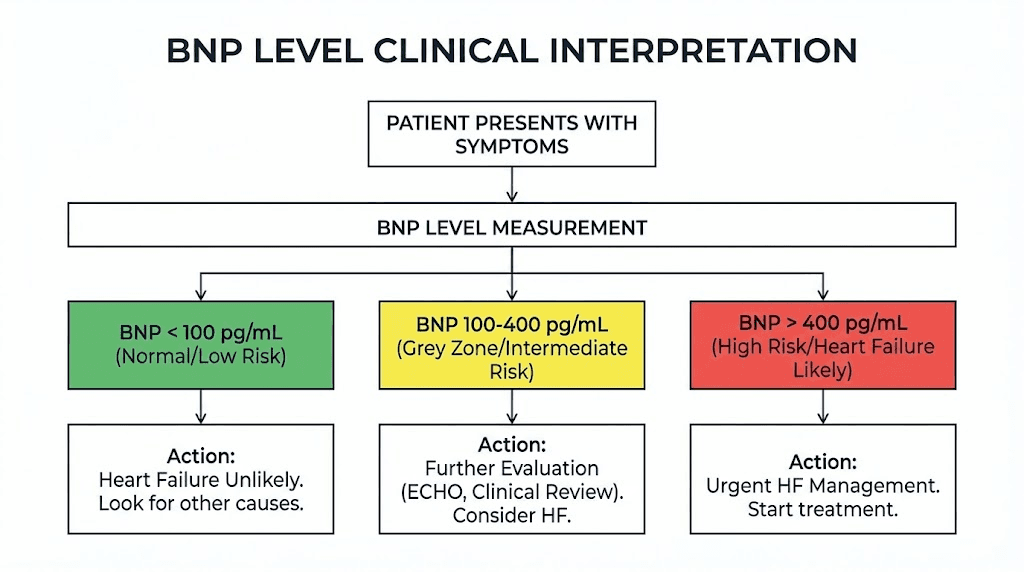

The diagnostic zones

For acute shortness of breath in an emergency setting, doctors typically use a tiered approach. BNP below 100 pg/mL makes heart failure very unlikely, with negative predictive value exceeding 90%. This low reading tells doctors to look elsewhere for the cause of symptoms, perhaps a lung infection, asthma attack, or anxiety.

BNP between 100 and 400 pg/mL falls into a gray zone. Heart failure is possible but not certain. At these levels, doctors must weigh other clinical factors. What do the symptoms look like? Is there swelling in the legs? Are there abnormalities on the echocardiogram? Does the patient have a history of heart disease? The clinical picture determines the next steps, not the BNP alone.

BNP above 400 pg/mL strongly suggests acute heart failure in a symptomatic patient. The positive predictive value at this level is high, though doctors still perform additional testing to confirm the diagnosis and assess severity.

For stable outpatients without acute symptoms, the interpretation differs. BNP below 35 pg/mL or NT-proBNP below 125 pg/mL effectively rules out heart failure. Higher values warrant further investigation but do not necessarily mean immediate treatment is needed.

Severity staging by BNP level

When heart failure is confirmed, BNP levels help stage severity. Some clinicians use the following general framework:

Levels from 100 to 500 pg/mL typically indicate mild dysfunction. The heart is struggling somewhat, but compensatory mechanisms are still effective. Patients often have minimal symptoms at rest but may notice fatigue or breathlessness with exertion. Treatment at this stage focuses on preventing progression.

Levels from 500 to 1,000 pg/mL suggest mild to moderate elevation with more significant cardiac compromise. Symptoms are more apparent. The risk of hospitalization increases. More aggressive medication management becomes necessary.

Levels from 1,000 to 3,000 pg/mL indicate moderate to severe heart failure. These patients often require hospitalization for stabilization. The prognosis becomes more concerning, and doctors may consider advanced therapies including device implantation.

Levels above 4,000 pg/mL represent extreme elevation with grave implications. Patients at these levels often have decompensated heart failure requiring intensive care. Mortality risk is significantly elevated. However, even at these levels, aggressive treatment can sometimes produce dramatic improvement.

Why one test is not enough

BNP provides valuable information but never tells the complete story. Doctors always interpret results alongside other data including physical examination findings, electrocardiogram results, echocardiogram imaging, and patient symptoms.

A high BNP without symptoms might reflect underlying structural heart disease that has not yet manifested clinically. Or it might reflect kidney disease, age-related changes, or other non-cardiac causes. Conversely, a patient with classic heart failure symptoms might have a relatively low BNP if they are obese (adipose tissue reduces BNP) or if they have received recent treatment that temporarily suppressed levels.

Serial measurements over time often provide more insight than any single reading. A patient with a baseline BNP of 200 pg/mL who suddenly jumps to 600 pg/mL is experiencing significant cardiac stress even though 600 pg/mL might not trigger alarm in someone else. Trending your biomarker levels over time reveals patterns that single snapshots miss.

Conditions associated with very high BNP levels

While mild elevations have numerous possible causes, very high BNP levels typically indicate significant pathology. Understanding what drives extreme elevations helps focus diagnostic efforts and guides urgency of treatment.

Acute decompensated heart failure

The most common cause of BNP levels exceeding 1,000 pg/mL is acute decompensated heart failure. This condition occurs when a patient with underlying heart weakness experiences a sudden worsening, often triggered by medication noncompliance, dietary indiscretion involving too much salt, infection, or new arrhythmia.

The heart, already compromised, cannot handle the additional stress. Fluid backs up in the lungs, causing severe shortness of breath. Pressure in the cardiac chambers rises dramatically. The ventricles stretch beyond their normal limits. BNP production surges in response to this crisis.

Patients with decompensated heart failure typically present with obvious symptoms. They cannot lie flat without gasping for air. Their legs and ankles are swollen. They may have pink, frothy sputum from fluid in the lungs. The physical examination usually reveals the diagnosis before any lab results return. But BNP helps confirm the severity and guide treatment intensity.

Acute coronary syndrome

Heart attacks trigger BNP release through several mechanisms. Dying heart tissue releases stored peptide. Surviving heart muscle must work harder to compensate for the damaged areas. The resulting wall stress stimulates ongoing BNP production. And the inflammatory response to cardiac injury may directly stimulate natriuretic peptide synthesis.

BNP levels measured during acute coronary syndrome provide prognostic information. Higher levels at admission predict larger heart attacks, greater likelihood of developing heart failure, and higher mortality. Some hospitals now routinely measure BNP in all chest pain patients to help stratify risk and guide treatment intensity.

The BNP elevation typically peaks 24 to 48 hours after a heart attack and then gradually declines over weeks as the heart heals and adapts. Persistently elevated levels suggest ongoing cardiac remodeling and higher risk of future events.

Severe pulmonary embolism

When a large blood clot lodges in the pulmonary arteries, the right ventricle must suddenly generate much higher pressures to push blood through the obstructed vessels. This acute right heart strain causes immediate BNP release.

In pulmonary embolism, BNP levels help doctors determine who needs aggressive intervention. Patients with massive PE and elevated BNP have significantly higher mortality than those with lower levels. Some may require thrombolytic therapy to dissolve the clot or even surgical removal. BNP helps identify this high-risk group.

Understanding the relationship between cardiovascular stress markers and outcomes helps patients appreciate why doctors pay such close attention to these laboratory values.

Cardiac tamponade and pericardial disease

When fluid accumulates in the sac surrounding the heart, it can compress the cardiac chambers and impair filling. This condition, called cardiac tamponade, creates significant cardiac stress despite technically normal pumping function. BNP rises in response to the compromised hemodynamics.

Chronic pericardial diseases, including constrictive pericarditis where the pericardial sac becomes thick and rigid, similarly elevate BNP. The heart cannot fill properly during relaxation, leading to backup pressure and hormonal release. These conditions require specific treatment different from standard heart failure therapy, making accurate diagnosis essential.

How to lower high BNP levels

Reducing elevated BNP requires addressing the underlying cause. There is no magic pill that simply lowers BNP independent of actual cardiac improvement. When BNP drops, it reflects genuine reduction in cardiac stress. When treatment fails to lower BNP, it often indicates the underlying condition has not improved.

Medical treatment for heart failure

The cornerstone medications for heart failure effectively lower BNP by reducing cardiac workload. ACE inhibitors and ARBs relax blood vessels, making it easier for the heart to pump. This reduced resistance translates to lower wall stress and diminished BNP production. Beta-blockers slow the heart rate and reduce the force of contraction, allowing the heart to work more efficiently rather than harder. Diuretics remove excess fluid, decreasing the blood volume that the heart must pump and reducing the stretch on ventricular walls.

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists like spironolactone and eplerenone work through additional mechanisms that reduce cardiac remodeling and improve outcomes. SGLT2 inhibitors, originally developed for diabetes, have proven remarkably effective in heart failure regardless of diabetic status. These medications reduce hospitalizations and mortality while also lowering natriuretic peptide levels.

The goal of treatment is not specifically to lower BNP. The goal is to improve cardiac function, reduce symptoms, prevent hospitalization, and extend life. BNP decline is simply a marker that confirms these goals are being achieved.

Addressing non-cardiac causes

When kidney disease contributes to BNP elevation, optimizing renal function becomes a priority. This may involve adjusting medications that stress the kidneys, controlling blood pressure to prevent further kidney damage, and managing fluid balance carefully. Dialysis patients may see improved BNP levels with more effective dialysis schedules that better clear the accumulated peptide.

Lung disease treatment indirectly lowers BNP by reducing the strain on the right heart. Treating pulmonary hypertension with targeted medications, optimizing COPD therapy with bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory agents, and treating sleep apnea with CPAP all reduce cardiac stress and therefore BNP production.

Hyperthyroidism treatment normalizes metabolic demand and allows the heart to work at a sustainable pace. As thyroid hormone levels return to normal, cardiac stress diminishes and BNP follows. Similar logic applies to treating any systemic condition that increases cardiac workload.

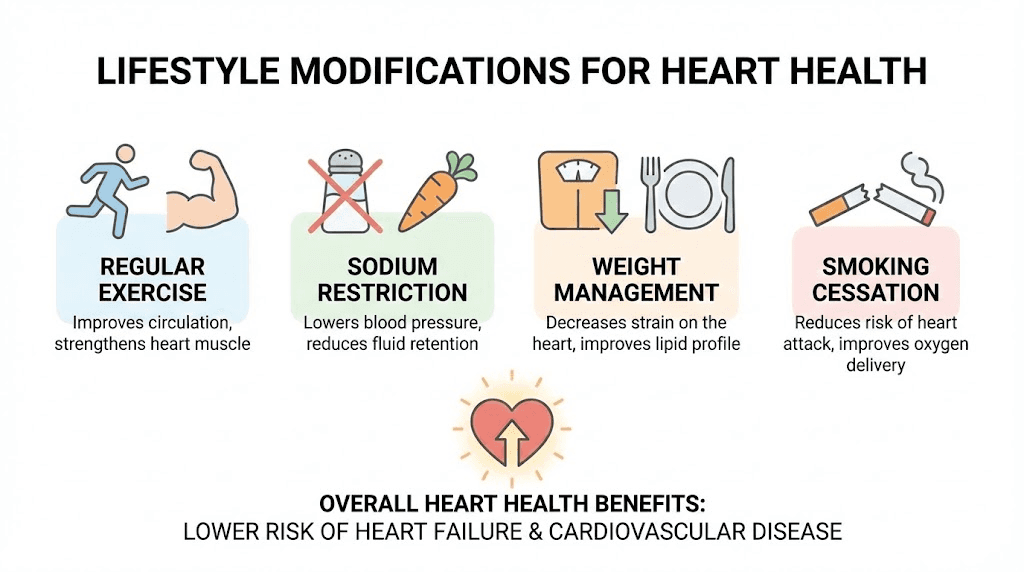

Lifestyle modifications

Beyond medical treatment, lifestyle changes meaningfully impact BNP levels. Sodium restriction reduces fluid retention and therefore reduces the volume load on the heart. Most heart failure patients are advised to limit sodium to 2,000 milligrams daily or less. This seemingly simple intervention can significantly improve symptoms and lower natriuretic peptide levels.

Regular aerobic exercise, appropriately prescribed and monitored, improves cardiac efficiency. The heart becomes a better pump that achieves the same output with less wall stress. Studies consistently show that cardiac rehabilitation and supervised exercise programs improve heart failure outcomes and reduce biomarker levels.

Weight management matters for multiple reasons. Obesity itself is associated with heart failure and elevated cardiac risk. But paradoxically, BNP tends to run lower in obese individuals due to unclear mechanisms. Regardless, achieving a healthy weight reduces the overall burden on the cardiovascular system and improves outcomes.

Alcohol limitation or elimination removes a direct cardiac toxin. Chronic excessive alcohol use can cause a specific form of heart failure called alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Even moderate drinking may worsen existing heart failure. Eliminating alcohol allows the heart to recover and BNP to decline.

Smoking cessation addresses one of the most modifiable cardiovascular risk factors. Tobacco damages blood vessels, accelerates atherosclerosis, increases blood pressure, and reduces oxygen delivery. Quitting smoking improves cardiovascular health through multiple mechanisms and can help normalize elevated biomarkers over time.

Monitoring and follow-up

Tracking BNP trends over time provides valuable feedback about treatment effectiveness. Most cardiologists recommend checking levels at regular intervals, typically every few months for stable patients and more frequently during treatment adjustments or after hospitalizations.

A declining BNP trend indicates successful management. The treatments are working. The heart is adapting and compensating. The prognosis is improving. This feedback helps motivate patients to maintain adherence to medications and lifestyle changes.

A rising BNP despite treatment suggests the underlying condition is worsening. Perhaps the disease is progressing. Perhaps medications need adjustment. Perhaps new problems have developed. This early warning allows intervention before clinical deterioration becomes obvious.

Understanding your personal baseline becomes crucial for accurate interpretation. A BNP that has dropped from 800 to 300 pg/mL represents excellent progress even though 300 still exceeds the general normal range. Conversely, a rise from 100 to 250 pg/mL in the same individual signals a problem even though 250 might not trigger concern in someone else.

BNP and prognosis

Beyond diagnosis, BNP levels predict outcomes. Higher levels at any given time point correlate with higher risk of death, hospitalization, and disease progression. This prognostic value makes BNP useful for identifying patients who need more intensive monitoring and treatment.

What the numbers predict

Large studies have established clear relationships between BNP levels and clinical outcomes. The ADHERE registry, which included over 48,000 heart failure patients, found that admission BNP above 430 pg/mL predicted significantly higher in-hospital mortality. Patients with BNP above 1,700 pg/mL had mortality rates nearly double those with lower levels.

Long-term studies show similar patterns. Patients with BNP levels above 1,000 pg/mL have substantially worse three-year survival compared to those with levels below 200 pg/mL. Even after adjusting for other risk factors like age, kidney function, and heart failure severity, BNP remains an independent predictor of poor outcomes.

This prognostic information helps guide treatment intensity. A patient with very high BNP may benefit from earlier consideration of advanced therapies like implantable defibrillators, cardiac resynchronization devices, or even heart transplant evaluation. Resources can be allocated to those at highest risk.

Response to treatment as a predictor

Perhaps more useful than any single BNP measurement is how levels respond to treatment. Patients whose BNP declines by 30% or more during hospitalization for heart failure have significantly better outcomes than those whose levels remain flat or rise despite treatment.

This treatment response reflects the underlying biology of heart failure. When therapy works, cardiac stress diminishes, BNP production falls, and the heart has time to recover. When therapy fails to reduce BNP, it suggests that the treatments are not addressing the fundamental problem, whether due to inadequate medication doses, irreversible cardiac damage, or ongoing processes driving the disease.

Some centers now use BNP-guided therapy, where medication doses are adjusted specifically to achieve target BNP levels rather than simply treating symptoms. While this approach remains controversial and is not universally adopted, it underscores how closely BNP correlates with cardiac status and outcomes.

When to seek immediate medical attention

While elevated BNP on routine testing warrants discussion with your doctor, certain situations require more urgent evaluation. Knowing these warning signs could save your life.

Symptoms that demand urgent evaluation

Severe shortness of breath at rest or with minimal activity suggests acute cardiac compromise. If you cannot walk across the room without gasping, if you wake up at night choking for air, or if you must sit upright to breathe comfortably, seek immediate care. These symptoms combined with known elevated BNP suggest possible decompensated heart failure requiring hospitalization.

New or worsening leg swelling accompanied by shortness of breath indicates fluid accumulation that the heart cannot handle. This fluid backup can quickly progress to life-threatening pulmonary edema. Do not wait to see if it improves on its own.

Chest pain or pressure always warrants urgent evaluation regardless of your BNP status. When combined with known cardiac dysfunction, chest discomfort could represent new ischemia, progression of heart failure, or other dangerous conditions.

Lightheadedness, fainting, or near-fainting suggests inadequate blood flow to the brain. The failing heart may not be able to maintain sufficient output. Arrhythmias may be developing. These symptoms require prompt evaluation.

Rapid or irregular heartbeat, especially if new, could indicate atrial fibrillation or other arrhythmias that commonly complicate heart failure. These rhythm problems can worsen cardiac function and increase stroke risk. Early detection and treatment improve outcomes.

Working with your healthcare team

If you have elevated BNP, establishing a relationship with a cardiologist makes sense. These specialists have the expertise to interpret your results in context, order appropriate additional testing, and manage any cardiac conditions that emerge. Your primary care physician may be excellent, but complex cardiac cases benefit from specialized input.

Keep a record of your symptoms and how they change over time. Note what activities trigger shortness of breath. Track your weight daily, since rapid weight gain often reflects fluid retention before symptoms become obvious. This information helps your medical team catch problems early.

Understand your medications and take them as prescribed. Many patients with heart failure feel better and stop their medications, only to experience rapid deterioration. The medications are not just treating symptoms. They are protecting your heart from further damage. Adherence is essential.

Know your numbers. Learn your baseline BNP, blood pressure, heart rate, and weight. Understanding what is normal for you helps recognize when something changes. The platforms at SeekPeptides can help you track and understand various biomarker trends as part of a comprehensive health monitoring approach.

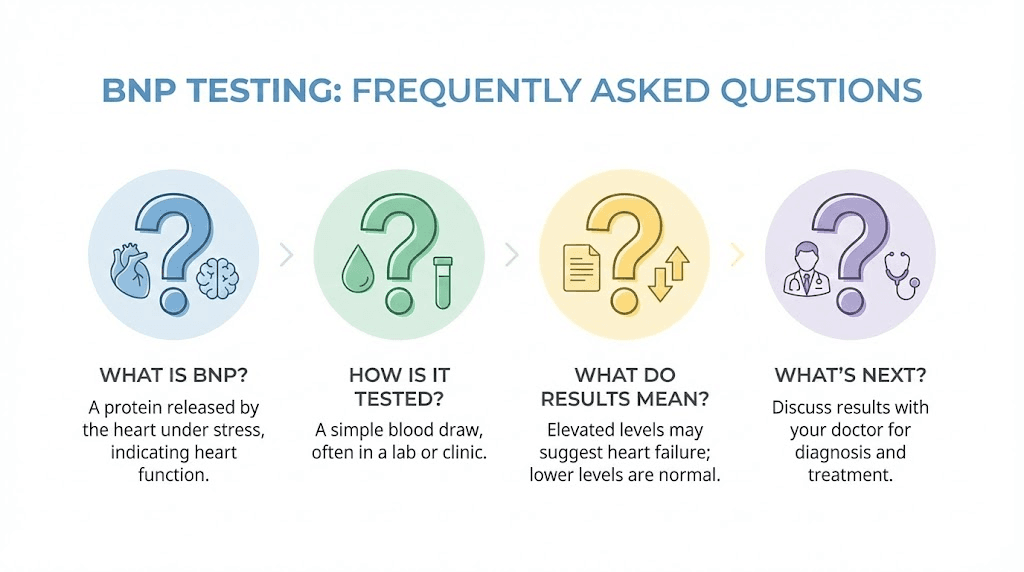

Frequently asked questions

Can high BNP levels return to normal?

Yes. BNP levels can normalize with appropriate treatment of the underlying cause. Patients with heart failure who respond well to medical therapy often see dramatic declines in their BNP over weeks to months. Even those with very high initial readings can sometimes achieve near-normal levels with aggressive management. The key is addressing what is causing the cardiac stress rather than trying to lower BNP directly.

What BNP level is considered dangerous?

BNP levels above 400 pg/mL strongly suggest significant cardiac compromise in symptomatic patients. Levels above 1,000 pg/mL indicate severe cardiac stress with concerning prognosis. Levels above 4,000 pg/mL represent extreme elevation often associated with critical illness. However, danger depends on context. A stable patient with chronic mild elevation requires different management than someone with acute symptoms and rapidly rising levels.

Can stress cause high BNP?

Acute emotional or physical stress can transiently elevate BNP, though usually not to extremely high levels. Severe stress may cause takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also called broken heart syndrome, where the heart temporarily weakens in response to intense emotional distress. This condition can significantly elevate BNP. Chronic stress contributes to hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors that may indirectly raise levels over time.

How often should BNP be checked?

For stable heart failure patients, many cardiologists check BNP every three to six months. During medication adjustments or after hospitalization, more frequent monitoring every few weeks may be appropriate. For patients without known heart disease who had an incidental elevated reading, follow-up testing in one to three months helps determine whether the elevation persists. Your doctor will determine the appropriate schedule based on your individual situation.

Does obesity affect BNP results?

Yes. Obese individuals tend to have lower BNP levels than expected for their cardiac status. The exact mechanism is not fully understood, but adipose tissue appears to clear BNP more rapidly or suppress its production. This means that heart failure in obese patients may be underdiagnosed if doctors rely solely on BNP cutoffs. Some experts suggest using lower thresholds for heart failure diagnosis in obese individuals.

Can BNP be elevated with normal heart function?

Absolutely. Kidney disease, lung conditions, pulmonary embolism, atrial fibrillation, hyperthyroidism, sepsis, and other conditions can all elevate BNP without any impairment in the pumping function of the left ventricle. This is why BNP alone never provides a complete diagnosis. Further testing, including echocardiography, is typically needed to determine the cause of elevation.

What is the difference between BNP and proBNP?

When heart cells produce BNP, they first create a larger precursor called proBNP. This molecule splits into two pieces: active BNP and inactive NT-proBNP. Both pieces circulate in blood and can be measured. NT-proBNP has a longer half-life and higher blood concentrations, making it somewhat easier to measure accurately. The tests are similar but have different reference ranges and cannot be used interchangeably.

Should I worry about mildly elevated BNP?

Mildly elevated BNP, say between 100 and 200 pg/mL, warrants attention but not panic. It may reflect age-related changes, minor kidney dysfunction, or early cardiac remodeling that has not yet caused symptoms. The appropriate response is to discuss the finding with your doctor, undergo any recommended additional testing such as an echocardiogram, and address any modifiable risk factors. Many people with mildly elevated BNP have no significant cardiac disease.

External resources

In case I do not see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night. May your BNP levels stay balanced, your heart stay strong, and your health journey stay informed. Join us.