Jan 5, 2026

The liver's unique biology creates both opportunities and challenges for peptide interventions.

As body's primary detoxification organ processing thousands of compounds daily, liver faces constant oxidative and metabolic stress accumulating damage over decades.

However, exceptional regenerative capacity allows liver recovering from substantial injury (up to 70% liver mass removed regenerates within weeks in healthy individuals), and regenerative peptides potentially amplify this natural healing. Liver's high metabolic activity and blood flow mean peptides administered systemically concentrate in hepatic tissue, though first-pass metabolism also degrades some peptides reducing bioavailability.

Clinical context determines peptide relevance and realistic expectations. Acute liver injury (medication overdose, acute hepatitis, toxin exposure) benefits from immediate hepatoprotective interventions reducing initial damage and supporting rapid regeneration.

Chronic liver disease (fatty liver, alcoholic liver disease, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis) requires sustained protocols addressing ongoing inflammation and fibrosis while supporting remaining hepatocyte function.

Preventive applications (protecting liver during hepatotoxic medication use, supporting detoxification in toxin-exposed individuals, optimizing liver function for metabolic health) use lower-intensity protocols maintaining hepatic resilience. SeekPeptides provides comprehensive resources for liver health peptides tailored to individual situations.

This complete guide covers liver anatomy and physiology understanding peptide targets, specific liver-protective peptides with documented benefits (BPC-157, thymosin alpha-1, epitalon, growth factors), cellular and molecular mechanisms of hepatoprotection, clinical and research evidence for liver peptide applications, practical protocols for different liver conditions (fatty liver, hepatitis, cirrhosis, acute injury), combining peptides with conventional treatments and lifestyle interventions, monitoring liver function and treatment response, safety considerations for liver peptide use, and realistic outcome expectations based on disease severity and peptide mechanisms. SeekPeptides serves as trusted resource for evidence-based hepatoprotective peptide therapy guidance.

Liver anatomy and physiology: Understanding peptide targets

Liver's complex architecture and diverse functions create multiple intervention points for peptides.

Hepatocyte structure and function

Primary liver cells: Hepatocytes constitute 70-80% of liver mass performing most hepatic functions. Synthesize proteins (albumin, clotting factors, transport proteins), metabolize carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, produce bile for fat digestion, detoxify drugs and toxins, store vitamins and minerals. Damage to hepatocytes impairs all these critical functions.

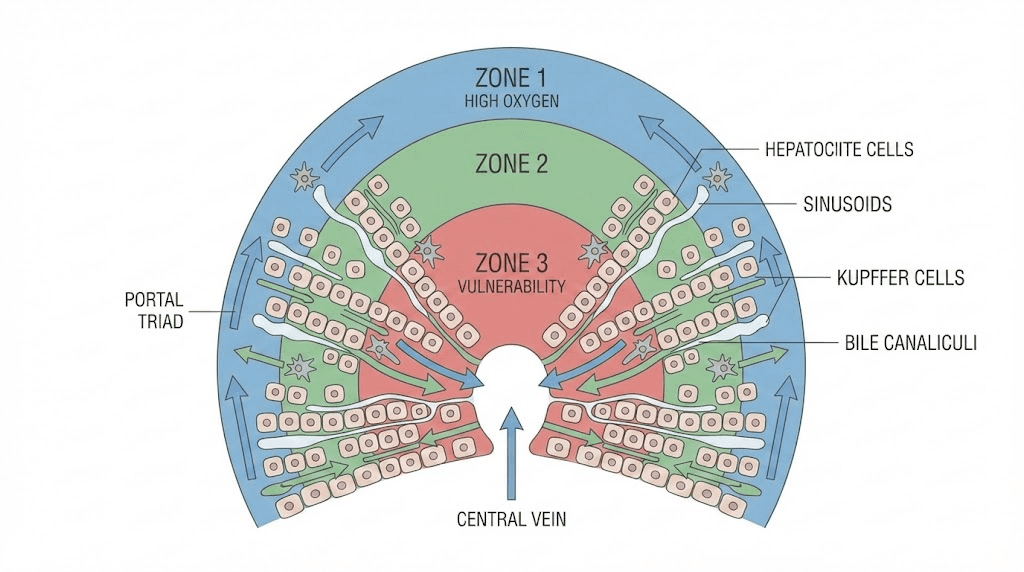

Metabolic zonation: Liver divided into functional zones based on oxygen and nutrient gradients. Zone 1 (periportal, near blood inflow) handles oxidative metabolism, gluconeogenesis, beta-oxidation. Zone 3 (pericentral, near venous outflow) performs glycolysis, lipogenesis, drug metabolism. Zone 3 more susceptible to hypoxic and toxic injury due to lower oxygen tension. Peptides protecting zone 3 hepatocytes particularly valuable for toxin-related liver damage.

Regenerative capacity: Hepatocytes can dedifferentiate and proliferate replacing lost liver mass. Growth factors (HGF, EGF, TGF-alpha) drive this regeneration. Peptides modulating growth factor signaling potentially enhance regenerative responses. However, chronic injury creates fibrotic scarring interfering with regeneration eventually leading to cirrhosis where regeneration severely impaired.

Kupffer cells and immune function

Resident macrophages: Kupffer cells are specialized macrophages residing in liver sinusoids. Clear bacteria, endotoxins, cellular debris from portal blood flowing from intestines. Also produce inflammatory mediators (cytokines, reactive oxygen species) which can damage hepatocytes if excessive. Balance between protective clearance and harmful inflammation critical.

Inflammatory modulation: Chronic Kupffer cell activation drives liver inflammation in alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and other conditions. Anti-inflammatory peptides reducing Kupffer cell activation potentially slow disease progression. Thymosin alpha-1 modulates immune responses making it interesting for liver inflammation conditions.

Fibrosis role: Activated Kupffer cells release factors stimulating hepatic stellate cells (fibroblast-like cells producing collagen) leading to liver fibrosis. Breaking this inflammatory-fibrotic cycle critical for preventing cirrhosis. Peptides interrupting Kupffer-stellate cell signaling potentially therapeutic though specific peptides targeting this pathway still research stage.

Sinusoidal endothelial cells and blood flow

Specialized vasculature: Liver sinusoids have fenestrated (porous) endothelium allowing plasma (but not blood cells) accessing hepatocytes facilitating metabolic exchange. Maintains low pressure despite high blood flow (25% of cardiac output). Sinusoidal dysfunction (loss of fenestrations, increased resistance) contributes to portal hypertension in cirrhosis.

Endothelial health: Maintaining sinusoidal endothelial health preserves liver perfusion and metabolic efficiency. BPC-157 demonstrates vascular protective effects in various tissues potentially extending to liver vasculature. Improved sinusoidal function could enhance hepatocyte oxygenation and nutrient delivery.

Bile production and secretion

Bile acid metabolism: Hepatocytes synthesize bile acids from cholesterol, conjugate them, and secrete into bile canaliculi (small channels between hepatocytes). Bile flows to gallbladder for storage then intestines for fat digestion. Disrupted bile flow (cholestasis) causes bile acid accumulation in liver creating toxicity.

Cholestatic injury: Certain medications, pregnancy, genetic conditions cause cholestasis. Accumulated bile acids damage hepatocyte membranes and mitochondria. Peptides protecting against bile acid toxicity or promoting bile flow potentially therapeutic for cholestatic conditions though specific peptides less researched than those for alcoholic or viral liver disease.

Detoxification systems

Phase I metabolism: Cytochrome P450 enzymes oxidize, reduce, or hydrolyze toxins and drugs creating more water-soluble intermediate metabolites. However, some intermediates more toxic than original compounds (bioactivation) creating oxidative stress and hepatocyte damage. Acetaminophen overdose classic example, creating toxic intermediate overwhelming liver defenses causing acute liver failure.

Phase II metabolism: Conjugation enzymes (glutathione S-transferase, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, sulfotransferases) attach water-soluble groups to phase I metabolites enabling elimination through bile or urine. Adequate glutathione and other conjugation substrates essential. Nutritional support and peptides supporting glutathione synthesis protect against toxicity.

Antioxidant defenses: Superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase detoxify reactive oxygen species generated during metabolism. Antioxidant peptides like certain thymosin variants upregulate these enzymes protecting hepatocytes from oxidative damage accumulating during chronic disease or toxin exposure.

Specific liver-protective peptides

Different peptides target distinct aspects of liver pathology and function.

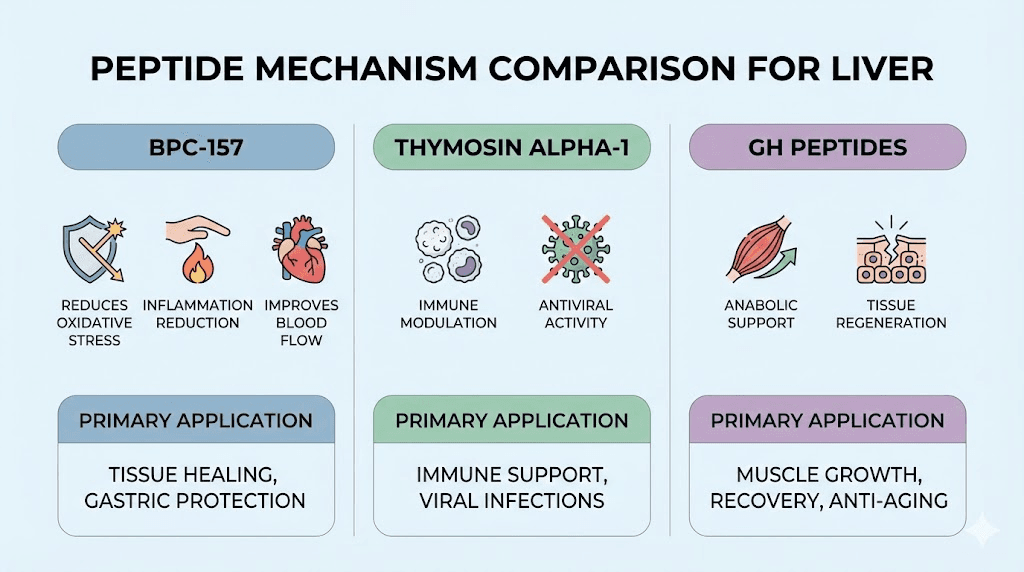

BPC-157: Multi-mechanism hepatoprotection

Alcohol-induced liver damage: Animal studies show BPC-157 protecting against alcohol-induced liver injury. Mechanisms include reducing lipid peroxidation (oxidative damage to cell membranes), decreasing inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL-6), maintaining glutathione levels (primary antioxidant), improving liver blood flow. Rats given alcohol plus BPC-157 show less steatosis (fat accumulation), lower liver enzyme elevations, and better preserved liver architecture versus alcohol alone.

Drug-induced hepatotoxicity: BPC-157 demonstrates protection against various hepatotoxic drugs in research models. Acetaminophen overdose studies show reduced liver necrosis, lower AST/ALT elevations, improved survival with BPC-157 treatment. NSAIDs, chemotherapy agents, antibiotics all create potential liver toxicity where BPC-157 shows protective effects in animal research.

Growth factor modulation: BPC-157 increases VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and other growth factors potentially improving liver regeneration and vascular health. Enhanced angiogenesis supports tissue repair following injury. Growth factor signaling also stimulates hepatocyte proliferation accelerating regeneration.

Practical dosing: Research uses 10mcg/kg in animal studies translating to approximately 200-500mcg daily for humans using standard allometric scaling. Protocols typically 4-8 weeks for acute protection, longer for chronic liver support. Injectable administration (subcutaneous or intramuscular) standard though some research uses oral BPC-157 which may have direct GI protective effects plus systemic absorption. BPC-157 dosing guide provides detailed protocols.

Thymosin alpha-1: Immune modulation and antiviral effects

Hepatitis B and C treatment: Thymosin alpha-1 studied as adjunct therapy for chronic viral hepatitis. Enhances T-cell and natural killer cell function improving antiviral immunity. Clinical trials show improved viral clearance rates and liver function when combined with interferon or other antivirals compared to antivirals alone. FDA-approved in some countries for hepatitis though not in US.

Immune balance: Chronic liver disease involves dysregulated immunity with inadequate antiviral responses yet excessive inflammatory damage. Thymosin alpha-1 helps restore balance, enhancing protective immunity while potentially reducing pathological inflammation. Particularly relevant for viral hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis.

Dosing and administration: Clinical studies typically use 1.6mg subcutaneous injection twice weekly. Protocols run 6-12 months for chronic hepatitis reflecting need for sustained immune modulation. Expensive compared to some peptides ($200-$500+ monthly) but potentially valuable for appropriate indications.

Evidence quality: Thymosin alpha-1 has actual human clinical trial data for liver applications unlike most peptides limited to animal research. Meta-analyses show modest but significant benefits for viral hepatitis. However, recent direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C dramatically changed treatment landscape, thymosin alpha-1 role now primarily hepatitis B or special cases where standard treatments inadequate.

Epitalon and telomerase effects

Cellular aging: Epitalon (also called Epithalamin) claimed to activate telomerase enzyme maintaining telomere length. Telomeres shorten with cell division limiting replicative lifespan. Hepatocytes divide during regeneration potentially exhausting replicative capacity in chronic disease. Telomerase activation theoretically maintains regenerative potential.

Limited liver-specific research: While epitalon studied for general longevity and age-related conditions, specific liver health research minimal. Mechanisms (telomerase activation, antioxidant effects, pineal gland regulation) plausibly benefit liver though direct evidence lacking. More experimental choice than established liver peptide.

Dosing: Typical protocols 5-10mg daily for 10-20 days, repeated 2-4 times yearly. Short treatment cycles characteristic of epitalon use versus continuous administration of other peptides. Relatively inexpensive ($50-$150 per cycle).

Growth hormone and IGF-1 peptides

Anabolic support: Growth hormone peptides (Ipamorelin, CJC-1295, MK-677) increase GH and IGF-1 providing anabolic signals supporting tissue regeneration including liver. However, effects indirect (systemic GH/IGF-1 elevation) versus direct hepatoprotection.

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF): Not peptide itself but growth factor critical for liver regeneration. Some peptides may modulate HGF signaling indirectly. Direct recombinant HGF pharmaceutical development attempted though clinical translation challenges limited success. Understanding growth factor mechanisms informs liver regeneration strategies.

Practical considerations: GH peptides better suited for general metabolic health and body composition than specific liver disease treatment. However, supporting overall anabolic state and metabolic health benefits liver indirectly. Appropriate for preventive liver health or adjunct support rather than primary hepatoprotective intervention.

Glutathione and NAC (not peptides but relevant)

Tripeptide structure: Glutathione (gamma-glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine) technically tripeptide though usually classified as antioxidant rather than therapeutic peptide. Essential for liver detoxification conjugating toxins for elimination. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) provides cysteine building glutathione synthesis.

Acetaminophen overdose: NAC standard medical treatment for acetaminophen poisoning replenishing glutathione stores allowing detoxification of toxic metabolite. Dramatic effectiveness (prevents liver failure if given early) demonstrates glutathione system importance for liver protection.

General liver support: Oral NAC (600-1200mg daily) or IV glutathione potentially supports liver function through enhanced detoxification capacity and antioxidant protection. While not experimental peptide like BPC-157, glutathione support represents evidence-based complement to peptide protocols. Glutathione supplementation enhances liver resilience.

Cellular and molecular mechanisms of hepatoprotection

Understanding how peptides work at cellular level optimizes protocol design and outcome expectations.

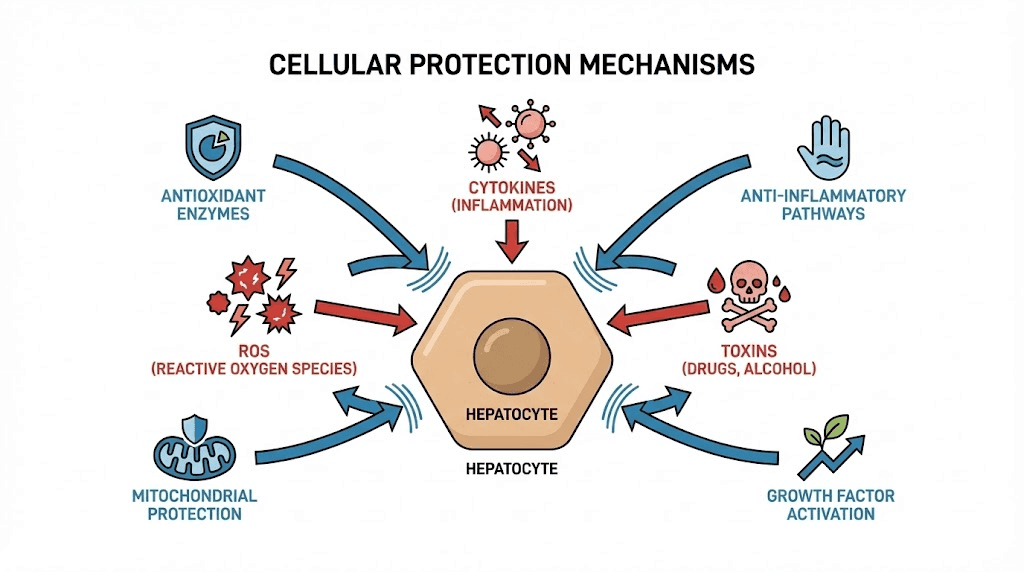

Oxidative stress reduction

ROS generation sources: Alcohol metabolism via alcohol dehydrogenase and CYP2E1 produces acetaldehyde and reactive oxygen species damaging hepatocytes. Drug metabolism, mitochondrial respiration, inflammatory cell activation all generate ROS. Accumulated oxidative damage causes lipid peroxidation (membrane destruction), protein oxidation (enzyme inactivation), DNA damage (mutation and cell death).

Antioxidant enzyme upregulation: Some peptides increase superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase expression providing enhanced antioxidant defense. Mechanism involves transcription factor activation (Nrf2 pathway) inducing antioxidant gene expression. BPC-157 shows evidence of antioxidant enzyme upregulation in various tissues potentially including liver.

Direct ROS scavenging: Some peptides directly neutralize free radicals though generally less potent than dedicated antioxidants (vitamin C, vitamin E, glutathione). Combined direct scavenging and enzyme upregulation creates multi-level protection particularly valuable for chronic oxidative stress conditions.

Mitochondrial protection: Mitochondria both generate and suffer from ROS. Protecting mitochondrial function maintains ATP production (hepatocytes metabolically demanding requiring abundant energy) and reduces ROS leak from dysfunctional electron transport chains. Peptides preserving mitochondrial membrane potential and function protect hepatocytes from energy failure and oxidative injury.

Inflammation modulation

Cytokine regulation: Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, IL-6) produced by Kupffer cells and infiltrating immune cells damage hepatocytes and activate stellate cells promoting fibrosis. Anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-beta in appropriate contexts) support healing and inflammation resolution. Peptides shifting cytokine balance reduce ongoing liver damage.

NF-kappaB pathway: Nuclear factor kappa B master transcription factor regulating inflammatory gene expression. Normally sequestered in cytoplasm, stress or injury triggers nuclear translocation activating hundreds of inflammatory genes. BPC-157 and other peptides inhibit NF-kappaB activation preventing inflammatory cascade initiation. Broad anti-inflammatory effect protects multiple cell types simultaneously.

Kupffer cell modulation: Reducing Kupffer cell activation decreases inflammatory mediator release while maintaining beneficial clearance functions. Thymosin alpha-1 and similar immune modulators potentially achieve this balance versus broad immunosuppression (corticosteroids) which impairs both harmful and protective immune functions.

Resolution vs suppression: Ideal anti-inflammatory approach promotes active resolution (specialized pro-resolving mediators, M2 macrophage polarization, debris clearance, tissue repair) rather than simple suppression. Peptides supporting resolution potentially superior to conventional anti-inflammatories that merely block inflammation without facilitating healing transition.

Hepatocyte proliferation and regeneration

Growth factor signaling: Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-alpha) bind receptors triggering PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways driving cell proliferation. BPC-157 potentially enhances growth factor availability or receptor responsiveness supporting regeneration.

Cell cycle progression: Quiescent hepatocytes must reenter cell cycle (G0 to G1 transition) then progress through S phase (DNA synthesis) and mitosis. Growth signals activate cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases driving cell cycle. Peptides facilitating cell cycle entry and progression accelerate regeneration following acute injury.

Stem and progenitor cells: Liver contains hepatic progenitor cells (oval cells) activated when massive hepatocyte loss overwhelms regenerative capacity or chronic injury impairs hepatocyte proliferation. These progenitors differentiate into hepatocytes or cholangiocytes (bile duct cells). Peptides supporting progenitor cell activation and differentiation potentially valuable for severe liver disease.

Limitations: Cirrhotic liver with extensive fibrosis shows impaired regeneration regardless of growth signals. Scar tissue physically prevents hepatocyte expansion and disrupts signaling. Peptides enhance regeneration in liver capable of responding but cannot overcome complete cirrhotic transformation. Realistic expectations account for disease stage.

Fibrosis prevention and reversal

Stellate cell activation: Hepatic stellate cells normally store vitamin A remaining quiescent. Chronic injury causes activation transforming into myofibroblasts producing collagen (types I and III creating scar tissue). Activated stellate cells also proliferate and resist apoptosis perpetuating fibrosis even after initial injury resolved.

TGF-beta paradox: Transforming growth factor beta promotes fibrosis through stellate cell activation but also regulates inflammation and supports certain aspects of healing. Simply blocking TGF-beta potentially harmful. Nuanced modulation ideal though difficult to achieve. Most peptides don't specifically target fibrosis pathways, addressing inflammation and oxidative stress indirectly reduces stellate activation.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs): Enzymes degrading collagen and other matrix proteins. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) regulate MMP activity. Fibrosis reflects imbalance (excessive collagen production, inadequate degradation, or both). Some evidence peptides modulate MMP/TIMP ratios promoting matrix remodeling though liver fibrosis research limited.

Reversal potential: Early fibrosis potentially reversible with successful treatment of underlying cause and supportive interventions. Advanced cirrhosis largely irreversible with current therapies. Peptides potentially slow progression or modestly reverse early fibrosis but cannot cure cirrhosis. Anti-fibrotic drugs (in development) show promise though none FDA-approved for liver fibrosis specifically yet.

Bile acid and cholestasis management

Bile acid toxicity: Hydrophobic bile acids (chenodeoxycholic acid, lithocholic acid, deoxycholic acid) damage membranes causing apoptosis and necrosis. Cholestasis causes accumulation creating hepatotoxicity. UDCA (ursodeoxycholic acid) hydrophilic bile acid used clinically to displace toxic bile acids.

Peptide effects: Limited research on peptides specifically for cholestatic liver disease. However, general hepatoprotective effects (antioxidant, anti-inflammatory) potentially beneficial. BPC-157 shown protecting against various liver injuries possibly including cholestasis though specific research lacking.

Bile flow promotion: Some traditional liver herbs (milk thistle, artichoke) claimed to promote bile flow (choleretic effects). Whether peptides possess similar properties unknown. Bile acid metabolism and secretion complex, specific peptide effects require direct investigation.

Clinical and research evidence

Examining human and animal data establishes realistic expectations for liver peptide applications.

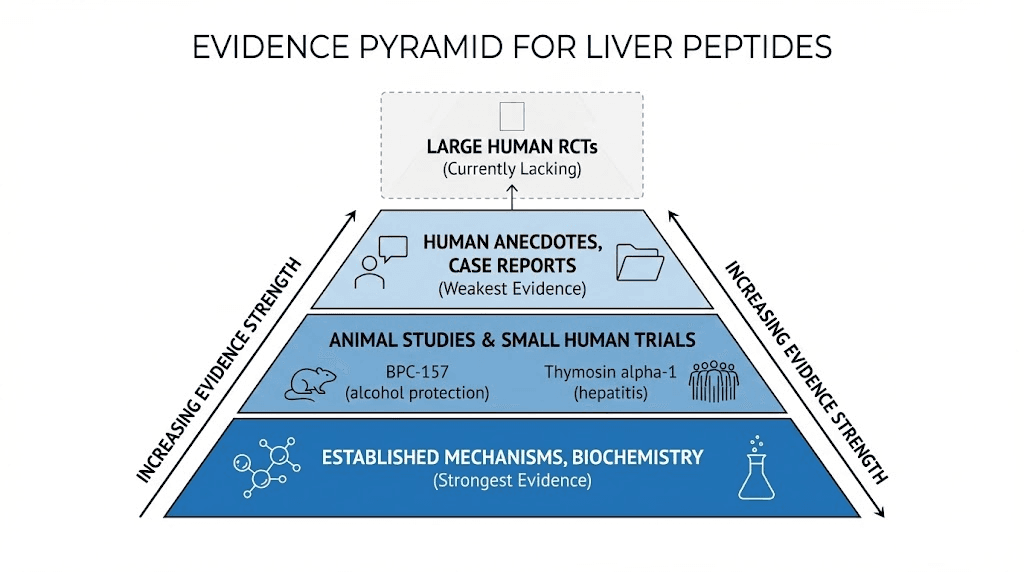

Animal model research

BPC-157 alcohol studies: Rats given alcohol to induce liver damage then treated with BPC-157 show dose-dependent protection. Lower doses (10mcg/kg) show modest benefits while higher doses (10-40mcg/kg) demonstrate substantial reduction in liver enzyme elevations, decreased fat accumulation, preserved liver architecture histologically. Multiple independent studies confirm hepatoprotective effects.

Drug toxicity models: Acetaminophen overdose, carbon tetrachloride poisoning, other hepatotoxin models used to study liver injury. BPC-157 reduces mortality, decreases liver necrosis extent, lowers transaminase elevations. Protective mechanisms include antioxidant effects, maintained glutathione, improved liver blood flow, reduced inflammation.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury: Liver transplantation or liver surgery with vascular clamping creates ischemia (oxygen deprivation) followed by reperfusion (oxygen return) causing oxidative burst and inflammation. BPC-157 shown protecting against ischemia-reperfusion injury in animal models suggesting potential perioperative applications.

Limitations: Animal models use young healthy rodents, controlled injury timing and severity, much higher body weight-adjusted doses than typical human use. Results demonstrate biological plausibility and mechanisms but cannot guarantee human efficacy or safety. Human trials needed for definitive evidence.

Human clinical data

Thymosin alpha-1 hepatitis trials: Multiple small to moderate clinical trials (50-200 patients) testing thymosin alpha-1 for chronic hepatitis B. Results show improved ALT normalization, increased HBeAg seroconversion (marker of reduced viral activity), better sustained virologic response when combined with interferon. Meta-analyses confirm modest but significant benefits. However, newer direct-acting antivirals often preferred currently.

Hepatitis C studies: Thymosin alpha-1 studied as interferon adjunct before direct-acting antivirals revolutionized hepatitis C treatment. Showed benefits in difficult-to-treat patients (genotype 1, non-responders to standard therapy). Now primarily historical interest given highly effective DAA regimens (sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, others) achieving 95%+ cure rates.

Lack of BPC-157 human trials: Despite robust animal data, no published randomized controlled trials testing BPC-157 for liver disease in humans. Anecdotal reports and case series suggest potential benefits though without controlled conditions impossible distinguishing peptide effects from natural healing, placebo responses, or concurrent treatments.

Safety data from widespread use: Thousands of individuals use BPC-157 for various conditions (not just liver) providing real-world safety data. Serious adverse events extremely rare suggesting favorable safety profile. However, long-term effects (years to decades) and rare complications remain unknown without systematic surveillance.

Human observational evidence

Self-experimentation reports: Online communities (Reddit, forums) include individuals using liver peptides for fatty liver, alcohol-related liver injury, or general liver support. Common themes include normalized liver enzymes, improved energy, reduced symptoms though objective liver imaging or biopsy rarely performed. Confirmation bias, placebo effects, concurrent lifestyle changes confound interpretation.

Integrative medicine practitioners: Some clinics offer peptide therapy including liver support protocols. Report generally positive outcomes though publication bias (successful cases more likely reported), lack of controls, and concurrent interventions (nutrition counseling, supplements, lifestyle modification) prevent attributing improvements specifically to peptides.

Need for rigorous research: Current human evidence insufficient for definitive efficacy claims. Well-designed trials needed comparing peptides to placebo and standard treatments with objective endpoints (liver histology, fibrosis markers, long-term complications). Until such research completed, liver peptide use remains experimental supported by animal data and mechanistic plausibility.

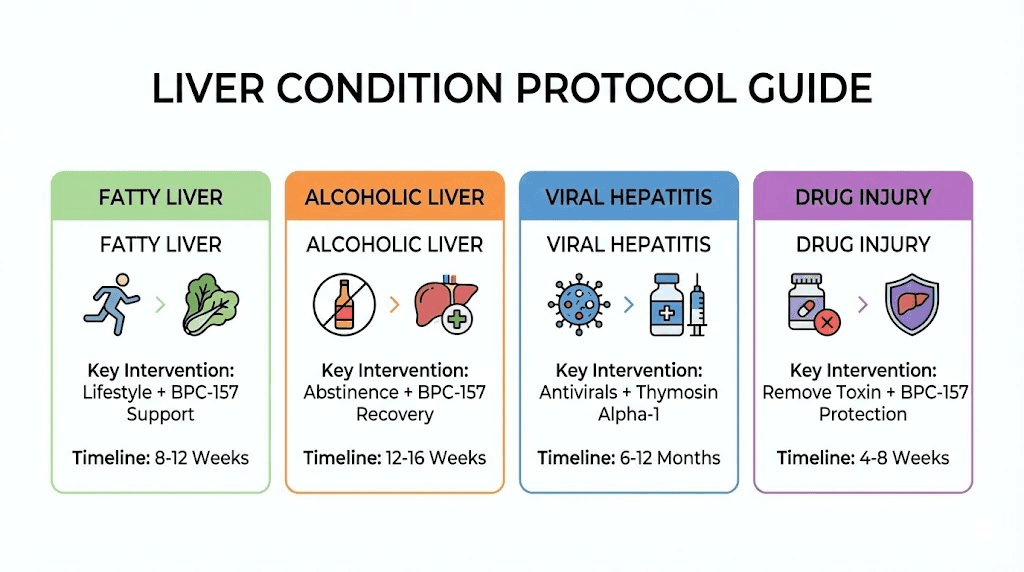

Practical protocols for liver conditions

Tailoring peptide use to specific hepatic pathologies optimizes outcomes.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD/NASH)

Condition overview: Fat accumulation in liver (steatosis) occurring without significant alcohol consumption. Simple steatosis generally benign while non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) involves inflammation and fibrosis potentially progressing to cirrhosis. Closely linked to metabolic syndrome (obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension).

Peptide approach: BPC-157 200-500mcg daily for 8-12 weeks minimum. Focus on anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects reducing hepatocyte stress. Growth hormone peptides (Ipamorelin + CJC-1295) potentially beneficial through improving insulin sensitivity and body composition indirectly benefiting liver. However, lifestyle modification (weight loss, exercise, nutrition) remains primary treatment, peptides adjunctive support.

Monitoring: Baseline and follow-up liver enzymes (AST, ALT), metabolic panel (glucose, lipids), liver ultrasound or elastography (measuring stiffness indicating fibrosis). Successful protocols show enzyme normalization, reduced liver fat on imaging, improved metabolic markers. However, changes require months given chronic nature.

Realistic expectations: Peptides unlikely reversing NASH without concurrent weight loss and metabolic improvement. May accelerate healing and reduce inflammation supporting lifestyle interventions. Substantial liver fat reduction requires significant weight loss (7-10% body weight minimum) which peptides alone cannot achieve.

Alcoholic liver disease

Spectrum of disease: Ranges from simple steatosis to alcoholic hepatitis (severe acute inflammation potentially fatal) to cirrhosis. Abstinence essential for healing regardless of other interventions. Continued drinking overwhelms any hepatoprotective measures.

Acute protection: For those unable or unwilling to abstain completely, BPC-157 during drinking periods potentially reduces acute damage though not eliminating risk. Research doses 200-500mcg daily. However, cannot ethically recommend peptides as "protection" enabling continued harmful drinking. Abstinence always preferable.

Recovery support: After ceasing alcohol, peptides potentially accelerate liver recovery. BPC-157 400-500mcg daily for 12-16 weeks supporting regeneration and reducing residual inflammation. Thymosin peptides potentially beneficial given immune dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Combine with nutritional support (thiamine, folate, protein, multivitamin).

Medical supervision essential: Alcoholic hepatitis requires medical care (corticosteroids potentially indicated, treating complications like ascites and encephalopathy). Cirrhosis complications (variceal bleeding, infections, liver cancer) need specialized management. Peptides adjunctive, never replacing necessary medical treatment. SeekPeptides emphasizes medical collaboration for serious conditions.

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis B: Thymosin alpha-1 1.6mg twice weekly for 6-12 months potentially beneficial especially combined with antiviral medications (entecavir, tenofovir). Improves immune responses against virus. However, modern antivirals highly effective, thymosin primarily adjunct or special cases (immunocompromised patients, antiviral non-responders).

Hepatitis C: Direct-acting antivirals cure rate 95%+ making adjunctive therapies less relevant. Historically, thymosin alpha-1 used with interferon though interferon-based regimens obsolete currently. Post-treatment, general liver support (BPC-157, antioxidants) potentially beneficial for residual inflammation or fibrosis.

Prevention of progression: Even with viral suppression or cure, liver fibrosis may persist. Ongoing peptide support (BPC-157, antioxidants) theoretically reduces fibrosis progression risk though lacks direct evidence. Benefits uncertain but low downside if peptides well-tolerated and affordable.

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI)

High-risk medications: Acetaminophen overdose, certain antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate, isoniazid), statins, chemotherapy, anabolic steroids, herbal supplements, many others cause liver injury. Severity ranges from mild enzyme elevations to acute liver failure.

Immediate response: Discontinue offending agent if possible. N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen. Medical evaluation for severe elevations. BPC-157 potentially protective given animal data though no human evidence. Could reasonably add 400-500mcg daily during recovery though standard care takes priority.

Preventive use: For those requiring known hepatotoxic medications long-term (chemotherapy, isoniazid TB treatment, others), prophylactic peptides theoretically protective. However, limited evidence supporting this approach. Would need balancing potential benefits against intervention costs and complexity. Discuss with prescribing physician before adding peptides to medication regimen.

Cirrhosis and advanced liver disease

Limitations: Cirrhosis represents end-stage liver disease with extensive scarring, limited regenerative capacity, portal hypertension, and high complication risk. Peptides cannot reverse established cirrhosis or substitute for liver transplantation when indicated. Realistic expectations critical.

Supportive role: May slow progression, support remaining hepatocyte function, reduce complications. BPC-157 200-400mcg daily long-term potentially beneficial though evidence lacking. Thimosin alpha-1 for immune support if recurrent infections (common in cirrhosis). Growth hormone peptides for maintaining muscle mass (sarcopenia common and prognostically important in cirrhosis).

Medical management priority: Cirrhosis requires specialist care (hepatologist). Managing varices, ascites, encephalopathy, screening for liver cancer, assessing transplant candidacy all essential. Peptides strictly adjunctive, never primary treatment or transplant alternative. Advanced disease considerations guide appropriate use.

Perioperative liver support

Liver surgery and transplantation: Major liver resection or transplantation creates ischemia-reperfusion injury and regenerative demands. BPC-157 shown protective in animal models. Could reasonably use perioperatively (starting 1-2 weeks before surgery, continuing 8-12 weeks after) supporting healing though discuss with surgical team.

Dosing: 400-500mcg daily given magnitude of surgical stress. Higher than typical maintenance dosing reflects acute protection and healing needs. Combine with nutritional optimization (protein, vitamins, minerals).

Safety considerations: Inform anesthesiologist and surgeon about all peptide use. While BPC-157 safety profile excellent, full disclosure supports optimal perioperative care. Potential concerns about bleeding (theoretical given vascular effects) though no evidence of actual increased bleeding risk.

Combining peptides with conventional treatments

Integration strategies maximize outcomes while respecting medical standards.

Peptides with prescription medications

Antiviral drugs: Hepatitis B antivirals (entecavir, tenofovir) or hepatitis C direct-acting antivirals (sofosbuvir-based regimens) represent primary treatment. Thymosin alpha-1 potentially enhances response though modern antivirals sufficiently effective that adjuncts often unnecessary. Adding peptides requires physician discussion, no known dangerous interactions but coordination important.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA): Used for primary biliary cholangitis and other cholestatic conditions. No interactions expected with peptides. Combining UDCA with BPC-157 theoretically synergistic (UDCA addresses bile acid toxicity, BPC-157 provides general hepatoprotection) though no research confirming additive benefits.

Corticosteroids: Severe alcoholic hepatitis sometimes treated with prednisolone. Corticosteroids broadly immunosuppressive while thymosin alpha-1 immune-enhancing creating theoretical conflict. However, immunosuppression for acute crisis while peptides for chronic support potentially compatible in different disease phases.

Diabetes medications: Metformin and other diabetes drugs important for metabolic control reducing NAFLD. GH peptides affect insulin sensitivity (potential insulin resistance with high-dose or prolonged use) requiring monitoring. However, therapeutic GH peptide doses generally tolerable. Blood glucose monitoring guides safety.

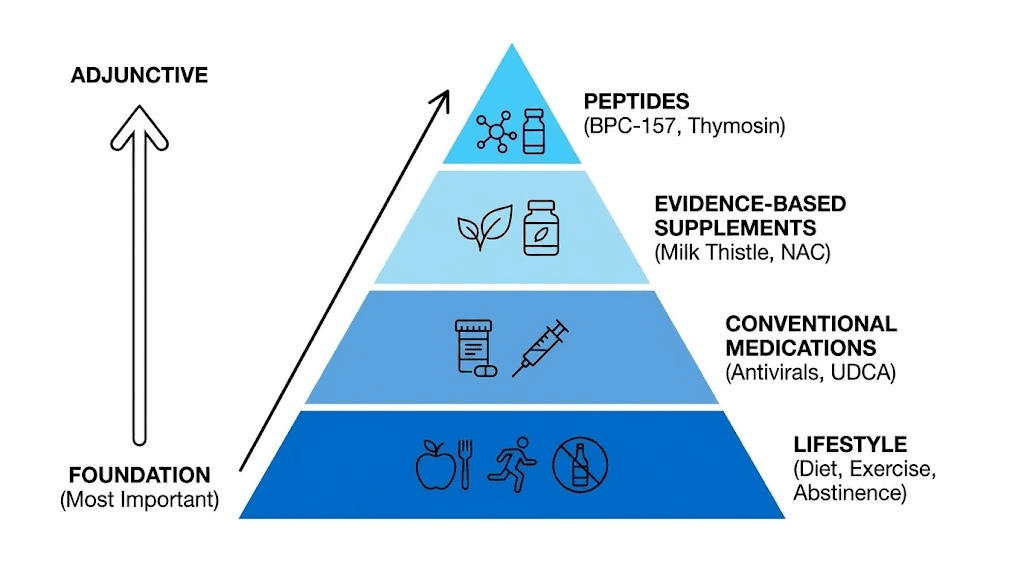

Lifestyle interventions priority

Weight loss for NAFLD: 7-10% body weight reduction dramatically improves liver fat, inflammation, and fibrosis in NAFLD/NASH. More effective than any medication or peptide. Lifestyle modification (calorie restriction, exercise, behavior change) remains primary intervention. Peptides support but never replace necessary lifestyle changes.

Alcohol abstinence: Absolutely required for alcoholic liver disease. No peptide or medication allows safe continued drinking with advanced alcoholic liver disease. Complete abstinence potentially allows substantial recovery even from severe disease. Relapse prevents healing regardless of other interventions.

Exercise benefits: Regular physical activity improves insulin sensitivity, reduces liver fat, decreases inflammation, supports muscle mass. Combines synergistically with peptides. Sedentary individuals starting exercise plus peptides likely attribute all benefits to peptides when exercise contributing substantially or predominantly.

Nutritional optimization: Adequate protein (preventing sarcopenia), limited processed foods and added sugars, abundant vegetables and fruits (providing antioxidants and fiber), adequate hydration all support liver health. Nutrition and peptides work synergistically for optimal outcomes.

Supplement integration

Milk thistle (silymarin): Popular liver supplement with moderate evidence for liver protection. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects similar to peptides though different mechanisms. Combining potentially synergistic. Typical dose 140-280mg silymarin 2-3 times daily. Well-tolerated, inexpensive ($10-$20 monthly).

N-acetylcysteine (NAC): Precursor to glutathione supporting detoxification. Evidence-based for acetaminophen overdose, potential benefits for general liver health. 600-1200mg daily typical supplementation. Excellent safety profile. Logical combination with peptides given complementary mechanisms (NAC provides substrate, peptides provide signaling).

Alpha-lipoic acid: Antioxidant supporting mitochondrial function and glucose metabolism. Studies in diabetic neuropathy, potential benefits for NAFLD. 300-600mg daily. Combines well with peptides though adds cost ($20-$40 monthly for quality product).

Vitamin E and omega-3 fatty acids: NASH clinical trial showed vitamin E (800 IU daily) improving liver histology. Omega-3s (2-4g EPA+DHA daily) reduce inflammation and liver fat. Evidence-based additions to liver support protocols. Vitamin E cautions for certain populations (increased bleeding risk, prostate cancer concerns in some studies).

Avoiding hepatotoxic substances: Alcohol obviously, but also excessive acetaminophen, certain herbs and supplements (kava, comfrey, ephedra, high-dose vitamin A), unnecessary medications. Minimizing liver stress allows peptides and liver's natural healing mechanisms working optimally. Hepatotoxin avoidance essential foundation.

Monitoring and medical coordination

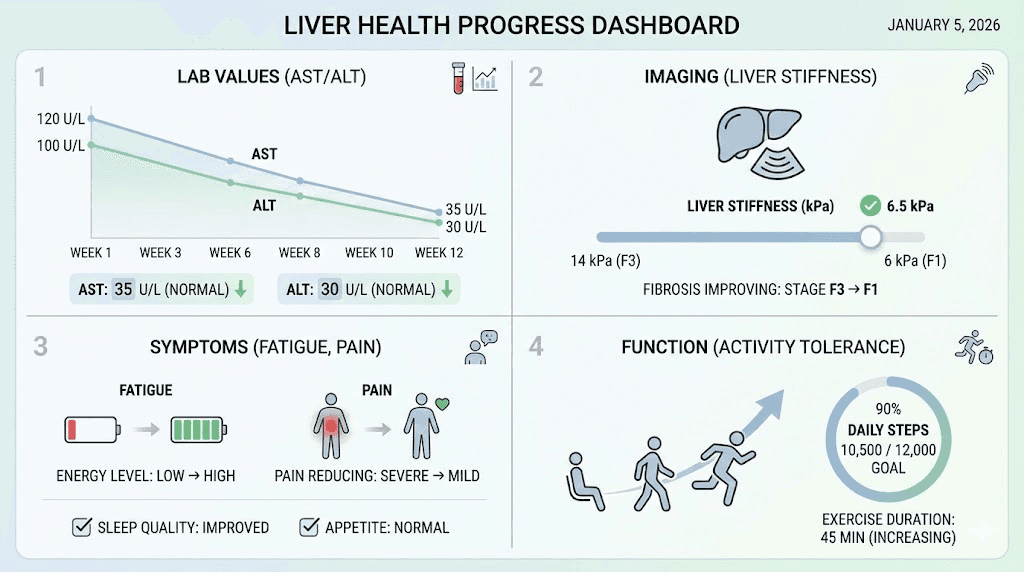

Baseline assessment: Before starting peptides for liver health, establish baseline through physician evaluation. Liver enzymes (AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, GGT), bilirubin, albumin, coagulation studies, complete blood count, metabolic panel. Imaging if indicated (ultrasound, CT, MRI). Understand starting point and disease severity.

Follow-up testing: Recheck liver enzymes every 4-8 weeks initially monitoring response. Improving or normalizing enzymes suggest beneficial effects. Worsening despite peptides indicates ineffective intervention or disease progression requiring medical escalation. Stable enzymes may reflect disease stabilization (positive) or peptides not providing additional benefit beyond natural course.

Physician communication: Inform hepatologist or primary care provider about peptide use. While many physicians unfamiliar with research peptides or skeptical, full disclosure supports optimal care. Medication interactions, interpretation of lab changes, coordinating monitoring schedules all benefit from physician awareness.

Red flags requiring immediate medical attention: Jaundice (yellowing skin/eyes), confusion or altered mental status (hepatic encephalopathy), severe abdominal pain or swelling, vomiting blood or black stools, fever with liver disease, rapidly worsening symptoms. These indicate serious complications requiring emergency care regardless of peptide protocols.

Monitoring and measuring success

Objective and subjective measures track liver health improvements or identify treatment failures.

Laboratory markers

Transaminases (AST, ALT): Hepatocyte injury releases these enzymes into bloodstream. Elevations indicate active damage. Declining levels suggest reduced injury and healing. ALT more liver-specific than AST (AST also in heart, muscle, other tissues). Target normal range (typically <40 IU/L though some labs use different cutoffs).

Alkaline phosphatase and GGT: Indicate cholestasis (bile flow obstruction) or bile duct disease. Alkaline phosphatase also elevated in bone disease, pregnancy. GGT more specific for liver and sensitive to alcohol. Normalizing GGT in recovering alcoholic positive sign.

Bilirubin: Waste product from red blood cell breakdown, liver processes and excretes in bile. Elevated bilirubin (jaundice) indicates severe liver dysfunction or bile duct obstruction. Mild elevations (1.5-3 mg/dL) concerning, high levels (>3 mg/dL) indicate serious disease. Declining bilirubin during treatment favorable prognostic sign.

Albumin and coagulation: Liver synthesizes albumin (serum protein) and clotting factors. Advanced liver disease shows low albumin and prolonged prothrombin time/INR reflecting impaired synthetic function. Improving albumin and INR indicate better liver function though changes slow (albumin half-life ~20 days).

Metabolic markers: For NAFLD, tracking glucose, HbA1c, lipids (triglycerides, cholesterol), assesses metabolic improvement paralleling liver improvements. Insulin resistance drives NAFLD, improving insulin sensitivity crucial for meaningful liver recovery.

Imaging and non-invasive tests

Ultrasound: Detects fatty liver (echogenicity changes), cirrhosis (nodular appearance, enlarged spleen), masses (liver cancer screening). Serial ultrasounds track changes in liver appearance. However, steatosis quantification imprecise on ultrasound, fibrosis detection limited.

Elastography (FibroScan): Measures liver stiffness correlating with fibrosis. Non-invasive, quick, painless alternative to biopsy for fibrosis staging. Serial measurements track progression or regression. Stiffness decreasing over time indicates improving fibrosis. Limitations include obesity, ascites interfering with measurements.

CT and MRI: More detailed than ultrasound though more expensive. MRI with special sequences (MR elastography) quantifies fat and fibrosis accurately. Typically reserved for unclear diagnoses or research studies rather than routine monitoring. Radiation from CT limits repeated use.

Fibrosis biomarkers: Blood tests (FIB-4, APRI, ELF panel) estimate fibrosis stage using combinations of platelets, transaminases, age, and other factors. Less accurate than imaging or biopsy but convenient and inexpensive. Serial measurements showing improving scores suggest reduced fibrosis though individual test variability limits interpretation.

Clinical symptoms and functional status

Fatigue improvement: Liver disease commonly causes fatigue. Energy levels improving suggests better liver function and overall health though subjective and multifactorial. However, patients often report increased energy as early sign of liver recovery even before objective markers change.

Abdominal comfort: Liver enlargement or inflammation can cause right upper quadrant discomfort. Resolution of pain or fullness indicates reduced liver inflammation or normalization of liver size. However, cirrhotic liver may actually shrink with advanced scarring.

Jaundice resolution: Yellowing skin or eyes from elevated bilirubin. Clearing indicates improved bilirubin processing and excretion. Visible to patient motivating continued treatment adherence.

Functional capacity: Ability to work, exercise, perform daily activities without excessive fatigue. Improving functional status better quality of life indicator than lab values though both important. Ultimately, how patients feel and function matters most for individual wellbeing.

Long-term outcomes

Disease progression prevention: Success defined as stabilization rather than necessarily reversal for advanced disease. Preventing progression from NAFLD to NASH, or NASH to cirrhosis, represents major victory even without complete resolution. Similarly, stable compensated cirrhosis avoiding decompensation (ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding) successful outcome.

Complication avoidance: Liver disease leads to portal hypertension, esophageal varices, hepatocellular carcinoma, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, other serious complications. Years without complications despite ongoing disease indicates successful management even if cure unachieved.

Liver transplant avoidance or delay: For cirrhosis patients, avoiding transplant need represents successful stabilization. Delaying transplant allows time for living donor identification, addressing other health issues, or spontaneous improvement. While some patients ultimately require transplantation despite optimal management, delaying procedure worthwhile.

Quality of life: Maintaining employment, relationships, hobbies, independence despite liver disease. Not always captured by lab tests but critically important for patients. Successful protocols improve or maintain quality of life even if objective measures show persistent abnormalities.

Safety and realistic expectations

Responsible peptide use requires understanding both potential benefits and limitations.

Side effect profiles

BPC-157 safety: Generally excellent tolerance. Injection site reactions (redness, pain, mild swelling) most common. Systemic side effects rare (occasional nausea, fatigue, headache). No serious adverse events documented in widespread use though formal safety studies lacking. Long-term effects (years) unknown. Considered very safe based on available data.

Thymosin alpha-1 side effects: Mild injection site reactions common. Flu-like symptoms possible. Generally well-tolerated in clinical trials. More expensive than BPC-157 ($200-$500+ monthly versus $50-$200 for BPC-157). Cost-benefit assessment important.

Growth hormone peptides: Can cause water retention, joint discomfort, numbness (carpal tunnel-type symptoms), increased appetite. Usually dose-dependent and reversible. Insulin resistance potential concern with prolonged use requiring glucose monitoring. Not specific liver concerns but relevant for those using GH peptides as part of comprehensive liver support.

General peptide precautions: Unknown effects in pregnancy/breastfeeding (avoid), potential cancer concerns theoretical (no evidence but caution warranted), quality variability (testing essential), interactions with medications possible (physician coordination important).

Contraindications and warnings

Active cancer: Liver cancer common complication of cirrhosis. Growth-promoting peptides theoretically could stimulate cancer though no evidence. Extreme caution warranted with known hepatocellular carcinoma, likely avoiding growth factors entirely. Peptides with anti-inflammatory effects without growth promotion potentially safer (thymosin alpha-1).

Acute liver failure: Requires intensive medical care possibly including transplantation. Peptides not substitute for necessary medical management. Could potentially add as adjunctive support but only with medical team coordination, never self-treatment of acute liver failure.

Autoimmune hepatitis: Immune modulating peptides could theoretically affect autoimmune liver disease either beneficially or harmfully. Thymosin alpha-1 studied in some autoimmune contexts. However, requires specialist management, peptides only under physician supervision for autoimmune conditions.

Medication interactions: Most peptides have minimal drug interactions. However, full disclosure to physicians ensures safety especially for people taking multiple medications or immunosuppressants. Coordination prevents potential issues.

What peptides cannot do

Cure cirrhosis: Advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis largely irreversible with current therapies. Peptides may slow progression or modestly improve some parameters but cannot restore normal liver architecture once cirrhosis established. Transplantation only cure for decompensated cirrhosis.

Replace abstinence: No peptide or medication allows safe continued drinking with alcoholic liver disease. Abstinence mandatory. Similarly, NAFLD requires lifestyle modification (weight loss, exercise, nutrition), peptides support but never substitute.

Eliminate medication needs: Viral hepatitis requires antivirals. Autoimmune hepatitis needs immunosuppression. Complications (ascites, encephalopathy, varices) require specific treatments. Peptides adjunctive, not replacing necessary medical care.

Guarantee outcomes: Individual response variability means some people show dramatic improvements while others minimal benefits. Disease severity, concurrent treatments, lifestyle factors, genetics all influence outcomes. No universal success rate for experimental interventions.

How SeekPeptides supports liver health

SeekPeptides provides comprehensive resources for evidence-based liver peptide therapy.

Detailed liver peptide guides covering mechanisms, dosing, monitoring, and integration with conventional care. Condition-specific protocols for fatty liver, hepatitis, cirrhosis, and drug-induced injury.

Research database aggregating animal studies, clinical trials, and case reports. Evidence summaries helping understand what's proven versus theoretical.

Community forums connecting individuals using liver peptides. Sharing experiences, troubleshooting issues, supporting recovery journeys. Collective wisdom complementing scientific evidence.

Vendor verification ensuring quality products for liver applications. Testing results and reliability tracking reducing risks from poor-quality peptides.

Medical coordination guides helping communicate with physicians about peptide use. Supporting productive conversations and integrated care approaches.

Safety monitoring tools for tracking lab results, symptoms, and progress. Templates ensuring comprehensive assessment and early problem detection.

SeekPeptides remains committed to advancing liver peptide therapy through education, community support, and evidence-based guidance.

Helpful resources

In case I don't see you, good afternoon, good evening, and good night.

May your liver stay healthy, your peptides stay effective, and your hepatic function stay optimized.